The main purpose of this study was to analyze the prevalence of do-not-intubate (DNI) orders in patients admitted to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) due to acute respiratory failure (ARF) and who were treated with non-invasive ventilation (NIV). The secondary objective was to correlate the presence of a DNI order with the patient’s prognosis.

DesignRetrospective observational study.

SettingPolyvalent ICU.

PatientsAll consecutively admitted ICU patients for ARF between January 1st, 1997, and December 31st, 2022, who were treated with NIV.

Main variables of interestInitial clinical variables, NIV failure rate, complications, in-hospital and one-year mortality.

Results5972 patients were analyzed, 1275 (21.3%) presenting a DNI order. The mean age was 68.2 ± 14.9; 60.2% were male. The most frequent cause of DNI order was chronic respiratory disease (452 patients; 35.5%). Patients with DNI order were older, had higher Charlson comorbidity index and higher frailty. NIV failure occurred in 536 (42.0%) patients in the DNI order group vs. 1118 (23.8%) in the non-DNI order group (p < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was higher in patients with DNI order (57.9% vs 16.4%; p < 0.001). The adjusted OR for inhospital mortality was 2.14 (95% CI 1.98 to 2.31).

ConclusionsDNI orders are common in patients with ARF treated with NIV and they related to worse short and long-term prognosis.

El objetivo principal del estudio ha sido analizar la prevalencia de la orden de no intubación (ONI) en los pacientes ingresados en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) debido a insuficiencia respiratoria aguda (IRA) y que fueron tratados con ventilación no invasiva (VNI). El objetivo secundario fue relacionar la presencia de ONI y el pronóstico del paciente.

DiseñoEstudio observacional retrospectivo.

ÁmbitoUCI polivalente.

PacientesFueron analizados todos los pacientes ingresados en UCI por IRA, de forma consecutiva, que requirieron VNI entre el 1 de enero de 1997 al 31 Diciembre de 2022.

Variables de interés principalesVariables clínicas iniciales, fracaso de la VNI, complicaciones, mortalidad hospitalaria y al año.

ResultadosFueron analizados 5972 pacientes, 1275 (21.3%) presentaban ONI. La edad media era de 68.2 ± 14.9 y el 60.2% eran hombres. La causa mas frecuente de ONI fue la enfermedad respiratoria crónica en 452 (35.5%) casos. Los pacientes con ONI eran de mayor edad, mayor índice de comorbilidad de Charlson y mayor fragilidad. El fracaso de la VNI ocurrió en 536 (42,0%) pacientes en el grupo ONI y en 1118 (23,8%) en el grupo sin ONI (p < 0,001). La mortalidad hospitalaria fue mayor en los pacientes con ONI (57,9% versus 16,4%; p < 0,001). La OR ajustada para mortalidad hospitalaria fue de 2,14 (IC 95% 1,98 a 2,31).

ConclusionesLa ONI es frecuente en los pacientes con VNI tratados con VNI y se relaciona con un peor pronóstico a corto y largo plazo.

Non-invasive respiratory devices, high-flow oxygen therapy by nasal cannula (HFNC) and non-invasive ventilation (NIV), have become useful tools for the management of acute respiratory failure (ARF), having demonstrated their usefulness in different entities.1,2 Although most of the evidence for the use of NIV is relegated to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with severe exacerbation, and acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema (ACPE), NIV can be proposed as a first-line treatment in almost any etiology of ARF, especially when endotracheal intubation is considered inadequate.3,4

Nowadays, a significant proportion of patients admitted to the ICU are elderly, with severe comorbidities and presenting frailty.5 These factors affect their physical, physiological and cognitive reserve, making them especially vulnerable to a stressful situation. When chronic pathology is advanced or the frailty situation is severe, the quality of life is so deteriorated that they are not candidates for receiving certain types of organ support.5 Among the measures adopted to adapt the therapeutic effort, do not intubate (DNI) order is the most frequent in patients with ARF.6 In these patients, the use of NIV as ceiling therapy is frequent.7

The use of NIV in patients with DNI order aims to reverse the acute illness and to promote patient comfort.7 The importance of DNI order is determined by its high prevalence and its impact on the prognosis of patients. DNI order is applied to nearly a quarter of patients with ARF and its incidence has increased in recent years.8 The relationship between DNI order and a worse prognosis has been established in different observational studies, which showed a high mortality rate, both in-hospital and in the long term.9–13 Recently, a systematic review showed an in-hospital survival rate of 56%, and 32% at one year in this population.14 Despite this, there is still significant controversy over the use of NIV, since it could lead to the prolongation of a chronic and irreversible process.15

The primary objective of this study was to describe the prevalence of DNI order in a large sample of patients with ARF. The secondary objective was to analyze the relationship between the presence of DNI order and the patients’ prognosis.

MethodsWe performed an observational and retrospective study of patients consecutively admitted for ARF to the ICU of an university hospital, in the period from January 1st, 1997, to December 31st, 2022. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution (Code EXT:10/23; approved on March 6, 2023).

PatientsWe included all consecutive patients with hypoxemic ARF or exacerbated hypercapnic chronic respiratory failure that met the selection criteria. Patients were included if they required non-invasive CPAP or bilevel positive pressure ventilation. The indication included all three criteria: a) moderate to severe dyspnea, defined as the presence of dyspnea at rest or on minimal exertion; b) respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute (bpm); and c) presence of hypoxemia (defined as a PaO2/FiO2 less than 200 mmHg) and/or PaCO2 greater 45 mmHg with arterial pH less than 7.35. The initial respiratory support strategy was chosen by the attending physician, although the use of CPAP was prioritized when the respiratory rate was between 20 and 30, while NIV on bilevel mode was preferred if the respiratory rate was greater than 30, there were signs of muscle fatigue, respiratory acidosis on arterial blood gases or history of chronic respiratory disease. The need for immediate intubation due to respiratory exhaustion or cardiorespiratory arrest were considered contraindications to the use of CPAP/NIV. Patients who were transferred to other health centers during the first 12 h of ICU stay and those who only presented a need for chronic NIV due to sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome were also excluded.

A summary of the NIV protocol used in these patients is shown in the Supplementary material.

Analyzed variablesOn NIV starting, sociodemographic, clinical and analytical variables were collected. To assess the severity and comorbidities of the patient’s condition we calculated the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA), and the Charlson index (CCI). From 2010 onwards, the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) was calculated for all patients. This scale was calculated retrospectively in previously admitted patients after reviewing the clinical history of the previous 6 mo. The definitions of DNI order, main comorbidities and complications developed in the ICU are shown in Table S1 of the Supplementary material.

Patients were followed one year after admission to the ICU.

The decision to institute a DNI order was the result of a decision-making process agreed upon with the patient, the closest family members, and the entire ICU medical staff.16 Whenever possible, this was confirmed by the physician who regularly cared for the patient. Patients were classified as having a DNI order when their physical disability and underlying debilitating conditions made them poor candidates for intubation. At all times the patient and family received clear and complete information on the subject.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies, and comparisons between them were made using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and the comparison between independent groups using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test if the quantitative variable did not follow normal distribution. The parametric or nonparametric distribution of a continuous quantitative variable was performed by applying the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. The measures of association analyzed were odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Independent risk factors for determining DNI order and in-hospital mortality were analyzed using logistic regression. Variables identified as predictors of DNI order in the univariate analysis (p < 0.20), together with those considered relevant, were included in a multivariate logistic regression model using the stepwise forward method (PIN0.10, POUT0.05) to correct collinearity. Adjustment of confounding variables for the calculation of the relationship between in-hospital mortality and one-year mortality with DNI order was performed by calculating the adjusted OR and its 95% CI, using Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW). The IPW calculation was performed by adjusting for the following variables: year to admission, age, gender, body mass index, basal PaO2/FiO2, basal PaCO2, basal respiratory rate, SAPS II, initial SOFA, CCI, CFS, etiology of ARF, shock at NIV starting and C-reactive protein. A sensitivity analysis was performed including only patients admitted between 2020 and 2022.

The analysis was performed using the SPSS 25.0® program (IBM™, Armonk, NY) and R version 3.4.0® (Copyright 2017 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform™.

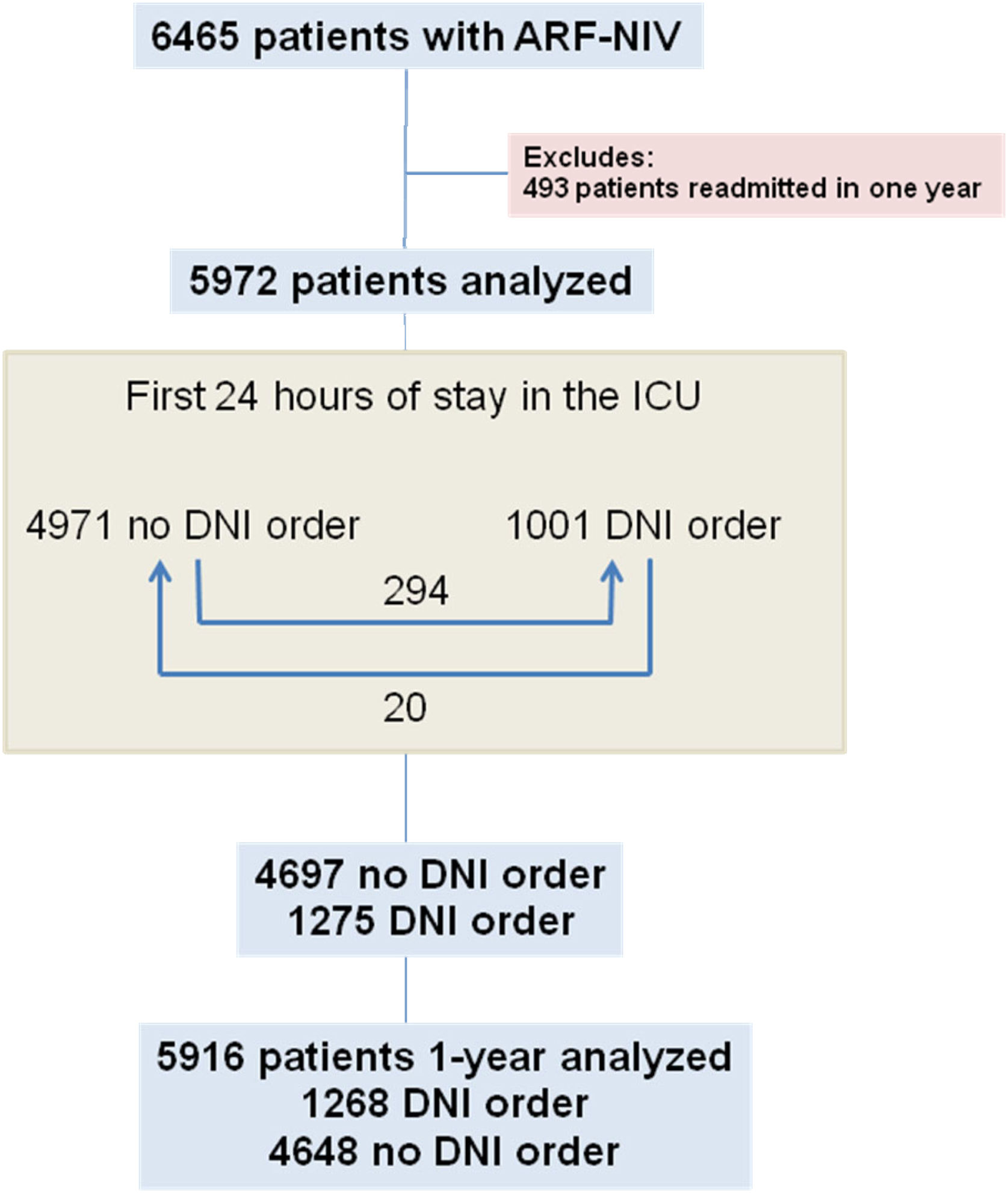

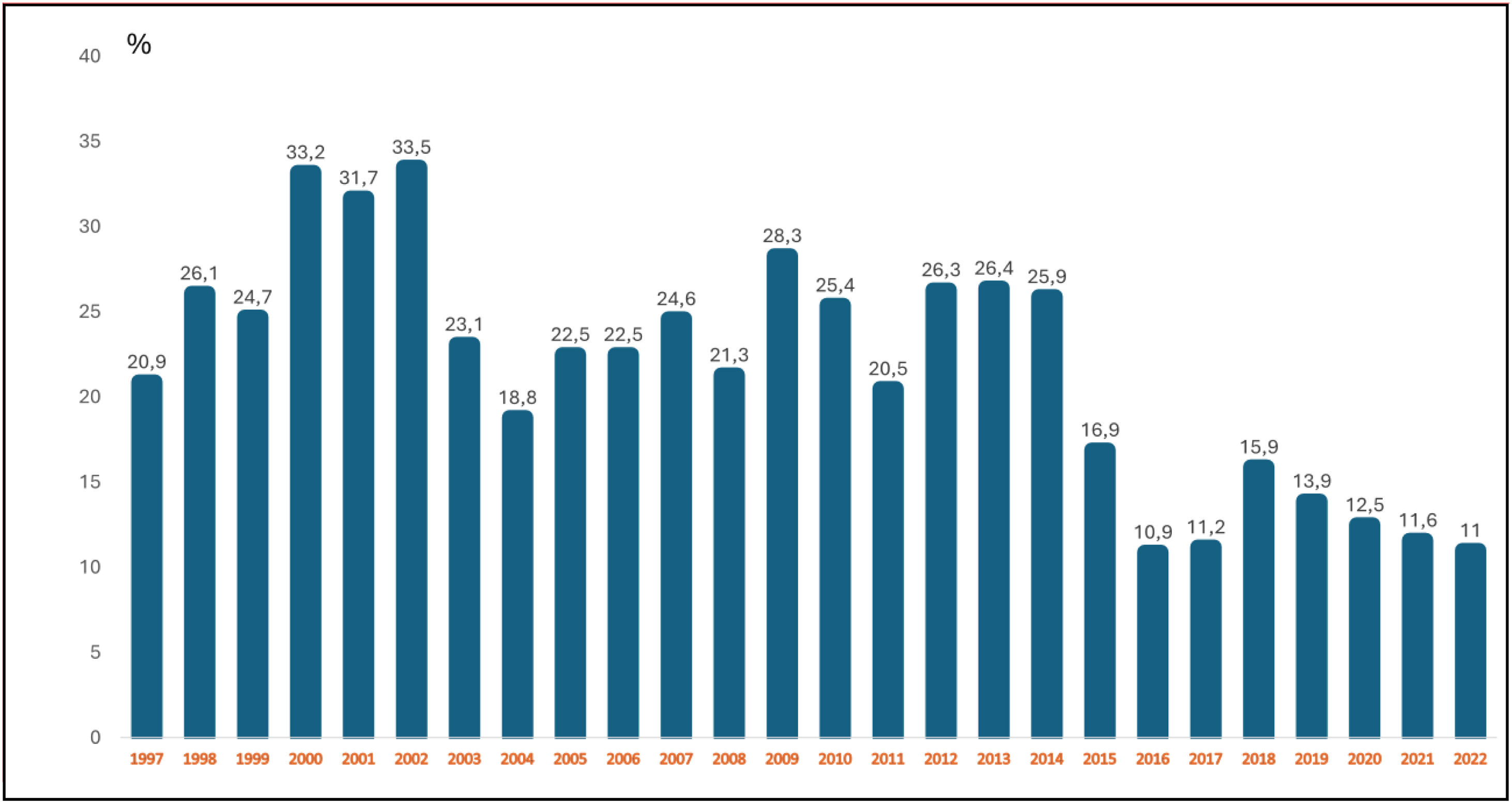

ResultsDuring the analyzed period, 6495 patients with ARF treated with NIV were admitted; 493 patients were excluded because they had been admitted previously. Finally, 5972 patients were analyzed. During the first 24 h of ICU stay, a DNI order was determined in 1001 patients. In the following days, 294 additional patients were determined to have a DNI order, while in 20 patients for whom a DNI order had initially been determined, it was decided to change it (Fig. 1). Finally, 1275 (21.3%) had a DNI order, with a decrease in the incidence over the years (Fig. 2). The reasons for the DNI order are shown in Fig. S1.

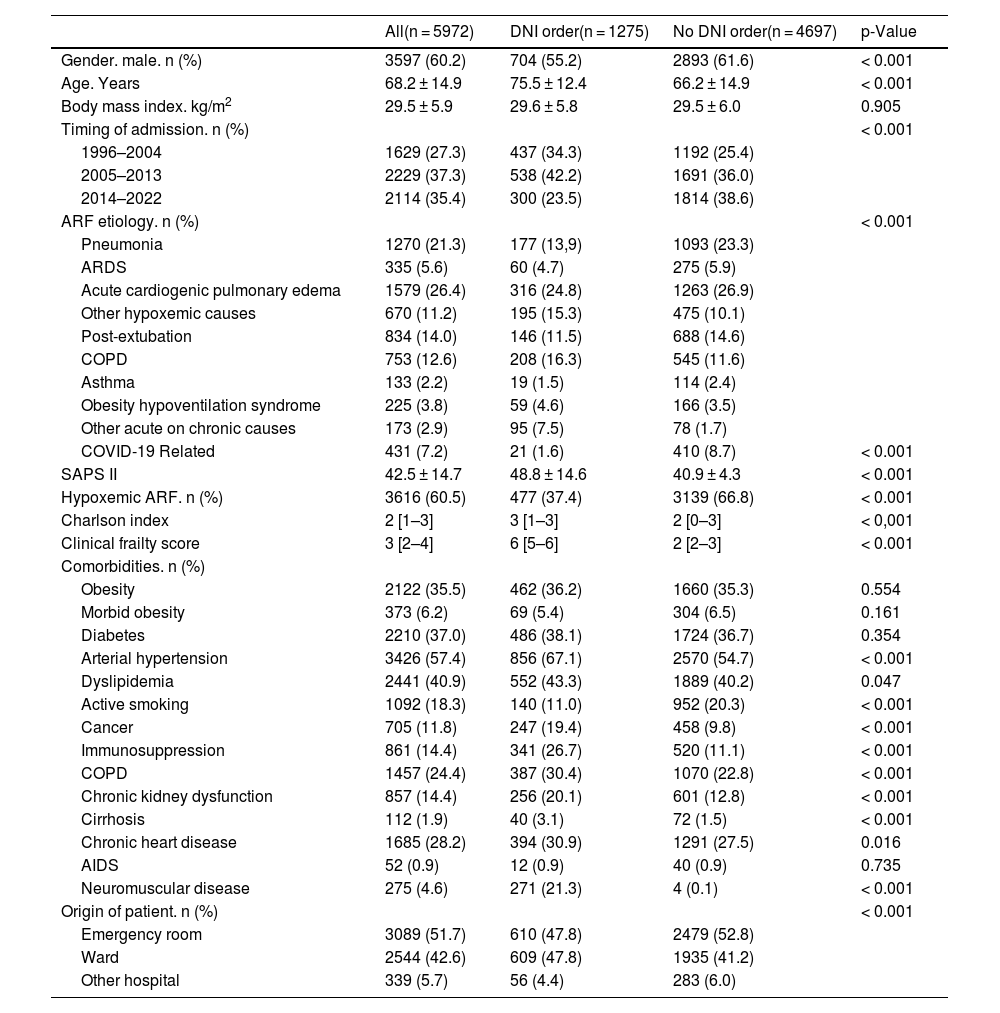

The main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 68.2 years, with a higher age in patients with DNI order, 75.5 versus 66.2 years (p < 0.001). Although the male gender was predominant in both groups, it was more frequent in patients without DNI order, 61.6% versus 55.2% (p < 0.001). The mean value of the SAPS II index, CCI and CFS were higher in patients with DNI order (p < 0.001). In the group with DNI order the most frequent etiologies were ACPE (24.8%), followed by COPD exacerbation (16.3%) and other hypoxemic etiologies (15.3%). In the group without DNI order ACPE was the most frequent etiology (26.9%), followed by pneumonia (23.3%) and post-extubation ARF (14.6%). Higher rates of history of cancer, immunosuppression and COPD were observed in patients with DNI order (p < 0.001). The independent predictor variables related to DNI order are shown in Fig. S2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| All(n = 5972) | DNI order(n = 1275) | No DNI order(n = 4697) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender. male. n (%) | 3597 (60.2) | 704 (55.2) | 2893 (61.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age. Years | 68.2 ± 14.9 | 75.5 ± 12.4 | 66.2 ± 14.9 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index. kg/m2 | 29.5 ± 5.9 | 29.6 ± 5.8 | 29.5 ± 6.0 | 0.905 |

| Timing of admission. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| 1996–2004 | 1629 (27.3) | 437 (34.3) | 1192 (25.4) | |

| 2005–2013 | 2229 (37.3) | 538 (42.2) | 1691 (36.0) | |

| 2014–2022 | 2114 (35.4) | 300 (23.5) | 1814 (38.6) | |

| ARF etiology. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Pneumonia | 1270 (21.3) | 177 (13,9) | 1093 (23.3) | |

| ARDS | 335 (5.6) | 60 (4.7) | 275 (5.9) | |

| Acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema | 1579 (26.4) | 316 (24.8) | 1263 (26.9) | |

| Other hypoxemic causes | 670 (11.2) | 195 (15.3) | 475 (10.1) | |

| Post-extubation | 834 (14.0) | 146 (11.5) | 688 (14.6) | |

| COPD | 753 (12.6) | 208 (16.3) | 545 (11.6) | |

| Asthma | 133 (2.2) | 19 (1.5) | 114 (2.4) | |

| Obesity hypoventilation syndrome | 225 (3.8) | 59 (4.6) | 166 (3.5) | |

| Other acute on chronic causes | 173 (2.9) | 95 (7.5) | 78 (1.7) | |

| COVID-19 Related | 431 (7.2) | 21 (1.6) | 410 (8.7) | < 0.001 |

| SAPS II | 42.5 ± 14.7 | 48.8 ± 14.6 | 40.9 ± 4.3 | < 0.001 |

| Hypoxemic ARF. n (%) | 3616 (60.5) | 477 (37.4) | 3139 (66.8) | < 0.001 |

| Charlson index | 2 [1–3] | 3 [1–3] | 2 [0–3] | < 0,001 |

| Clinical frailty score | 3 [2–4] | 6 [5–6] | 2 [2–3] | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities. n (%) | ||||

| Obesity | 2122 (35.5) | 462 (36.2) | 1660 (35.3) | 0.554 |

| Morbid obesity | 373 (6.2) | 69 (5.4) | 304 (6.5) | 0.161 |

| Diabetes | 2210 (37.0) | 486 (38.1) | 1724 (36.7) | 0.354 |

| Arterial hypertension | 3426 (57.4) | 856 (67.1) | 2570 (54.7) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2441 (40.9) | 552 (43.3) | 1889 (40.2) | 0.047 |

| Active smoking | 1092 (18.3) | 140 (11.0) | 952 (20.3) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 705 (11.8) | 247 (19.4) | 458 (9.8) | < 0.001 |

| Immunosuppression | 861 (14.4) | 341 (26.7) | 520 (11.1) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 1457 (24.4) | 387 (30.4) | 1070 (22.8) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney dysfunction | 857 (14.4) | 256 (20.1) | 601 (12.8) | < 0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 112 (1.9) | 40 (3.1) | 72 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic heart disease | 1685 (28.2) | 394 (30.9) | 1291 (27.5) | 0.016 |

| AIDS | 52 (0.9) | 12 (0.9) | 40 (0.9) | 0.735 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 275 (4.6) | 271 (21.3) | 4 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Origin of patient. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Emergency room | 3089 (51.7) | 610 (47.8) | 2479 (52.8) | |

| Ward | 2544 (42.6) | 609 (47.8) | 1935 (41.2) | |

| Other hospital | 339 (5.7) | 56 (4.4) | 283 (6.0) |

Quantitative variables are expressed as means ± deviation, or median (interquartile range).

AIDS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; ARF: acute respiratory failure; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DNI: do not intubate order; n: number; SAPS II: Simplified Acute Physiology Score.

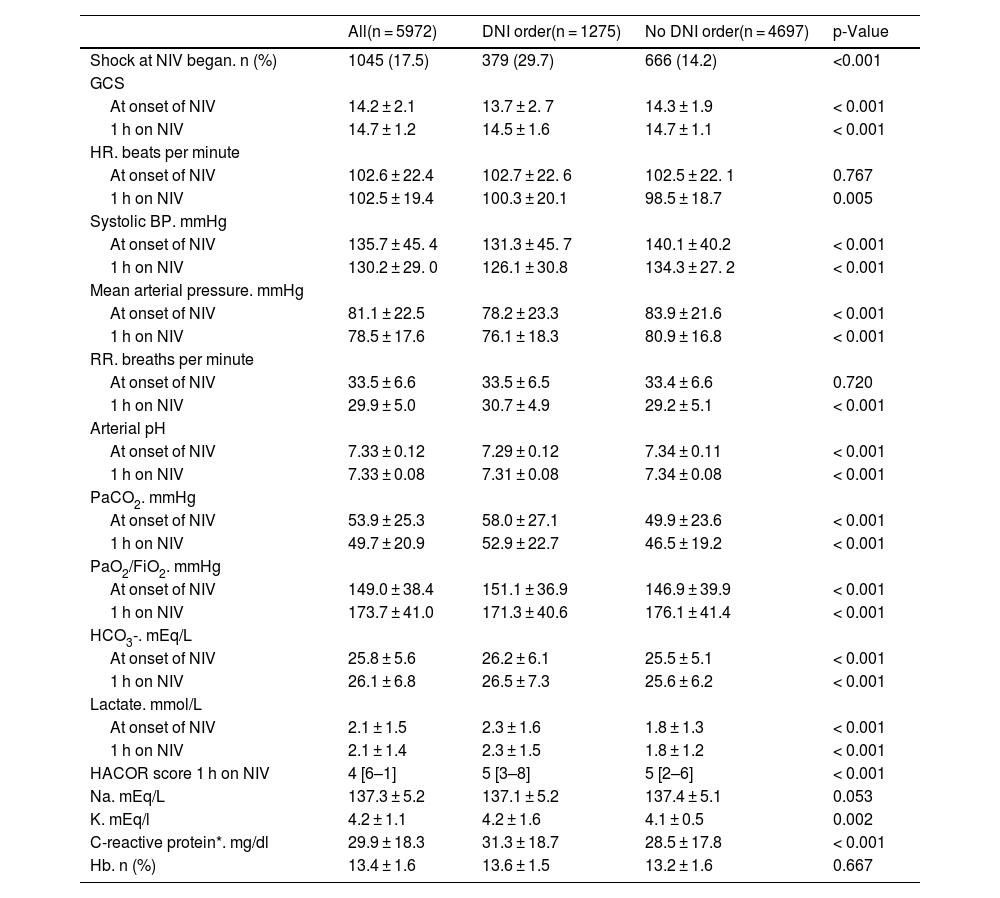

The hemodynamic, respiratory, neurological and analytical parameters of the patients in both groups are shown in Table 2. Most of the variables showed significant differences between the two groups. Both the oxygenation ratio and the initial pH were lower in the DNI order group (p < 0.001). The median HACOR score value at 1 h after starting NIV was 5 in both groups. Higher CRP values were found in the DNI order group, 23.4 ± 12.6 versus 20.2 ± 9.4 (p < 0.001).

Hemodynamic, neurological, respiratory and analytical parameters.

| All(n = 5972) | DNI order(n = 1275) | No DNI order(n = 4697) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shock at NIV began. n (%) | 1045 (17.5) | 379 (29.7) | 666 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| GCS | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 13.7 ± 2. 7 | 14.3 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 14.7 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 1.6 | 14.7 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| HR. beats per minute | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 102.6 ± 22.4 | 102.7 ± 22. 6 | 102.5 ± 22. 1 | 0.767 |

| 1 h on NIV | 102.5 ± 19.4 | 100.3 ± 20.1 | 98.5 ± 18.7 | 0.005 |

| Systolic BP. mmHg | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 135.7 ± 45. 4 | 131.3 ± 45. 7 | 140.1 ± 40.2 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 130.2 ± 29. 0 | 126.1 ± 30.8 | 134.3 ± 27. 2 | < 0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure. mmHg | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 81.1 ± 22.5 | 78.2 ± 23.3 | 83.9 ± 21.6 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 78.5 ± 17.6 | 76.1 ± 18.3 | 80.9 ± 16.8 | < 0.001 |

| RR. breaths per minute | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 33.5 ± 6.6 | 33.5 ± 6.5 | 33.4 ± 6.6 | 0.720 |

| 1 h on NIV | 29.9 ± 5.0 | 30.7 ± 4.9 | 29.2 ± 5.1 | < 0.001 |

| Arterial pH | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 7.33 ± 0.12 | 7.29 ± 0.12 | 7.34 ± 0.11 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 7.33 ± 0.08 | 7.31 ± 0.08 | 7.34 ± 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2. mmHg | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 53.9 ± 25.3 | 58.0 ± 27.1 | 49.9 ± 23.6 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 49.7 ± 20.9 | 52.9 ± 22.7 | 46.5 ± 19.2 | < 0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2. mmHg | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 149.0 ± 38.4 | 151.1 ± 36.9 | 146.9 ± 39.9 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 173.7 ± 41.0 | 171.3 ± 40.6 | 176.1 ± 41.4 | < 0.001 |

| HCO3-. mEq/L | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 25.8 ± 5.6 | 26.2 ± 6.1 | 25.5 ± 5.1 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 26.1 ± 6.8 | 26.5 ± 7.3 | 25.6 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 |

| Lactate. mmol/L | ||||

| At onset of NIV | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| 1 h on NIV | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| HACOR score 1 h on NIV | 4 [6–1] | 5 [3–8] | 5 [2–6] | < 0.001 |

| Na. mEq/L | 137.3 ± 5.2 | 137.1 ± 5.2 | 137.4 ± 5.1 | 0.053 |

| K. mEq/l | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 0.002 |

| C-reactive protein*. mg/dl | 29.9 ± 18.3 | 31.3 ± 18.7 | 28.5 ± 17.8 | < 0.001 |

| Hb. n (%) | 13.4 ± 1.6 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 0.667 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation, or median [Interquartile range].

BP: Blood pressure; DNI: do not intubate; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; HACOR: heart, acidosis, consciousness, oxygenation, respiratory; Hb: hemoglobin; HCO3-: bicarbonate; HR: heart rate; mEq/L: milliequivalent per liter; mg/dl: milligrams per deciliter; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; mmol/L: millimoles per liter; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; n: number; PaCO2: partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide; PaO2: partial pressure of arterial oxygen, RR: respiration rate.

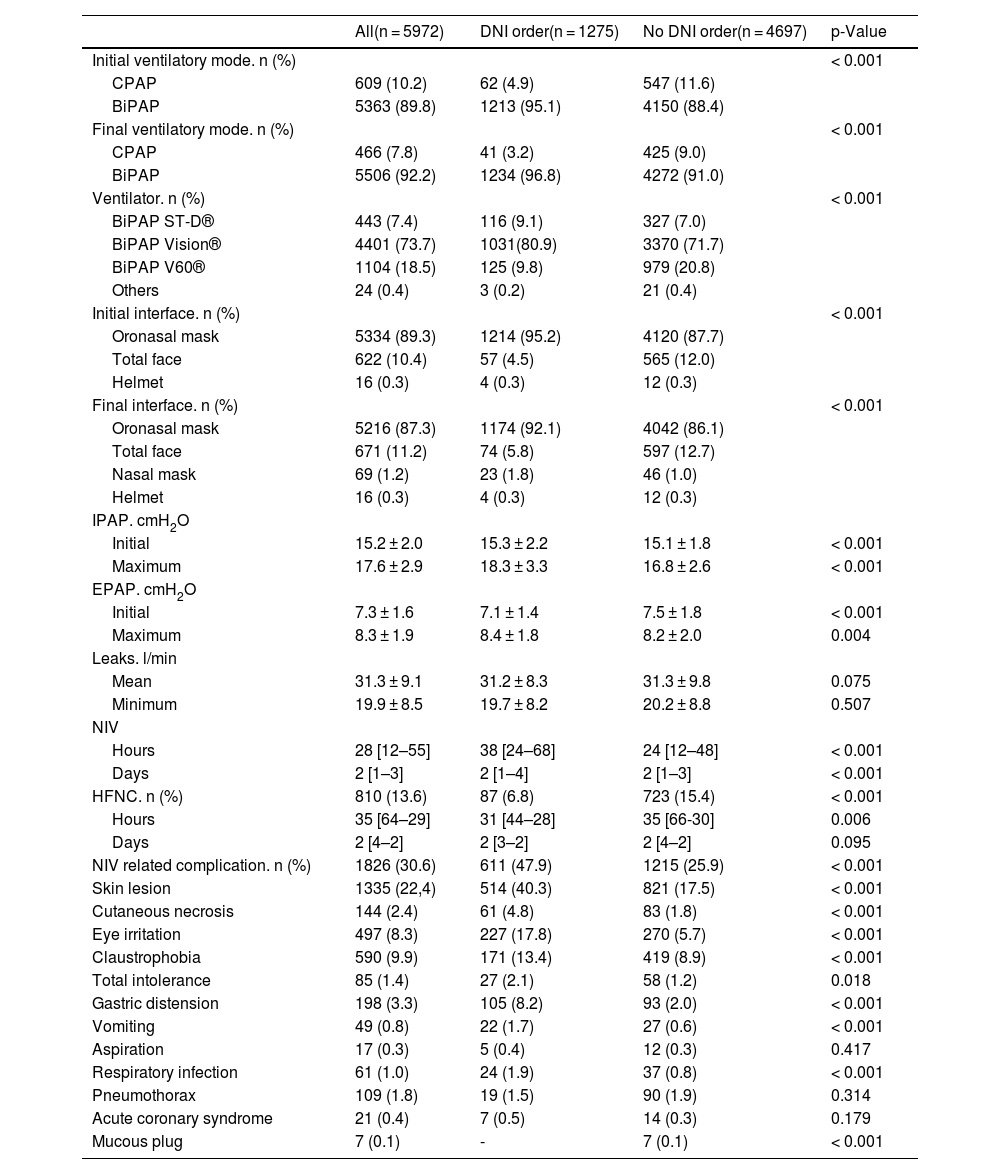

Table 3 shows the main ventilatory parameters in the two groups. NIV in bilevel mode was used more frequently in patients with DNI order (p < 0.001). Although the most used interface in both groups was the oronasal, it was more frequently used in the DNI order group (92.1% versus 86.1%; p < 0.001). The duration of NIV was longer in the DNI order group: median of 38 h versus 24 h (p < 0.001). NIV-related complications were more frequent in the DNI order group (40.3% versus 17.5%, p < 0.001).

Ventilatory parameters.

| All(n = 5972) | DNI order(n = 1275) | No DNI order(n = 4697) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial ventilatory mode. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| CPAP | 609 (10.2) | 62 (4.9) | 547 (11.6) | |

| BiPAP | 5363 (89.8) | 1213 (95.1) | 4150 (88.4) | |

| Final ventilatory mode. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| CPAP | 466 (7.8) | 41 (3.2) | 425 (9.0) | |

| BiPAP | 5506 (92.2) | 1234 (96.8) | 4272 (91.0) | |

| Ventilator. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| BiPAP ST-D® | 443 (7.4) | 116 (9.1) | 327 (7.0) | |

| BiPAP Vision® | 4401 (73.7) | 1031(80.9) | 3370 (71.7) | |

| BiPAP V60® | 1104 (18.5) | 125 (9.8) | 979 (20.8) | |

| Others | 24 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 21 (0.4) | |

| Initial interface. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Oronasal mask | 5334 (89.3) | 1214 (95.2) | 4120 (87.7) | |

| Total face | 622 (10.4) | 57 (4.5) | 565 (12.0) | |

| Helmet | 16 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | |

| Final interface. n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Oronasal mask | 5216 (87.3) | 1174 (92.1) | 4042 (86.1) | |

| Total face | 671 (11.2) | 74 (5.8) | 597 (12.7) | |

| Nasal mask | 69 (1.2) | 23 (1.8) | 46 (1.0) | |

| Helmet | 16 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | |

| IPAP. cmH2O | ||||

| Initial | 15.2 ± 2.0 | 15.3 ± 2.2 | 15.1 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Maximum | 17.6 ± 2.9 | 18.3 ± 3.3 | 16.8 ± 2.6 | < 0.001 |

| EPAP. cmH2O | ||||

| Initial | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Maximum | 8.3 ± 1.9 | 8.4 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 2.0 | 0.004 |

| Leaks. l/min | ||||

| Mean | 31.3 ± 9.1 | 31.2 ± 8.3 | 31.3 ± 9.8 | 0.075 |

| Minimum | 19.9 ± 8.5 | 19.7 ± 8.2 | 20.2 ± 8.8 | 0.507 |

| NIV | ||||

| Hours | 28 [12–55] | 38 [24–68] | 24 [12–48] | < 0.001 |

| Days | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–3] | < 0.001 |

| HFNC. n (%) | 810 (13.6) | 87 (6.8) | 723 (15.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hours | 35 [64–29] | 31 [44–28] | 35 [66-30] | 0.006 |

| Days | 2 [4–2] | 2 [3–2] | 2 [4–2] | 0.095 |

| NIV related complication. n (%) | 1826 (30.6) | 611 (47.9) | 1215 (25.9) | < 0.001 |

| Skin lesion | 1335 (22,4) | 514 (40.3) | 821 (17.5) | < 0.001 |

| Cutaneous necrosis | 144 (2.4) | 61 (4.8) | 83 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Eye irritation | 497 (8.3) | 227 (17.8) | 270 (5.7) | < 0.001 |

| Claustrophobia | 590 (9.9) | 171 (13.4) | 419 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| Total intolerance | 85 (1.4) | 27 (2.1) | 58 (1.2) | 0.018 |

| Gastric distension | 198 (3.3) | 105 (8.2) | 93 (2.0) | < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 49 (0.8) | 22 (1.7) | 27 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Aspiration | 17 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 12 (0.3) | 0.417 |

| Respiratory infection | 61 (1.0) | 24 (1.9) | 37 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumothorax | 109 (1.8) | 19 (1.5) | 90 (1.9) | 0.314 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 21 (0.4) | 7 (0.5) | 14 (0.3) | 0.179 |

| Mucous plug | 7 (0.1) | - | 7 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

BiPAP: bilevel positive airway pressure; cmH2O: centimeters of water; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; EPAP: expiratory positive airway pressure; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; HFNC: High flow nasal cannula; IPAP: inspiratory positive airway pressure; l/min: liters per minute; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; n: number.

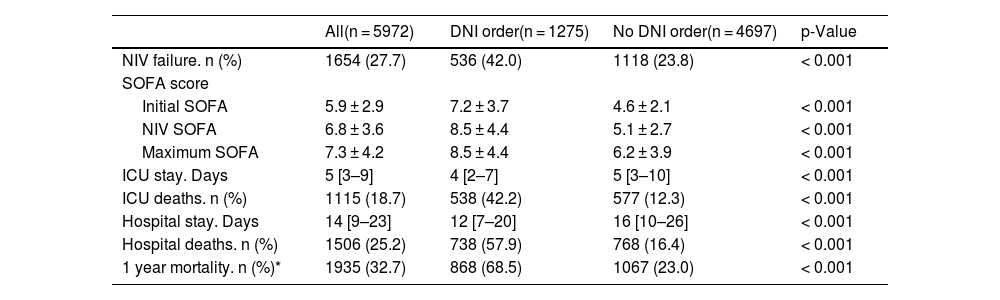

Patient outcomes are shown in Table 4. The NIV failure rate in patients with DNI order was 42% versus 23.8% in the group without DNI order (p < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was higher in patients with DNI order (crude OR: 7.03, 95% CI 6.14 to 8.05). When adjusted for IPW, the adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality was 2.14 (95% CI 1.98 to 2.31). Sensitivity analysis, including only patients admitted between 2020 to 2022, also showed differences between the two groups for NIV failure (OR: 9.64, 95% CI 6.11 to 15.21) and in-hospital mortality (OR 16.45, 95% CI 9.26 to 29.22) [Table S2]. When adjusted for IPW, the adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality in the subgroup of patients admitted between 2020 to 2022 was 3.49 (95% CI 2.84 to 4.31). Among patients with DNI order, the lowest in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates were in patients with COPD, acute asthma, and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome (Table S3).

Patients’ Evolution and Outcome.

| All(n = 5972) | DNI order(n = 1275) | No DNI order(n = 4697) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIV failure. n (%) | 1654 (27.7) | 536 (42.0) | 1118 (23.8) | < 0.001 |

| SOFA score | ||||

| Initial SOFA | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 7.2 ± 3.7 | 4.6 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| NIV SOFA | 6.8 ± 3.6 | 8.5 ± 4.4 | 5.1 ± 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| Maximum SOFA | 7.3 ± 4.2 | 8.5 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| ICU stay. Days | 5 [3–9] | 4 [2–7] | 5 [3–10] | < 0.001 |

| ICU deaths. n (%) | 1115 (18.7) | 538 (42.2) | 577 (12.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay. Days | 14 [9–23] | 12 [7–20] | 16 [10–26] | < 0.001 |

| Hospital deaths. n (%) | 1506 (25.2) | 738 (57.9) | 768 (16.4) | < 0.001 |

| 1 year mortality. n (%)* | 1935 (32.7) | 868 (68.5) | 1067 (23.0) | < 0.001 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

DNI: do not intubate; ICU: intensive care unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; n: number; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Fig. S3 shows the decrease in the rate of DNI order produced over the years of the study, divided into three periods (years 1997–2004, 2005–2013 and 2014–2022), in relation to the type of ARF. Through the periods analyzed, a lower number of patients admitted with exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure, and an increase in hypoxemic ARF were observed. Although in both types of ARF the rates of DNI order decreased along the three periods analyzed, 37.9%, 35.4% and 24.9%, respectively, in exacerbation of hypercapnic chronic respiratory failure (p < 0.001), and 12.8%, 16.7% and 10.4%, respectively, in hypoxemic ARF (p = 0.007), the rate of DNI order remained twice as high in patients with exacerbation of hypercapnic chronic respiratory failure than in hypoxemic ARF patients. Patients with active cancer also showed a decrease in the presence of DNI order over time. During the first period, 48.2% of the patients with active cancer had DNI order, while in the second period that value decreased to 39.4%, and in the last period to 33.1% (p = 0.006).

DiscussionIn our study, where we used NIV as respiratory support to prevent a fatal outcome and not as a palliative measure to minimize symptoms, the prevalence of DNI order in patients with ARF treated with NIV was high (21.3%). However, a progressive decrease was observed in the last decade, being 11.9% in recent years. The prevalence of DNI order in different studies is very variable, depending on the type of patients, the geographic area8 and the allocation of the patient in the hospital, with a lower rate in those admitted to the ICU compared to those admitted to intermediate care units or conventional wards.9–13 In a recent systematic review, 27% of patients with ARF had a DNI order, with a wide variability between studies (9–58%).14 The decrease observed in our series could be related to the characteristics of patients admitted to the ICU, especially the decrease in patients with exacerbation of hypercapnic chronic respiratory failure and the increase in hypoxemic ARF. This fact may be related to the greater current availability of NIV in conventional hospitalization wards, where mainly patients with chronic or less severe hypoxemic pathologies are admitted.4 On the other hand, the decrease in DNI order in patients with active cancer is evident in view of the availability of new medications that increase the survival and quality of life of these patients, including intubated patients.16 It remains to be clarified whether, over the years, new generations of intensive care physicians have changed their perspective on the management of patients with chronic diseases, or whether the worse prognosis of these patients (even those treated with NIV in the ICU) represents an impediment to the time to consult them and admit them to the ICU.

Defining an adequate therapeutic effort is a common practice in critical care areas. Of these, DNI order is one of the most frequent. Although the use of NIV in the treatment of advanced disease, both as support or to improve comfort, has been widely debated15,17 due to the possibility of increasing the agony of both the patient and the family, it has become a common practice in DNI order patients. In fact, in the systematic review carried out by Wilson et al., the establishment of DNI order has increased in recent years,8 unlike what occurred in our study.

The factors influencing the decision on a DNI order are multiple, and are mainly related to age, associated comorbidities, the patient’s baseline and frailty status, the prognosis of the underlying disease, and the expectations and wishes of the patient and family.8 Among the factors related to the patient, older age,9,12,18–20 higher comorbidity21,22 and lower baseline status,12 are more frequent in patients with DNI order. In our study, patients with DNI order were older, had a greater number of comorbidities and were frailer than patients eligible for “full” treatment. As in other studies, the pathologies most frequently associated with DNI order in our patients were chronic cardiorespiratory and neurological diseases.11,22 However, in recent years, advanced oncological pathology has become one of the fundamental causes for establishing DNI order. The use of NIV as ceiling therapy in haemato-oncological patients with ARF, despite the controversy over its use, is an effective tool that in many cases can solve the clinical problem that motivated hospital admission, without worsening the quality of life previously shown by the patient.12,16

In our study, neurological, hemodynamic and respiratory parameters did not show relevant differences between patients with and without DNI order. For this reason, the ventilatory parameters used during NIV were very similar. As a single exception, we had the highest level of maximum IPAP in patients with DNI order, which was related to a higher level of PaCO2 and lower pH. The duration of NIV was longer in patients with DNI order, since patients with this limitation of therapeutic effort were usually maintained on non-invasive support until clinical improvement or death. Duan et al., in a study that analyzed the duration of NIV, found that DNI order was an independent predictive factor for prolonged NIV.23 Complications related to NIV are frequent but generally not serious.24 In our series, patients with DNI order presented more frequent complications of NIV, which were related to the longer duration of this kind of respiratory support.

The prognosis of patients with ARF and DNI order is poor. In our study, in-hospital mortality rate was 57.9%. The different series that have addressed the use of NIV in this type of patients show very variable hospital mortality rates. Scarpazza et al. in a series of 62 patients with acute on chronic respiratory failure, showed a mortality of 11.3%.25 Lemyze et al., in a series of patients with acute on chronic respiratory failure and impaired consciousness, had an in-hospital mortality rate of 28%.26 However, most series show higher mortality. It was 44% in the series by Azoulay et al.,12 48.5% in the pneumonia series by Brambilla et al.,27 71.1% in the series by Bulow et al.,28 56.1% in Schetino et al.,11 74% in Fernandez et al.13 and 55% in Meduri et al.29

Long-term survival is very short. In the study by Bullow et al.28 with a 5-year follow-up, survival rate was 11%. Chu et al. showed a one-year survival rate of 29.7% in COPD patients.9

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has led to the need for in-patient and intermediate care unit treatment for many patients with ARF. DNI order and mortality rates have been highly variable. Aliberti et al.,30 in a multicenter study, showed a DNI order rate of 41.4%, while it was up to 50% in the case of Faraone et al.31 or Kofod et al.32 Van der Veer et al. published a series of 39 patients with DNI order, out of a total of 100, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 48.7%.19 However, other authors showed higher mortality rates. Bradley et al. reported a mortality rate of 70% at 30 days,33 while Holm et al.34 observed mortality rates of 81% in those with DNI order. These results are similar to those observed in Italy with mortality rates close to 90%.31,35 In a recent systematic review by Cammarota et al.36 evaluating the use of non-invasive respiratory devices in 31 observational studies with 6645 patients, the DNI order rate was 25.4% and in-hospital mortality was 83.6%.

The presence of DNI order has been identified as an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality in both patients with COVID-19 pneumonia37 and non-COVID patients.27 In our study, tanto univariate analysis as adjusted analysis of multiple confounding variables showed that the presence of DNI order as an independent predictive factor for increased in-hospital mortality.

The relationship between the cause of ARF and the prognosis of patients with DNI order is not the same in all pathologies. In our study, the survival of patients with COPD, asthma and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome was higher than in other etiologies. This finding has also been described by other authors, with better survival rates in COPD and acute heart failure,10,11 than in patients with hypoxemic ARF11 secondary to cancer38 or interstitial lung disease.39

This study has important strengths. First, this is a study with a large sample size, with a wide variety of clinical diagnoses, encompassing patients with hypoxemic ARF and exacerbation of hypercapnic chronic respiratory failure, which presents a broad spectrum of diseases that condition the presence of respiratory failure. Second, multiple variables were evaluated and systematically collected. The limitations of the study are related to the observational and retrospective nature of its design. On the other hand, it is a single-center study, in an ICU with extensive experience in the management of patients with NIV, highly qualified personnel and multiple devices for the treatment of these patients, which can affect the generalization of the results. Therefore, the external validity of the study may be compromised, and the results obtained may not be extrapolated to other units with less means or experience. Third, while the determination of the DNI usually requires a unanimous criterion not only with the patient or the family, but with all the medical doctors in the ICU, in our study this decision was sometimes taken by the doctors on duty without being able to be endorsed by the rest of the medical staff. Despite the presence of these limitations, we believe that they do not invalidate the results.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of DNI order was frequent in patients with ARF admitted to the ICU, being related to age, comorbidity, frailty and the underlying disease. NIV as a respiratory support measure to restore the previous state of health was an effective tool in these patients. The mortality of patients with DNI order was high, both in-hospital and in the long term, with patients with chronic respiratory disease being those who can benefit the most from NIV.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAndres Carrillo-Alcaraz: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Miguel Guia: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Pilar Tornero-Yepez: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Laura López-Gómez: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Nuria Alonso-Fernandez: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Juan Gervasio Martin-Lorenzo: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Juan Miguel Sanchez-Nieto: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo form of artificial intelligence was used.

FundingNone. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

None.