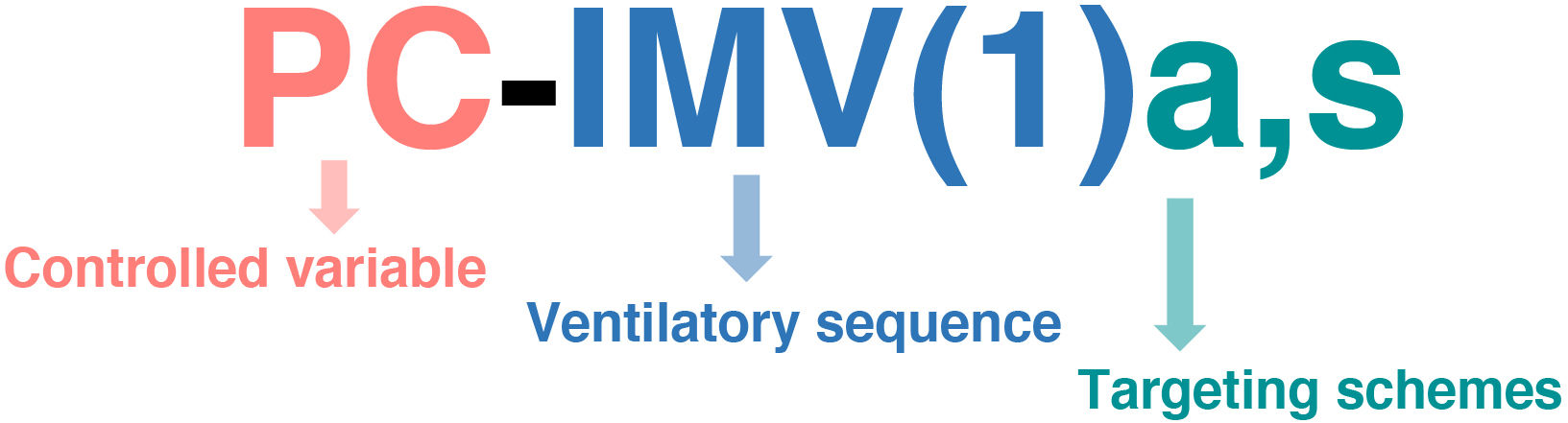

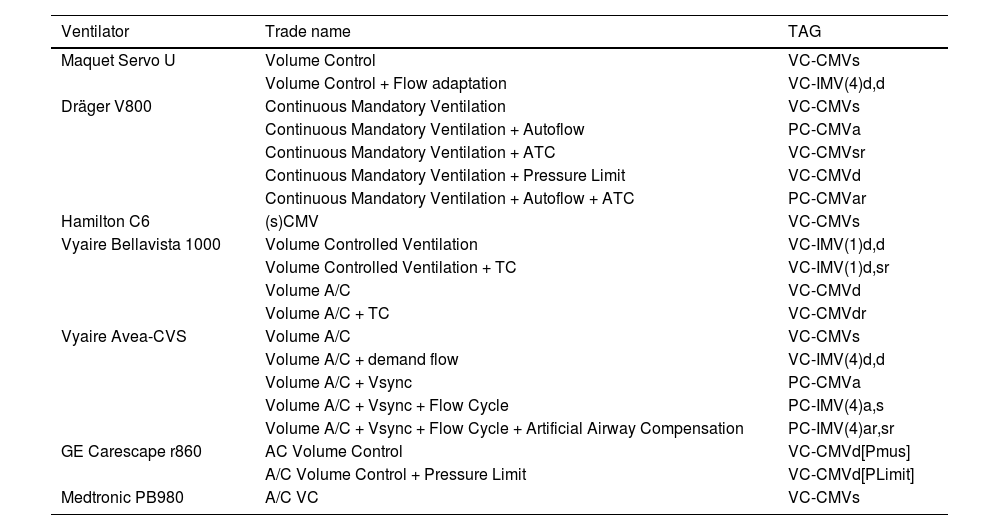

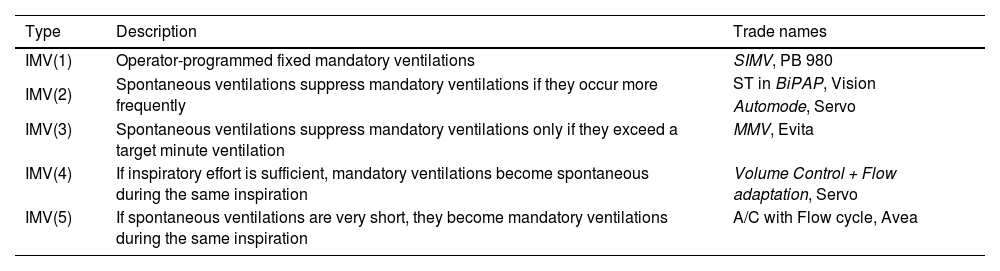

The rapid technological development of mechanical ventilation has resulted in increasingly complex modes, advanced monitoring capabilities and the incorporation of artificial intelligence. However, manufacturers have created a multitude of trade names, which has generated a great deal of confusion in their understanding, handling and application. This problem is exacerbated in Spanish-speaking countries due to inconsistencies in translations and variability in nomenclature between regions. This manuscript aims to provide an updated review of the taxonomic classification of ventilatory modes in order to promote standardization of terminology, especially in the Spanish-speaking clinical context, and includes changes in the taxonomy and manner of labeling modes of mechanical ventilation. This review focuses on invasive mechanical ventilation of the adult critically ill patient, although the taxonomy is also applicable to all ventilation modalities, including noninvasive, high-frequency, pediatric, and even home ventilation.

El rápido desarrollo tecnológico de la ventilación mecánica ha dado lugar a modos cada vez más complejos, capacidades avanzadas de monitoreo y la incorporación de inteligencia artificial. Sin embargo, los fabricantes han creado una multitud de nombres comerciales, lo que ha generado una gran confusión en su comprensión, manejo y aplicación. Este problema se agrava en los países de habla hispana debido a las inconsistencias en las traducciones y la variabilidad de la nomenclatura entre regiones. Este manuscrito tiene como objetivo proporcionar una revisión actualizada de la clasificación taxonómica de los modos ventilatorios con el fin de promover la estandarización de la terminología, especialmente en el contexto clínico de habla hispana, e incluye cambios en la taxonomía y la manera de etiquetar modos de ventilación mecánica. Esta revisión se centra en la ventilación mecánica invasiva del paciente crítico adulto, aunque la taxonomía también es aplicable a todas las modalidades de ventilación, incluyendo la ventilación no invasiva, de alta frecuencia, pediátrica e incluso domiciliaria.

Article

Go to the members area of the website of the SEMICYUC (www.semicyuc.org )and click the link to the magazine.