Back in 2015, the European Resuscitation Council established a maximum of 20min of caldiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) maneuvers for non-shockable rhythms without specifying the time in the case of cardiac arrests (CA) with shockable rhythms.1

The excellent review from López-Messa provides, based on the scarce series available, a wider CPR window, particularly in certain groups of population, and addresses the use of the available diagnostic and therapeutic elements in and out of the hospital (capnography, ultrasound, etc.).2

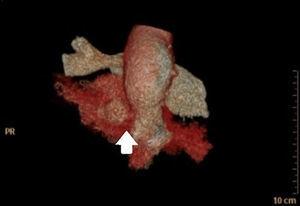

Based on his proposal on CPR times, we hereby present the following case: thirty-nine-year-old male fire fighter without a significant personal history who back in his home suffers a cardiac arrest witnessed by his wife who immediately calls 112. This emergency service explains to her how to perform CPR maneuvers. Then the wife calls a neighbor who happens to be an ER doctor. Using her phone hands-free functionality, this ER physician explains to her how to perform CPR maneuvers and gives her personal support until her arrival. After 20min performing basic CPR maneuvers, the EMT arrives with a SAED capable of identifying shockable rhythms and extends CPR for another 19min with advanced life support plus 3electric discharges. The victim recovers spontaneous circulation, the trace in the ST segment elevation is detected, and the patient is transferred to a hospital with hemodynamic laboratory capabilities, and then admitted to the Intensive Care Unit.

After the hospital discharge and after patient's follow-up for one full year, no neurological or any other kind of sequelae have been identified; the patient has remained asymptomatic and without any new cardiological events (Appendix A additional material).

Our case is similar to the 11 patients from Grunau et al.’s series who went over the 30min-threshold performing CPR maneuvers. Eight (8) of these patients kept their neurological capabilities intact after hospital discharge.3 Similarly, Loma-Osorio's study on out-of-hospital sudden death due to cardiac causes with Coronary Intensive Care Unit admission established a series of negative prognostic factors that we also saw in our patient, such as the need for invasive ventilation for over 10 days, CPR maneuver times <30min, and shock and lactic acidosis upon arrival at the hospital.4 However, our case shares good prognostic factors such as, among others, being a witnessed out-of-hospital sudden death, the implementation of SAED with initial shockable rhythm, the induction of hypothermia, and the ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) as the underlying cause. As the OHSCAR study establishes, we believe that the initial phone support given to the CA witness also contributed to a successful PCR in the aforementioned case.5

As López Mesa,2 at least in the subgroup of young and healthy patients, with a witnessed CA and initial shockable rhythm, we should think about the possibility of extending the time of CPR maneuvers up to 40min, even more so if a STEMI has been the cause leading to the CA.

Please cite this article as: Báez-Ferrer N, Gironés-Bredy C, Domínguez-Rodriguez A, Burillo-Putze G. Aumento del tiempo para cesar la reanimación cardiopulmonar en la parada cardiaca extrahospitalaria. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:395–396.