Mechanical ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is related to higher morbidity and mortality rates, and increased costs.1,2 Therefore, different initiatives and measures have been suggested to prevent it.1,2 The Pneumonia Zero Project (PZP) implemented back in 2011 reviewed 35 measures to prevent VAP, and proposed a package of 7 mandatory measures and 3 non-mandatory but highly recommended measures.1 The 7 mandatory measures were: 1) education and training in appropriate airway management; 2) strict hand hygiene with alcohol solutions before airway management; 3) oral hygiene with chlorhexidine (0.12% to 0.2%) every 8 h; 4) control and maintenance of cuff pressure > 20 cmH2O before washing the mouth with chlorhexidine every 8 h; 5) avoidance of 0-degree supine positioning, when possible; 6) promoting procedures and protocols to safely avoid or reduce intubation and/or its duration; and 7) avoidance of elective changes of ventilator circuits, humidifiers, and endotracheal tubes. The highly recommended measures were: 1) selective digestive decontamination (SDD) or selective oropharyngeal decontamination (SOD); 2) continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions; and 3) peri-intubation systemic antibiotics in patients with decreased level of consciousness. The PZP reduced the rate of VAP from 9.83 down to 4.34 for every 1000 days on mechanical ventilation.2 Actually, these rates have remained below 7/1000 days on mechanical ventilation according to annual reports from the National Study on Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (Available online: http://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics).

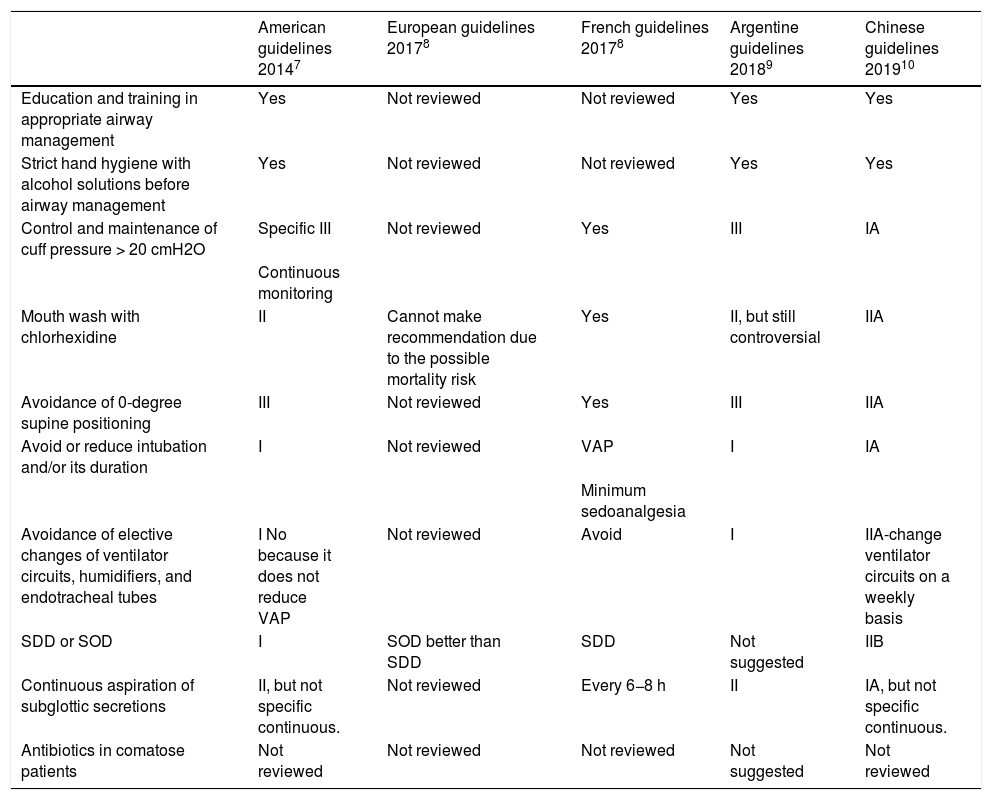

Almost 10 years after the implementation of the PZP new evidence has come to life on several measures. As a matter of fact, some changes could be made to the PZP to keep reducing the current rates of VAP. Also, several clinical practice guidelines on this regard were published by US scientific societies back in 2014,3 Latin American societies in 2017,4 French scientific societies in 2017,5 Argentine societies in 2018,6 and Chinese scientific societies back in 20197 (Table 1).

Recommendations of the different clinical practice guidelines (CPG) after the Pneumonia Zero Project (PZP) on the measures implemented to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia proposed by the PZP.

| American guidelines 20147 | European guidelines 20178 | French guidelines 20178 | Argentine guidelines 20189 | Chinese guidelines 201910 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and training in appropriate airway management | Yes | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Yes | Yes |

| Strict hand hygiene with alcohol solutions before airway management | Yes | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Yes | Yes |

| Control and maintenance of cuff pressure > 20 cmH2O | Specific III | Not reviewed | Yes | III | IA |

| Continuous monitoring | |||||

| Mouth wash with chlorhexidine | II | Cannot make recommendation due to the possible mortality risk | Yes | II, but still controversial | IIA |

| Avoidance of 0-degree supine positioning | III | Not reviewed | Yes | III | IIA |

| Avoid or reduce intubation and/or its duration | I | Not reviewed | VAP | I | IA |

| Minimum sedoanalgesia | |||||

| Avoidance of elective changes of ventilator circuits, humidifiers, and endotracheal tubes | I No because it does not reduce VAP | Not reviewed | Avoid | I | IIA-change ventilator circuits on a weekly basis |

| SDD or SOD | I | SOD better than SDD | SDD | Not suggested | IIB |

| Continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions | II, but not specific continuous. | Not reviewed | Every 6−8 h | II | IA, but not specific continuous. |

| Antibiotics in comatose patients | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Not suggested | Not reviewed |

SDD, selective digestive decontamination; SOD, selective oropharyngeal decontamination.

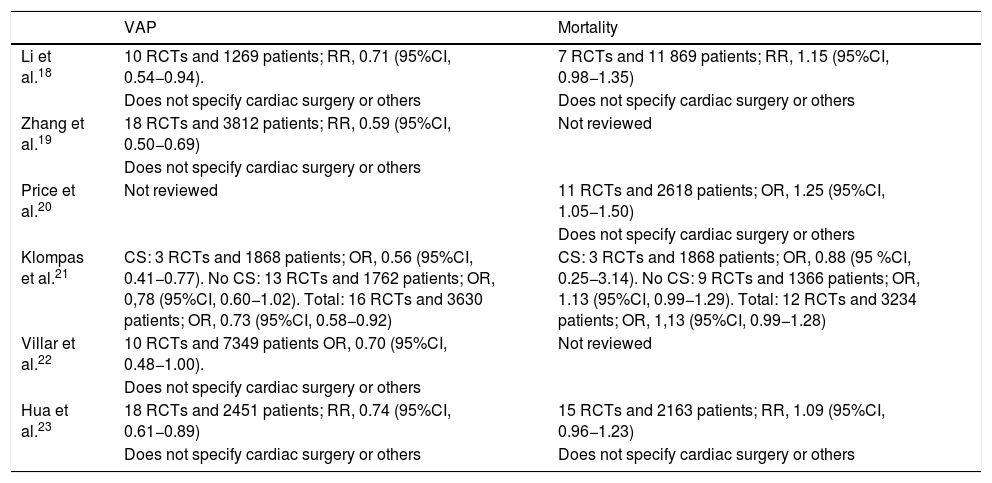

Regarding most mandatory measures of the PZP, there are no new studies suggesting their withdrawal. Also, these are not hard to implement. However, regarding mouth washes with chlorhexidine, several meta-analyses have been published that confirm that these not only reduce VAP,8 but also increase mortality non-significantly, especially in patients not admitted due to cardiac surgery (Table 2). This possible deleterious effect may be associated with the existence of microaspirations of chlorhexidine that can cause pulmonary damage. After analyzing these meta-analyses, the “Safety projects in critically ill patients” counselling board of the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs, and Social Welfare decided to move it from mandatory to non-mandatory recommendation in a meeting held back in June 2018 (https://semicyuc.org/2018/07/recomendacion-de-lavado-oral-con-clorhexidina-en-patients-ventilaSOD).

Meta-analyses conducted after the Pneumonia Zero Project (PZP) on mouth hygiene with chlorhexidine vs placebo.

| VAP | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|

| Li et al.18 | 10 RCTs and 1269 patients; RR, 0.71 (95%CI, 0.54−0.94). | 7 RCTs and 11 869 patients; RR, 1.15 (95%CI, 0.98−1.35) |

| Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | |

| Zhang et al.19 | 18 RCTs and 3812 patients; RR, 0.59 (95%CI, 0.50−0.69) | Not reviewed |

| Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | ||

| Price et al.20 | Not reviewed | 11 RCTs and 2618 patients; OR, 1.25 (95%CI, 1.05−1.50) |

| Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | ||

| Klompas et al.21 | CS: 3 RCTs and 1868 patients; OR, 0.56 (95%CI, 0.41−0.77). No CS: 13 RCTs and 1762 patients; OR, 0,78 (95%CI, 0.60−1.02). Total: 16 RCTs and 3630 patients; OR, 0.73 (95%CI, 0.58−0.92) | CS: 3 RCTs and 1868 patients; OR, 0.88 (95 %CI, 0.25−3.14). No CS: 9 RCTs and 1366 patients; OR, 1.13 (95%CI, 0.99−1.29). Total: 12 RCTs and 3234 patients; OR, 1,13 (95%CI, 0.99−1.28) |

| Villar et al.22 | 10 RCTs and 7349 patients OR, 0.70 (95%CI, 0.48−1.00). | Not reviewed |

| Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | ||

| Hua et al.23 | 18 RCTs and 2451 patients; RR, 0.74 (95%CI, 0.61−0.89) | 15 RCTs and 2163 patients; RR, 1.09 (95%CI, 0.96−1.23) |

| Does not specify cardiac surgery or others | Does not specify cardiac surgery or others |

CS, cardiac surgery; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RCT, randomized clinical trial; RR, relative risk; VAP, to prevent mechanical ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Around this time, a retrospective study including 82 274 patients was published that confirmed a higher mortality risk in a group of 11 133 patients treated with mouth wash with chlorhexidine.9 Mouth wash with chlorhexidine was associated with a higher mortality rate among the 69 208 patients who were not admitted to the ICU and with a lower mortality rate in the 2847 patients on mechanical ventilation ≤96 h. However, no differences were reported in the mortality rate of the group of 9316 patients admitted to the ICU without mechanical ventilation or in the group of 903 patients on mechanical ventilation >96 h (still, there was a tendency towards a higher mortality rate with the use of chlorhexidine).

Highly recommended non-mandatory measures of the Pneumonia Zero ProgramRegarding SDD or SOD, a meta-analysis of 6 randomized clinical trials (RCT) and 17 884 patients was published back in 2018. It confirmed a lower in-hospital mortality rate associated with the use of these types of decontamination. As a matter fact, it was lower with SDD compared to SOD. Regarding the aspiration of subglottic secretions (ASS), a meta-analysis of 20 RCTs and 3544 patients published in 2016 confirmed the lower rate of VAP reported.

Regarding peri-intubation systemic antibiotics in patients with decreased level of consciousness, a review published back in 2017 found 4 studies (2 RCTs and 2 observational studies) including a total of 1507 patients (1240 patients from 1 observational study). In all of them, the rate of VAP dropped significantly.10 In each study, different antibiotics were administered to different patients (from Glasgow Coma Scale ≤ 12 until cardiorespiratory arrest), different antibiotics were used (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone), throughout different durations too (from a single dose to 3-day courses). In a RCT published in 2019, 194 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrests treated with hypothermia (89.6 °F to 93.2 ° F for 24 h–36 h) were randomized to receive IV amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (dose of 1 g and 200 mg, respectively every 8 h for 2 days) or placebo. The treatment group had a lower rate of early-onset VAP, but no differences in the 28-day mortality rate were reported.11 Currently, one ongoing randomized clinical trial (RCT) is studying the administration of a single dose of 2 g of ceftriaxone in patients with Glasgow Coma Scale ≤ 12 (NCT02265406). To this date, there is no scientific evidence to say what antibiotics and dose should be used, in what kind of patients or what the duration of these antibiotics should be. However, it seems reasonable to think that amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefuroxime or ceftriaxone for 2–3 days in intubated patients with Glasgow Coma Scale ≤ 8 should be recommended

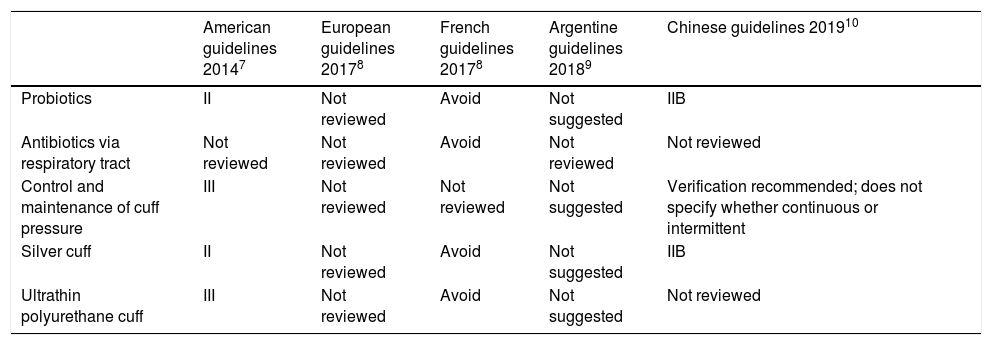

Optional unselected measures in the Pneumonia Zero Project (Table 3)Regarding the administration of probiotics, a meta-analysis of 8 RCTs and 1083 patients published in 2016 concluded that these were associated with a lower rate of VAP.12 Currently, the RCT is ongoing (NCT02462590).

Recommendations of the different clinical practice guidelines (CPG) after the Pneumonia Zero Project (PZP) on the measures implemented to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia not proposed by the PZP.

| American guidelines 20147 | European guidelines 20178 | French guidelines 20178 | Argentine guidelines 20189 | Chinese guidelines 201910 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | II | Not reviewed | Avoid | Not suggested | IIB |

| Antibiotics via respiratory tract | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Avoid | Not reviewed | Not reviewed |

| Control and maintenance of cuff pressure | III | Not reviewed | Not reviewed | Not suggested | Verification recommended; does not specify whether continuous or intermittent |

| Silver cuff | II | Not reviewed | Avoid | Not suggested | IIB |

| Ultrathin polyurethane cuff | III | Not reviewed | Avoid | Not suggested | Not reviewed |

Regarding the use of antibiotics via respiratory tract a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs and 1158 patients published in 2018 confirmed a lower rate of VAP. However, no differences in the mortality rate in the ICU setting were reported.13 In the sub-analysis of the administration of nebulized antibiotics of 3 RCTs and 313 patients a significant drop in the rate of VAP was seen. However, the sub-analysis of the administration of instilled antibiotics of 3 RCTs and 845 patients only found a non-significant reduction of the rate of VAP.

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs and 543 patients, published back in 2015, concluded that the continuous control and maintenance of cuff pressure was associated with a lower risk of VAP. However, no differences were reported in the duration of mechanical ventilation, the ICU stay or in the mortality rate.14 Regarding the use of silver-impregnated cuffs, a RCT published in 2008 that included 1509 patients found a lower rate of VAP.15

A review published back in 2016 on endotracheal tubes with ultra-thin polyurethane cuffs and VAP found 3 studies and 708 patients (a significant reduction was reported in 2 RCTs and a non-significant reduction in 1 RCT). However, no differences were reported in the duration of mechanical ventilation, the ICU stay or in the mortality rate.16

Possibly, the implementation of combined measures may be more effective compared to the implementation of isolated measures. A study found a lower rate of VAP when continuous control and maintenance of cuff pressure or ASS were implemented. Also, the rate of VAP was reduced even further after the implementation of 2 measures combined.17

Plan to reduce the current rates of mechanical ventilator-associated pneumoniaIt has been suggested to spare SDD, SOD, and ASS as non-mandatory highly recommended measures following the results of meta-analyses including a large number of patients from RCTs. Also, optional measures like the ones proposed in observational studies or meta-analyses of few patients have been suggested. This group of optional measures would include the administration of peri-intubation systemic antibiotics in patients with decreased level of consciousness (this measure is currently considered non-mandatory but highly recommended by the PZP), mouth wash with chlorhexidine (since June 2018, the “Safety projects in critically ill patients” counselling board of the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs, and Social Welfare decided to move it from mandatory to non-mandatory recommendation), and other measures unforeseen by the PZP (probiotics, antibiotics via respiratory tract, continuous control and maintenance of cuff pressure, silver-impregnated cuffs, endotracheal tubes with ultra-thin polyurethane cuffs).

In ICUs with incidence rates of VAP > 7 episodes per 1000 days on mechanical ventilation—the quality standard proposed by SEMICYUC back in 2017 (https://www.bing.com/searchPC=WCUG&FORM=WCUGDF&q=indicadoresdecalidad2017_semicyuc_spa-1.pdf)—internal audits should be conducted to determine whether measures are being implemented correctly, and whether the plan can be improved. If there is no room for improvement and everything has been corrected, more measures than the ones already implemented should be used. For the sake of efficiency, they should be implemented individually and not combined or at the same time. Either one of the 2 non-mandatory but highly recommended measures could be implemented here (SDD/SOD or ASS). It their primary goal is not achieved, the other non-mandatory but highly recommended measure could be implemented followed by the gradual implementation of optional measures.

Conflicts of interestNone reported.

Please cite this article as: Lorente L. Reducir las tasas actuales de neumonía asociada a ventilación mecánica tras la implantación del programa Neumonía Zero: este es el reto. Med Intensiva. 2021;45:501–505.