The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the interest in studying post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), with a significant increase in the number of research groups and publications related to this field in recent years1–4.

Traditionally, the activity of specialists in critical care has been confined to what happens “within the walls” of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The evidence that the outcomes are largely dependent upon what happens prior to patient admission caused members of our scientific societies to become involved in the organization of out-hospital care and the hospital emergency services5. Subsequently, attention focused on early detection and intervention in the case of patient worsening in the hospital wards6,7, and finally on the follow-up of patients after ICU discharge to both the ward and from the hospital.

Participation in post-intensive care follow-up programs usually involves medical and nursing staff2,8, but no data are available on the implication in such programs of trainees in Intensive Care Medicine.

To establish the possible impact of knowing the consequences of prolonged ICU stay upon the routine clinical practice of intensivists, we decided to explore the degree of interest and involvement of residents in training in this field.

With this aim, we developed an online questionnaire that was distributed through the SEMICYUC Joven Group during the months of September and October 2022. Participation in the study was voluntary, and completion of the questionnaire following the information given to the participants was taken to constitute consent to the analysis of the data.

The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions (6 demographic questions, 3 questions on knowledge of PICS, 4 questions on the post-intensive care follow-up program, and 2 questions on resident training in follow-up). The questionnaire is available as supplementary material. A descriptive statistical analysis was made of the data obtained, together with a bivariate analysis with contingency tables and the application of the chi-square test.

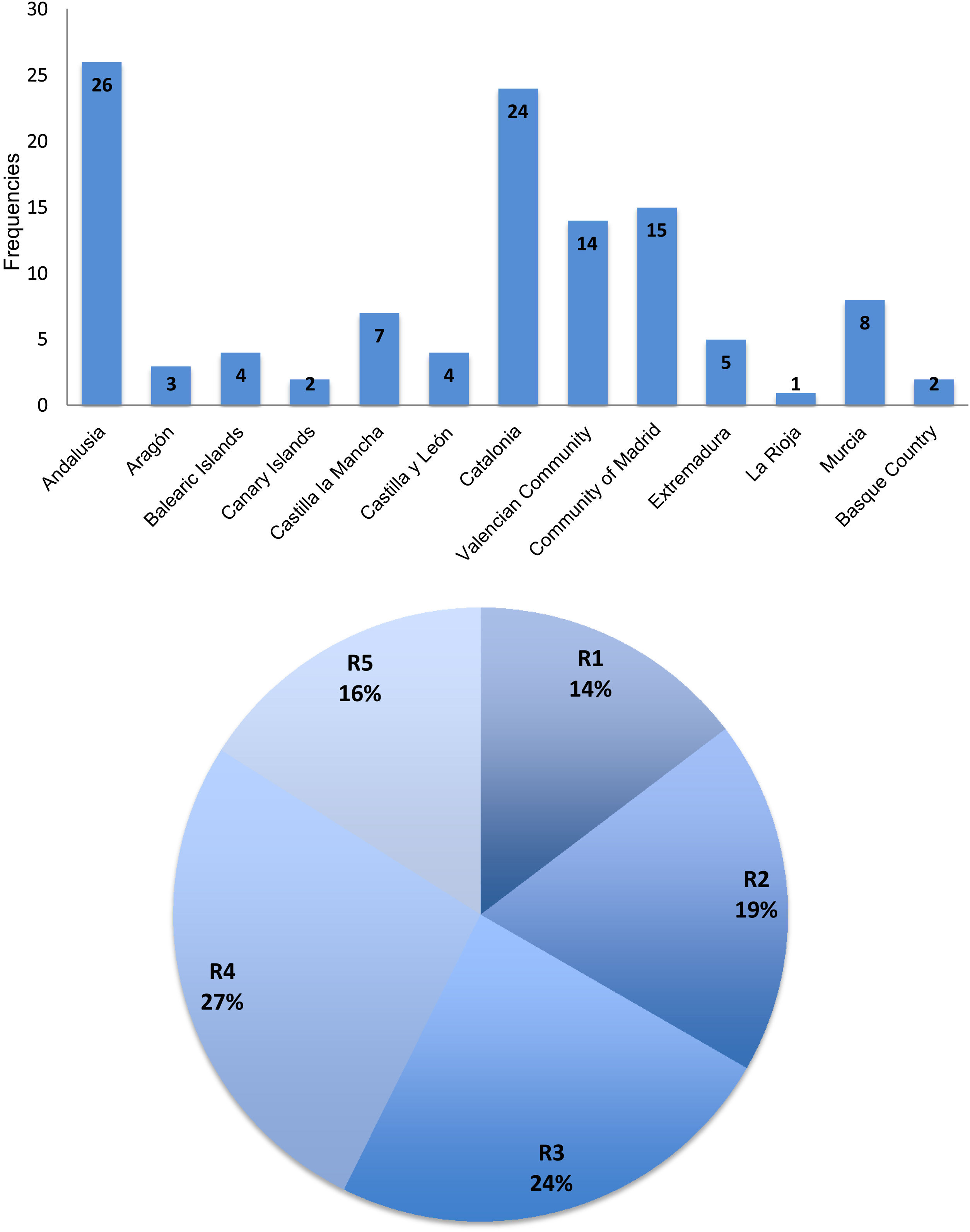

The questionnaire was sent to 140 members, of which 115 responded: 75 residents (65.2%) and 40 staff physicians under 35 years of age. The mean age of the participants was 34.9 years (range 28–40), and 67% were women. Only 7% of the participants had undergone some other residency before starting Intensive Care Medicine. The distribution by Spanish regions (Autonomous Communities) and year of residency is shown in Fig. 1.

Of the 115 participants in the study, 114 had knowledge of PICS, and 53% already had such knowledge before the COVID-19 pandemic. Forty-seven percent of the participants claimed to have a strong interest in PICS.

Forty percent of the participants had a post-intensive care follow-up program in the ICU where their training took place. The activities mainly involved the evaluation of the patients, and also of the relatives in 28% of the cases. Of the participants working in Units with post-intensive care follow-up programs, 20% claimed to participate actively in them. In this subgroup, 48% believed that participation in patient follow-up had modified their routine clinical practice.

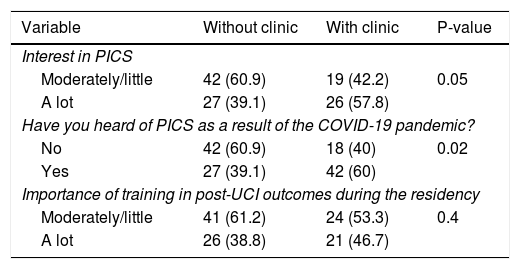

Training in post-intensive care follow-up during the residency period was considered to be relevant by 47% of the participants, and 95.6% were in favor of participating in training programs. Table 1 shows the differential features regarding the existence or absence of a post-intensive care follow-up clinic.

Differential features regarding the existence or absence of a post-intensive care follow-up clinic.

| Variable | Without clinic | With clinic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest in PICS | |||

| Moderately/little | 42 (60.9) | 19 (42.2) | 0.05 |

| A lot | 27 (39.1) | 26 (57.8) | |

| Have you heard of PICS as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic? | |||

| No | 42 (60.9) | 18 (40) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 27 (39.1) | 42 (60) | |

| Importance of training in post-UCI outcomes during the residency | |||

| Moderately/little | 41 (61.2) | 24 (53.3) | 0.4 |

| A lot | 26 (38.8) | 21 (46.7) | |

The results of the questionnaire among the residents in Intensive Care Medicine shows an increasing interest in PICS as an important clinical aspect of our care activities. This interest and the degree of knowledge of post-intensive care follow-up appear to be influenced by the Unit in which training takes place, with a clear association with the existence or absence of a specific consulting room or clinic. In either case, however, the residents attribute importance to and are in favor of receiving training in post-intensive care follow-up. Of note is the fact that approximately half of the residents participating in the care of such patients acknowledged that participation had modified their practice as intensivists. A review of the literature revealed no other studies on these aspects of post-intensive care follow-up training; no comparative analysis can therefore be made.

Measures have begun to be introduced in Spain for the prevention, identification and management of PICS. In 2017, as a pioneering initiative, the ICU of Hospital Universitario La Paz8 shared its program for the identification and follow-up of patients with PICS. Through a multidisciplinary team coordinated by an intensivist, a structured protocol is applied for the monitoring of patients at risk in the hospital ward 5-7 days after ICU discharge, three months after, and – if necessary – 6, 9 and 12 months after ICU discharge. The activities in the follow-up clinic comprise an evaluation of the three dimensions of PICS: physical, cognitive and psychological. Initiatives such as these have contributed to the creation of an increasing number of post-intensive care follow-up programs in Spain1–3. A national task force known as ITACA9 has been established with the aim of offering the best quality of care for patients also “after” they have survived the critical illness.

Although many studies support the need to minimize the risk factors associated with PICS during admission to the ICU4,10, no data are available on the importance for intensivists to work in post-intensive care follow-up programs. This brief questionnaire evidences the interest of residents training in Intensive Care Medicine in Spain, and emphasizes the importance of developing training programs in this field during the residency period. Further studies are needed to quantify the impact of these programs upon the patients and on the way in which intensivists focus their daily practice.

The authors thank the SEMICYUC Joven Group for its contribution to the diffusion of the questionnaire used in this study.