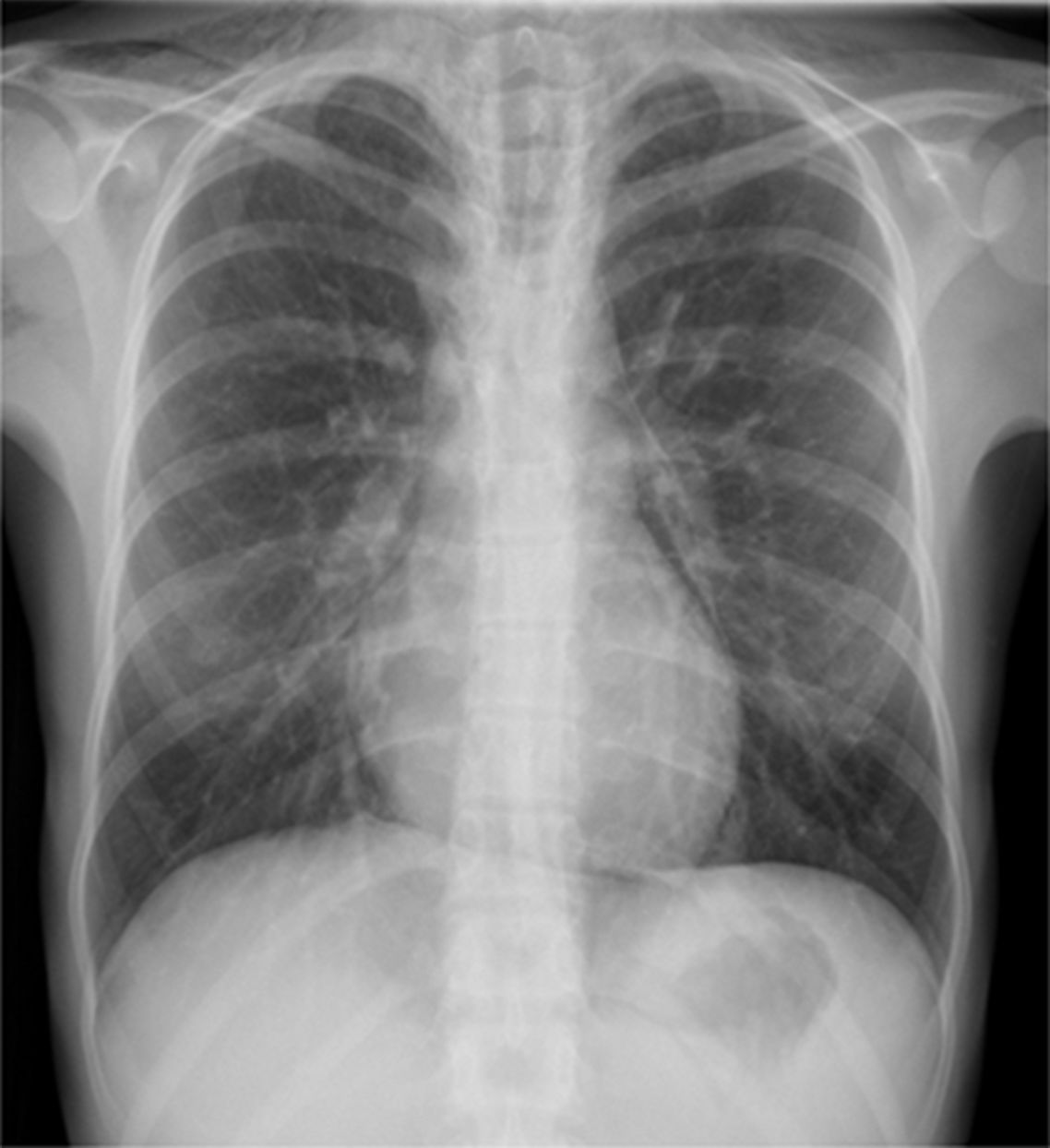

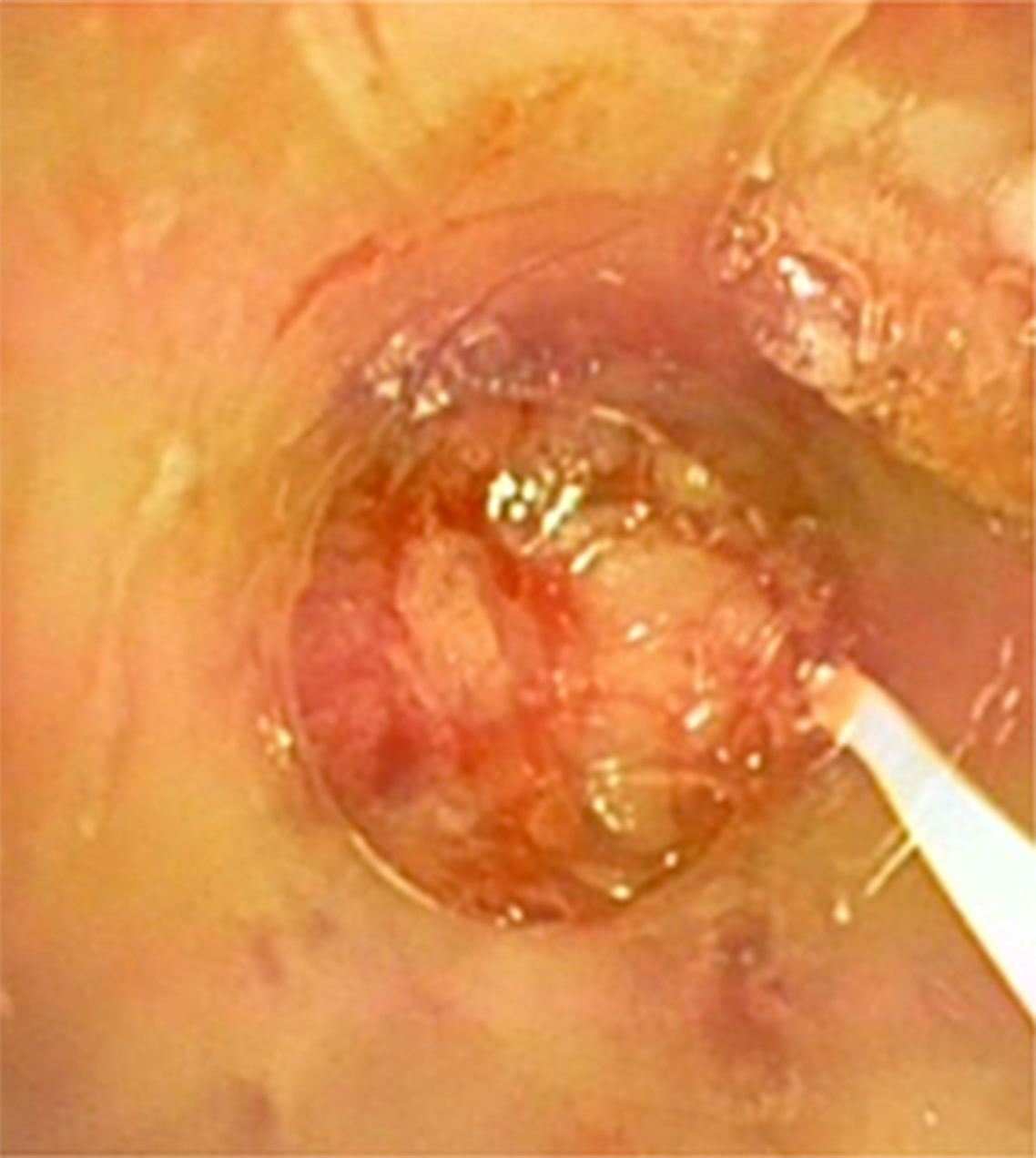

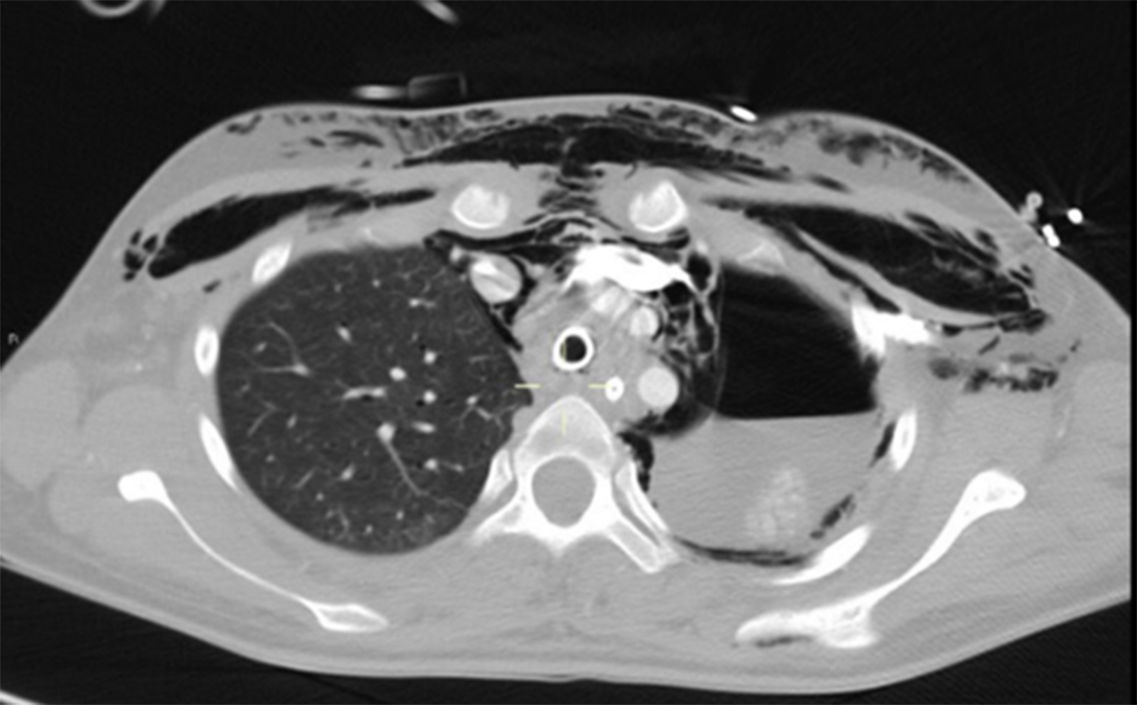

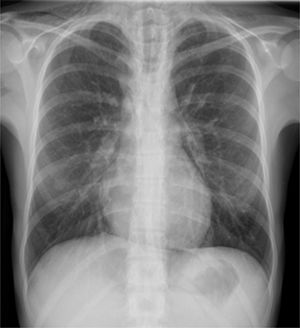

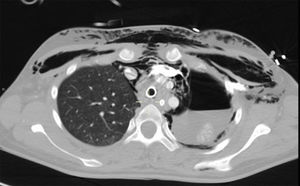

We hereby present here the case of a previously healthy 15-year-old female hospitalized with fever, nonproductive cough, and respiratory failure. Six weeks prior to being hospitalized she had started with mild and intermittent clinical manifestations of watery diarrhea, with fever and dry cough over a two-week period. In an outpatient consultation conducted ten days prior to being hospitalized, the blood test results were confirmed leukocytosis (15,660/mm3), anemia (Hb 11g/dL), mild elevation of transaminase levels (AST/ALT 62/75IU/L), and significant elevation of CRP levels (243mg/dL). Treatment with azithromycin and ambroxol was administered with no improvement whatsoever. She was admitted to the ER on several occasions due to clinical manifestations of persistent fever, cough, and mild dyspnea. The medical examination confirmed the presence of sinus tachycardia, wheezing, and relative hypoxemia, and the chest X-ray conducted confirmed signs of hyperinflation too. In her last visit to the ER, the patient had more severe hypoxemia (SaO2 87%), the chest X-ray showed pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema (Fig. 1), and the blood test results confirmed leukocytosis (23.590/mm3) with neutrophilia (78%), anemia (Hb 10g/dL), thrombocytosis (643,000/mm3), elevation of the CRP levels (180mg/dL, and procalcitonin (21ng/mL). She was hospitalized with oxygen therapy, inhaled ipratropium bromide and budesonide, methylprednisolone (20mg/12h) and levofloxacin. Within a few hours she suffered from severe respiratory failure that became agonic, with severe jugular ingurgitation, hypoxemia, and extreme respiratory acidosis (SaO2 37% via a face mask of high FiO2 and PaCO2 144mmHg with pH 6.9). She was easily intubated, but mechanical ventilation turned out to be complicated due to the extraordinary resistance of the airway with hyperinflation, auto-PEEP, and hemodynamic instability, all of which made it virtually impossible to achieve the minimum goals of oxygenation and ventilation, yet despite the use of very low oxygen volumes, prolonged expiratory times, and vasopressor therapy with very high doses of noradrenaline. The auscultation confirmed the presence of a very acute inspiratory wheezing at the sternal region. In this context, the patient suffered from two consecutive episodes of cardiac arrest of 10 and 5min duration, respectively with electromechanical dissociation from which she recovered precariously through cardiac massage and adrenaline, followed by very severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia and acidosis (SatO2<50%, PaCO2 above the upper range of the gasometer and pH 6.7), and extreme hemodynamic instability that required vasopressor support at fairly high doses. On suspicion of central airway obstruction (CAO), the medical team decided to conduct one fibrobronchoscopy under circulatory and respiratory assistance using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). This procedure was conducted in the operating room under general anesthesia through open femoro-femoral cannulation and veno-arterial assistance. The fibrobronchoscopy conducted confirmed the almost complete obstruction of the tracheal lumen due to the presence of a white material of mamelonated appearance that was later biopsized obtaining a fibrin-leukocytarian material and mucoid without atypia (Fig. 2). The argon-plasma coagulation electrocautery procedure allowed enough tracheal lumen to facilitate ventilation and improve gas exchange and hemodynamics, leading the team to disconnect the ECMO at the very operating room. On suspicion of an inflammatory process, pulse methylprednisolone therapy (0.5g IV) was started followed by antibiotic therapy. Some 12h later, while the patient was in a more stable hemodynamic and respiratory condition, one thoracoabdominal CT scan was conducted that confirmed the presence of concentric thickening of the tracheal wall and main bronchi, pneumomediastinum, left hydropneumothorax, thoracoabdominal subcutaneous emphysema, and pneumoretroperitoneum (Fig. 3). The left hydropneumothorax was drained and one rigid bronchoscopy was conducted that confirmed less inflammatory material and tracheobronchial occupation. Even so, contemplating the possibility of recurrence, a Y-shaped tracheobronchial tube was implanted. The patient's prognosis was favorable and she experienced a total neurological and cardiorespiratory recovery that allowed the early withdrawal (∼24h) of mechanical ventilation and, eventually, hospital discharge without any sequelae.

All the microbiological studies including bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, viruses and the biopsized material culture tested negative. On suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the serological markers tested positive for ANCA-c and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies. The endoscopic studies showed pancolitis and aphtous ileitis consistent with Crohn's disease, and the biopsies confirmed the presence of “focal active ileitis and diffuse active colitis, with architectural distortion, surface irregularity, and inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria of moderate intensity by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, with neutrophil exocytosis, cryptic abscesses and basal plasmacytosis without granulomas”—all of it consistent with IBD. Today the patient is still on steroids and azathioprine with an acceptable control of the disease.

The CAO is extremely rare, and its diagnosis requires high clinical suspicion, which is difficult in the absence of pathological history.1 It usually kicks in with cough, respiratory failure, and wheezing. At times, it can even simulate a process of asthmatic crisis or acute bronchitis. A simple X-ray can show data of hyperinflation and, in extreme cases, signs of barotrauma due to entrapment. Also, the CT scan can show circumferential or nodular narrowing of the trachea and main bronchi. For diagnostic purposes, the morphology of the flow-volume loop that shows the intrathoracic obstruction in both phases of the respiratory cycle can be useful.2 Bronchoscopy is definitely the diagnostic and therapeutic procedure of choice. In the most serious cases, the use of ECMO can help with the therapeutic rescue and recent medical literature reports isolated cases with high survival rates.3 The type of cannulation and assistance that should be used, whether veno-arterial or veno-venous, depends on the clinical situation we are dealing with. The veno-arterial option allows respiratory and hemodynamic support, and it is the option of choice in patients in shock or who have suffered a cardiac arrest. The veno-venous option should do in situations of hemodynamic stability when gas exchange is an issue.

Extraintestinal manifestations of the IBD could involve almost every organ system, being pulmonary damage the less common of all, with a prevalence >0.5%.4,5 The pathogenic mechanism is still unknown, but it is common to the inflammatory process affecting the intestine.6 It usually occurs years after the diagnosis of IBD, when the disease goes into remission or after one colectomy, being pulmonary damage, exceptional7 and tracheobronchial damage, incidental. Thus, until now only 11 cases of CAO8 have been reported, none of them serious. The data available on these cases show how effective systemic or inhaled steroid treatment really is8; occasionally it will be necessary to resort to bronchoscopic techniques to maintain airway patency.9,10

The case we presented here is unheard of due to its dramatic clinical presentation, to its exceptionality given the CAO occurred at the beginning of the IBD; and because it gave the medical team the opportunity to use ECMO allowing therapeutic rescue in a case whose outcome would have been dramatic in other circumstances. It is the first case ever reported of rescue with ECMO,3 without a prior diagnosis, with impossibility of ventilation, and obstructive shock with cardiac arrest.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez-Romero M, Hernández-Alonso B, García-Polo C, Abraldes-Bechiarelli AJ, Garrino-Fernández A, Gordillo-Brenes A. Obstrucción de la vía aérea central por enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y rescate terapéutico con membrana de oxigenación extracorpórea. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:317–319.