The Expert Committee on Critical Care Medicine at Altitude of the Pan American and Iberian Federation of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care detected a lack of terms defining this critical care medicine, as well as a lack of standardization in the approach to these patients. These shortcomings can lead to errors in management, for example, in critically ill patients at risk of death who require oxygen therapy, whether invasive or non-invasively.

The objective of the Expert Committee was to develop an international consensus that would standardize terminology and establish key definitions and recommendations for the care of critically ill patients at altitude. This document includes five important definitions, four recommendations related to the management of acute respiratory failure at altitude, and a series of considerations for future research. It also establishes specific criteria that differentiate it from the traditional approach used at sea level.

El Comité de Expertos en Medicina Crítica en la Altitud de la Federación Panamericana e Ibérica de Medicina Crítica y Terapia Intensiva, detectó una falta de términos que definieran esta medicina crítica, así como una falta de estandarización en el abordaje de estos pacientes. Estas carencias pueden llevar a errores en su manejo como, por ejemplo, en pacientes críticos en riesgo de muerte que requieren terapia con oxigeno ya sea invasivo como no invasivo.

El objetivo del Comité de Expertos ha sido desarrollar un consenso internacional que uniformara la terminología y estableciera las definiciones y recomendaciones claves para la atención del paciente crítico en altitud. Este documento, recoge cinco definiciones importantes, cuatro recomendaciones relacionadas con el manejo de la insuficiencia respiratoria aguda en la altitud y una serie de consideraciones sobre futuras investigaciones; y establece unos criterios específicos que lo diferencian del enfoque tradicional utilizado al nivel del mar.

Altitude should be expressed in meters above sea level (masl). Living in a high-altitude area poses significant challenges for its inhabitants and for individuals who climb to altitudes above 2,500 masl. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a transcription factor that regulates the cellular response to hypoxia. In hypoxic situations, it plays a fundamental role in oxygen homeostasis by facilitating oxygen delivery to all body tissues.1 Genetic activation triggered by hypoxia facilitates adaptation in individuals living in high-altitude zones. It facilitates acclimatization during short stays and guarantees normal metabolic functioning2,3 under environmental conditions that decrease arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) and oxygen saturation (SaO2).4

Acclimatization and adaptation mechanisms can significantly modify respiratory, cardiovascular, hematological, and metabolic physiology,5 directly affecting the diagnosis and management of critical illness. In this context, there is a need to establish specific criteria for managing critical patients at high altitudes that differ from the traditional approach used at sea level. However, the available medical literature on critical care medicine at altitude is limited. In many cases, it is inconsistent in its use of terms, diagnostic criteria, and physiological reference parameters. This lack of standardization can lead to errors in assessment and treatment. For example, in critically ill patients at risk of death who require both invasive and noninvasive oxygen therapy.6

Aware of this problem, the Pan-American and Iberian Federation of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care (Federación Panamericana e Ibérica de Medicina Crítica y Terapia Intensiva [FEPIMCTI]), constituted the Expert Committee in Critical Care Medicine at Altitude to develop a consensus establishing key definitions and recommendations for critically ill patient care at high altitude. The result of the First International Consensus on Critical Care Medicine at Altitude aims to standardize terminology and establish the foundations for managing critically ill patients at altitude through a series of definitions and recommendations. As many Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in Latin America have limited resources,7,8 the recommendations can be adapted to the available resources.

Materials and methodsThe Committee on High Altitude Medicine of the Pan-American and Iberian Federation of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care (FEPIMCTI) convened this consensus with the aim of establishing definitions, clinical criteria, and specific recommendations for the management of critically ill patients in high-altitude environments. Before beginning the process, formal endorsement from the FEPIMCTI Board of Directors was requested and obtained to ensure institutional and academic support consensus developement.

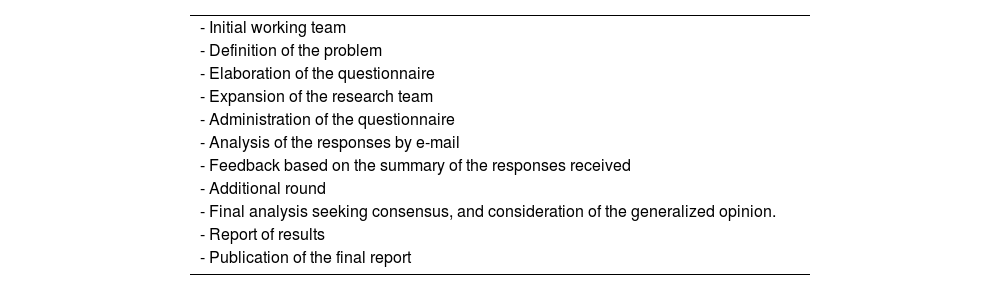

The consensus was developed using the Delphi ACCORD tool, which is a variant of the Delphi technique that focuses on achieving consensus among experts on a specific topic through multiple rounds of questionnaires and feedback. This iterative process allows for the convergence of different perspectives.

Initial working teamA coordination group formed by three FEPIMCTI intensivists with extensive experience in critical care medicine at high altitudes was formed to lead all the methodological phases of the project.

Bibliographic reviewPrior to the consensus, a group of critical care medicine specialists who work at high altitudes searched for available information in different domains of intensive care medicine at high altitudes. Rather than postulating a specific question, they explored the definitions and variables used in the different publications on the subject. They searched PubMed®, Embase®, Scielo®, Bireme®, Latindex®, and Google Scholar® databases for information and explored medRxiv for gray literature. The research strategy included the terms “intensive care medicine”, “altitude”, “hypobaric hypoxia”, “arterial blood gases”, and “acute respiratory failure”. The database search identified 218 articles, in Spanish or English, related to the terms of interest. After critically analyzing these articles, 68 publications were finally identified as the basis for defining the problem and building consensus.6

Definition of the problemIt was observed that different terms were used in relation to the posed problem, resulting in highly diverse outcomes. Therefore, the decision was made to focus this first consensus on standardizing the terms to be used in publications on critical care medicine at high altitudes and the concepts of acute respiratory failure (ARF) at high altitudes.

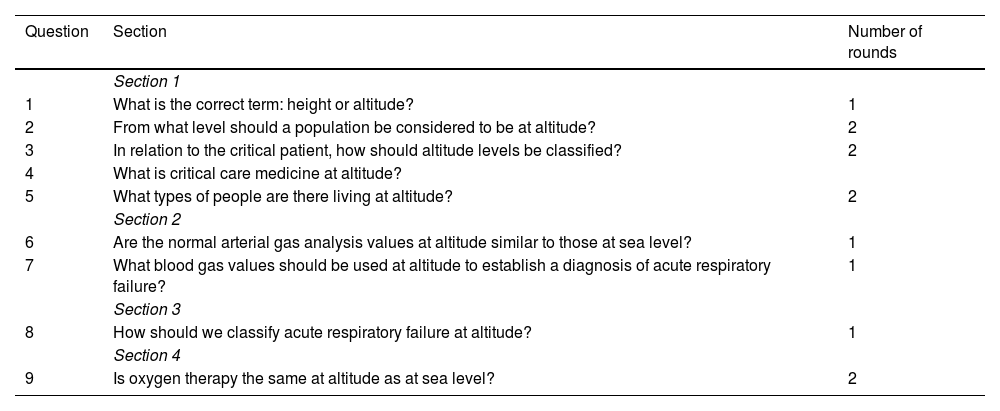

Consensus developmentOnce the problem was defined, a 9-question questionnaire was drafted (Table 1). Subsequently, the research team was expanded to include 17 experts from 6 different countries, primarily from Latin America. Experts were defined as individuals with knowledge and experience in the subject under study. After forming the research team, the coordinating group sent an email to each expert with a link to an anonymous survey. The Delphi ACCORD tool was then implemented (Table 2). The criterion for reaching an agreement on the question was considered met when the percentage was 75% or higher.

Questions formulated for the consensus of the FEPIMCTI Altitude Medicine Committee, distribution by sections, and number of rounds of approval per question.

| Question | Section | Number of rounds |

|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | ||

| 1 | What is the correct term: height or altitude? | 1 |

| 2 | From what level should a population be considered to be at altitude? | 2 |

| 3 | In relation to the critical patient, how should altitude levels be classified? | 2 |

| 4 | What is critical care medicine at altitude? | |

| 5 | What types of people are there living at altitude? | 2 |

| Section 2 | ||

| 6 | Are the normal arterial gas analysis values at altitude similar to those at sea level? | 1 |

| 7 | What blood gas values should be used at altitude to establish a diagnosis of acute respiratory failure? | 1 |

| Section 3 | ||

| 8 | How should we classify acute respiratory failure at altitude? | 1 |

| Section 4 | ||

| 9 | Is oxygen therapy the same at altitude as at sea level? | 2 |

FEPIMCTI: Pan-American and Iberian Federation of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care.

Essential elements of the Delphi ACCORD methodology.

| - Initial working team |

| - Definition of the problem |

| - Elaboration of the questionnaire |

| - Expansion of the research team |

| - Administration of the questionnaire |

| - Analysis of the responses by e-mail |

| - Feedback based on the summary of the responses received |

| - Additional round |

| - Final analysis seeking consensus, and consideration of the generalized opinion. |

| - Report of results |

| - Publication of the final report |

The questions were divided into four sections. Initially, the first section consisted of the first three questions. However, before sending it to the experts, two more questions were added, bringing the total number of questions in the section to five. Table 1 shows the questions that formed each section and the approval rounds. Participation in the rounds was consistently above 80%.

Once the work was completed, the coordinating group wrote the final draft and sent it to each expert for contributions or suggestions over a 20-day period. After this time, the final draft was prepared for publication.

ResultsThe coordinating group began its work in September 2023. The full group of experts was formed in December. In January 2024, the first section of the questionnaire was sent to each of the experts, who had 20 days to respond. The same approach was used for the remaining three sections. When discrepancies arose, a summary report was prepared with the possible responses, and the experts were given 15 days to reply. All the rounds were completed by the end of June. They received the draft text in September, and the final draft was approved in October 2024. Before submitting the text for publication, all the authors acknowledged their authorship and signed the conflicts of interest document. No deviation from the study protocol was necessary.

Critical care medicine at altitude: definitionsJustification: Although there are many publications related to high-altitude medicine, they usually focus on mountain physiology and diseases related to acclimatization and adaptation. Numerous publications and specialized journals exist on critical care medicine, yet there are practically no specific publications on critical care medicine at altitude. In the literature, the terms “height” and “altitude” are often used interchangeably.

An estimated 385 million people worldwide live at an elevation of over 1,500 meters above sea level (masl), with 140 million living above 2,500 masl. Of these, 80 million live in Asia and 35 million live in the Andes.6,9 In Latin America, 32 ICUs are located between 2,500 and 4,380 masl.7 To ensure a uniform standard of care, several concepts related to critical care medicine at altitude need to be defined.10

Which is the correct term: height or altitude?It is frequent to conceptually confuse the terms “height” and “altitude”, which is a commonly neglected error. Correcting this error is essential to ensure the greatest possible understanding and accuracy in scientific communication. Height and altitude are two distinct concepts. Height is the vertical distance from a body to the Earth's surface or ground. For example, the height of a person or the height of a building is measured in centimeters and/or meters. Altitude, on the other hand, is the vertical elevation above sea level and is measured in meters above sea level (masl). As we can see, they are two very different things.

According to the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language (Real Academia de la Lengua Española), the correct term is “altitud” (altitude).6,11

From what level should a population be considered to be at altitude?Living at an altitude generates adaptations in people. Many cutoff levels have been proposed for determining which populations exhibit these adaptations. One proposal is an altitude of 2,100 masl because oxyhemoglobin saturation begins to decrease drastically at this level.12 Similarly, an altitude of 2,500 masl has been suggested because symptoms appear at this altitude during the ascent.13 However, it has been seen that the first adaptations and effects on physical performance derived from the progressive decrease in barometric pressure (BP) following the ascent to altitude are observed from 1,500 masl.9,14 Although no symptoms are evident, changes can already be noted in the arterial gas analyses.15,16 In addition, residents at these altitudes are characterized by a smaller body size, with enlarged ribs, improved oxygen delivery under hypoxic conditions, and adjustments in oxygen utilization and metabolism. Acute and chronic hypoxia prevailing in these regions can trigger various disease conditions by stimulating hypoxia-inducible factors, enhancing inflammatory responses, and altering mitochondrial function.17

We consider a population to be affected by altitude when it resides at an elevation of 1,500 masl or higher. Thus, critical care medicine at high altitudes is responsible for the management of critically ill patients in communities residing at an altitude of 1,500 masl or higher, which represents 2% of the world's population.

How should altitude levels be classified in relation to critical patients?There are multiple ways of classifying altitude,9,18,19 several of which take into account the ascent of non-residents for sporting activities, intermittent work, etc. One classification system categorizes altitude as follows: low (below 1,500 masl), medium (1,500 to 2,500 masl), high (2,500 to 3,500 masl), very high (3,500 to 5,800 masl), extreme (above 5,800 masl), and death zone (above 8,000 masl).18 Other classifications are poorly fragmented with excessively wide boundaries, which do not allow for an adequate evaluation of the adaptive differences according to altitude levels.14 Therefore, considering that adaptive processes begin at 1,500 masl and that the ICUs at the highest altitude in the world are those located in Cerro de Pasco, Peru, at 4,380 masl and El Alto, Bolivia, at 4,150 masl,6,20 it was necessary to establish a useful, practical scale to facilitate the management of critical patients at altitude.

From a practical point of view, we classify altitude using the Barry and Pollard scale19 as follows:

- •

Medium altitude: from 1,500 to 2,500 masl.

- •

High altitude: from 2,500 to 3,500 masl.

- •

Very high altitude: from 3,500 to 5,800 masl.

As explained in the section “From what level should a population be considered to be at altitude?”, critical care medicine at altitude involves managing critically ill patients residing at an altitude of 1,500 masl or higher. At high altitudes, hypobaric hypoxia can facilitate correct acclimatization through HIF-1. However, it can also trigger acute mountain sickness that, in advanced stages, leads to altitude cerebral edema and can even result in death. Additionally, it can favor chronic adaptation to altitude or result in subacute mountain sickness (altitude pulmonary hypertension) and chronic mountain sickness (Monge's disease).21,22

Critical care medicine at altitude is a branch of intensive care medicine dealing with the management of critically ill patients at altitudes above 1,500 masl who are affected by hypobaric hypoxia. This hypoxia can trigger the following6,14,21,23:

- •

Inherent altitude disorders due to ascent, such as severe acute altitude sickness associated with pulmonary edema and cerebral edema, as well as the exacerbation of chronic comorbidities in non-acclimatized or insufficiently acclimatized individuals.

- •

Complications of acute critical disorders in altitude-dwelling individuals, such as acute respiratory failure, are affected by chronic adaptation to altitude in terms of diagnosis and management.

A great diversity of population types is found at high altitudes. These types can be classified as follows6,24–26:

- •

According to origin:

- ◦

Native: A person born and raised at a high altitude, who has developed natural acclimatization to hypobaric conditions. These individuals usually have physiological adaptations that allow them to live, reproduce, and function efficiently in high-altitude environments.

- ◦

Non-native or immigrant: A person not born at altitude and who ascends to altitude.

- ◦

- •

According to the duration of residence:

- ◦

Resident: A person who has lived at an altitude above 1,500 masl for at least one year. Initially, these people may experience some of the effects of altitude, but over time, they become acclimatized.

–Among residents, we have:

- ◦

Permanent residents: Those who have lived at high altitudes for at least one year.

Transient residents: Those who live at high altitudes intermittently for at least two weeks per month for a continuous year.

- ◦

Non-resident or visitor: People who live at lower altitudes and visit or stay in high-altitude areas for limited periods or stay less than one year. They may be at a higher risk for altitude sickness due to a lack of prior acclimatization.

- ◦

Justification: At altitudes above 1,500 masl, variables such as barometric pressure, inspired oxygen pressure (IOP2), PaO2, and consequently SaO2 are decreased. The higher the altitude, the greater the decrease.7,8

Do arterial gases at high altitudes have an impact on pulmonary function?At high altitudes, we observe the following in relation to the arterial gas values at sea level:

- •

A decrease in PaO2, which is inversely proportional to the increase in altitude and directly proportional to the decrease in barometric pressure.

- •

A drastic decrease from 1,500 masl in PaCO2 to average values of 30mmHg.

- •

A decrease in bicarbonate (HCO3) and SaO2.

There is no impact on pulmonary function because:

- •

The pH value is within normal ranges since the resident at high altitude has managed to reestablish an adequate internal environment to maintain optimal cellular functioning despite the previously mentioned changes.

- •

Lactate maintains normal values (<2mmol/l). Despite the decrease in PaO2, adequate tissue perfusion is maintained.

- •

The alveolar-alveolar gradient is below 20mmHg, indicating high gas exchange efficiency.6,8,15,16,27–31

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is the inability to adequately exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide between the bloodstream and ambient air, which results in the body not receiving enough oxygen. In a previously healthy lung, ARF can develop in minutes, hours, or days. While it is not possible to specify exact values for different clinical situations, conventionally, the following limits are considered to define ARF: PaO2 < 60mmHg or SaO2 < 90% and/or aPaCO2 > 45−50mmHg when breathing room air and awake.32 At altitude, diagnosing ARF using sea-level criteria is incorrect.6–8,30,32 Nevertheless, studies on blood gas values that should be considered normal at these altitudes are very scarce. From 3,000 masl, PaO2 values are close to or below 60mmHg.6,8,29,33

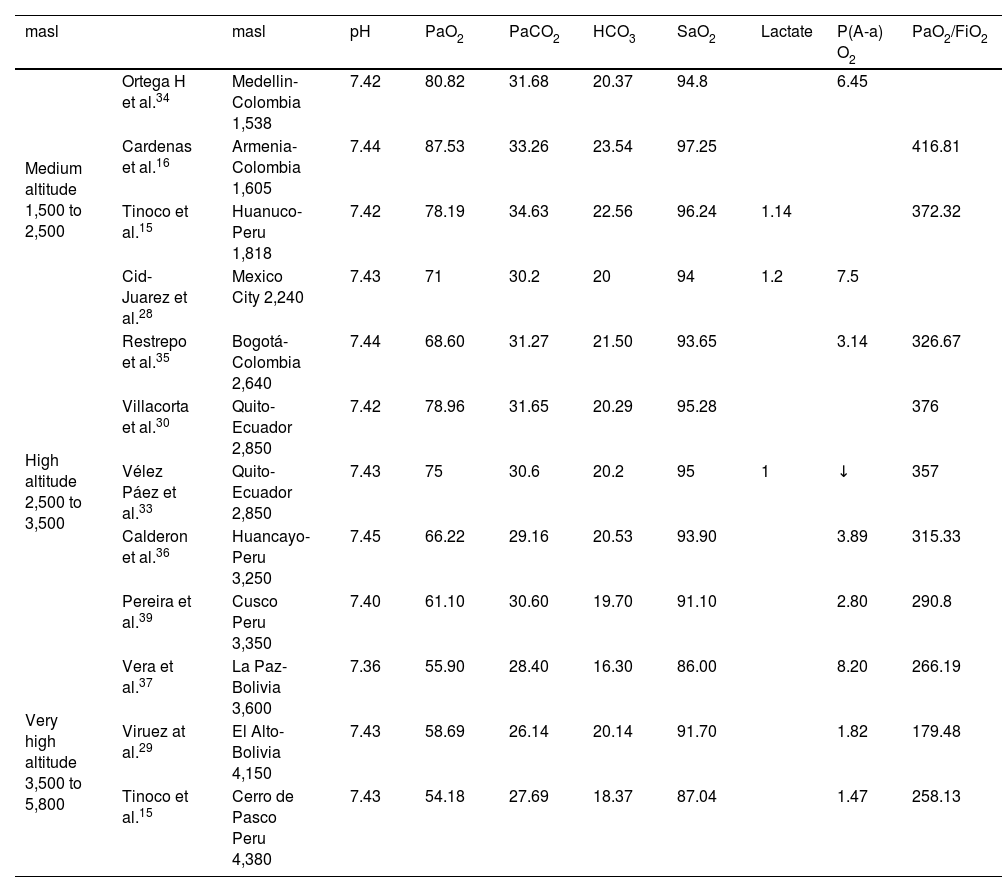

Normal blood gas values at high altitudes differ from those at sea level because they are affected by changes in barometric pressure and its impact on the gradual decrease in atmospheric oxygen pressure (IOP2), alveolar oxygen pressure, and PaO2 (Table 3).15,16,28–30,34–37,39 At high altitudes, gasometric diagnoses depend on the normal values determined by the level of altitude. Therefore, it is necessary to know the gasometric reference ranges considered normal at different altitudes.

Gasometric values of healthy residents reported in South American cities at altitude.

| masl | masl | pH | PaO2 | PaCO2 | HCO3 | SaO2 | Lactate | P(A-a) O2 | PaO2/FiO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium altitude 1,500 to 2,500 | Ortega H et al.34 | Medellin-Colombia 1,538 | 7.42 | 80.82 | 31.68 | 20.37 | 94.8 | 6.45 | ||

| Cardenas et al.16 | Armenia-Colombia 1,605 | 7.44 | 87.53 | 33.26 | 23.54 | 97.25 | 416.81 | |||

| Tinoco et al.15 | Huanuco-Peru 1,818 | 7.42 | 78.19 | 34.63 | 22.56 | 96.24 | 1.14 | 372.32 | ||

| Cid-Juarez et al.28 | Mexico City 2,240 | 7.43 | 71 | 30.2 | 20 | 94 | 1.2 | 7.5 | ||

| High altitude 2,500 to 3,500 | Restrepo et al.35 | Bogotá-Colombia 2,640 | 7.44 | 68.60 | 31.27 | 21.50 | 93.65 | 3.14 | 326.67 | |

| Villacorta et al.30 | Quito-Ecuador 2,850 | 7.42 | 78.96 | 31.65 | 20.29 | 95.28 | 376 | |||

| Vélez Páez et al.33 | Quito-Ecuador 2,850 | 7.43 | 75 | 30.6 | 20.2 | 95 | 1 | ↓ | 357 | |

| Calderon et al.36 | Huancayo-Peru 3,250 | 7.45 | 66.22 | 29.16 | 20.53 | 93.90 | 3.89 | 315.33 | ||

| Pereira et al.39 | Cusco Peru 3,350 | 7.40 | 61.10 | 30.60 | 19.70 | 91.10 | 2.80 | 290.8 | ||

| Very high altitude 3,500 to 5,800 | Vera et al.37 | La Paz-Bolivia 3,600 | 7.36 | 55.90 | 28.40 | 16.30 | 86.00 | 8.20 | 266.19 | |

| Viruez at al.29 | El Alto-Bolivia 4,150 | 7.43 | 58.69 | 26.14 | 20.14 | 91.70 | 1.82 | 179.48 | ||

| Tinoco et al.15 | Cerro de Pasco Peru 4,380 | 7.43 | 54.18 | 27.69 | 18.37 | 87.04 | 1.47 | 258.13 |

FiO2: inspired fraction of oxygen; HCO3: bicarbonate; masl: meters above sea level; P(A-a) O2: alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide pressure; PaO2: arterial oxygen pressure; pH: potential of hydrogen; SatO2: arterial oxygen saturation.

At sea level, the normal PaO2 value is 80−97mmHg. At sea level, hypoxemia is determined by PaO2<80mmHg. It is classified as mild if the value is 71−80mmHg; moderate: 61−70mmHg; severe: 45−60mmHg; or critical: < 45 mmHg.6 According to these values, people at medium altitudes would have mild hypoxemia, people at high altitudes would have moderate hypoxemia, and people at very high altitudes would have severe hypoxemia (respiratory failure). However, this is incorrect.6,8,38

Acute respiratory failure should be classified based on the relationship between the normal PaO2 values according to altitude, the clinical presentation of respiratory failure, the lactate levels, and cardiorespiratory function, as many patients remain “functional with blood gas values lower than the recommended cut-off levels”.

Is oxygen therapy the same at high altitudes as it is at sea level?The criteria for initiating oxygen therapy are different at altitude. The oxygenation goals are also different. Levels of hypoxemia and hypocapnia depend on altitude, as do levels of hyperoxia and hypercapnia.6–8,28,39–41 Experience acquired during the COVID-19 pandemic regarding oxygenation and ventilation has led to suggestions and oxygenation goals that compensate for the lack of recommendations and evidence.7,40,41

It is recommended that oxygen therapy at high altitudes be initiated when:

- •

At medium altitudes (1,500 to 2,500 masl): If SaO2 < 90%.

- •

At high altitudes (2,500 to 3,500 masl): If SaO2 < 88%.

- •

At very high altitudes (3,500 to 4,380 masl): If SaO2 < 86%.

The oxygenation goals at altitude are:

- •

At medium altitudes (1,500 to 2,500 masl): SaO2 92% and PaO2 75mmHg.

- •

At high altitudes (2,500 to 3,500 masl): SaO2 90% and PaO2 70mmHg.

- •

At very high altitudes (3,500 to 4,380 masl): SaO2 88% and PaO2 60mmHg.

Hyperoxia should be avoided. It is advisable to avoid the following SaO2 levels:

- •

Medium altitudes: SaO2>96%.

- •

High altitudes: SaO2>94%.

- •

Very high altitudes: SaO2>92%.

Hypercapnia should be avoided:

- •

Maintain PaCO2 at its normal gasometric value relative to the altitude. The mean PaCO2 value at altitude is 30mmHg.

Critical care medicine at altitude is defined as a branch of intensive care medicine dealing with the management of critically ill patients residing at altitudes above 1,500 masl. All patients are affected by hypobaric hypoxia due to altitude, whether they are native or non-native residents. This condition is one of the greatest challenges in intensive care medicine and affects approximately 2% of the world's population.9 Addressing the profound hypoxia, the physiological changes, and the disease conditions associated with high altitudes requires a thorough understanding of the biological mechanisms and adaptive responses of the human body, as well as extensive clinical experience and teamwork in environments with limited resources.7,8

This consensus has established a series of suggestions that must be validated by new analytical and experimental studies. However, it has also opened up new paths for future research.

Recent publications have found differences in PaO2 and hematocrit when comparing these values in arterial blood gases studied between premenopausal and menopausal women. In the first group, PaO2 is higher than in the second group, while hemoglobin is lower. With menopause, these values equalize between the two groups, becoming similar to those in men. These changes, which are reflected in very few publications, seem to be related to testosterone and the ovarian hormones.31,33,38 Though they should be viewed with caution, they open a new avenue of research.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is one of the greatest challenges that most intensivists face almost daily. Its clinical definition has evolved over time, most recently resulting in the “global definition of ARDS”.42 This new definition still includes the Berlin Consensus corrective formula for altitude,43 and, although it can use both SpO2 and FiO2 for calculation, the equation remains inaccurate, particularly for severity stratification.6,8 A recent multicenter study in Latin America found that, in patients with ARDS in high-altitude ICUs, the severity of inflammation is more strongly associated with mortality than respiratory failure. These findings underscore the importance of considering inflammatory parameters when evaluating prognosis in ARDS patients, especially in high-altitude settings.44 This study is significant because it is a pioneering initiative among high-altitude physicians to identify critical clinical parameters that predict mortality or survival in ARDS patients in high-altitude ICU settings. Research such as this study opens a new avenue of knowledge and may be useful for updating the diagnostic criteria and treatment of ARDS.

Recently, articles and research on elastic static power and its correlation with ARDS severity in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation have also been published. However, although elastic static power emerges as a possible marker related to ARDS severity, prospective studies are needed to validate these findings.45,46

The major limitation of the present consensus is the limited number of references available in the medical literature on critical care medicine at high altitudes. Moreover, the available studies are heterogeneous in their use of terms and physiological reference parameters. Nevertheless, these limitations are strengths because this international consensus, although primarily focused on Andean populations, is a significant step toward standardizing critical patient care in high-altitude environments and paves the way for future research to enhance care practices in our units.

ConclusionsThe High-Altitude Medicine Committee of the Pan-American and Iberian Federation of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care has reached a consensus that represents a fundamental advance in the standardization of key concepts for treating critical patients in high-altitude settings. The consensus aims to serve as a reference framework for clinical practice, teaching, and research in these contexts. Clearly defining critical care medicine terms at high altitudes will unify the parameters to be used in future research and publications studying critical patients living above 1,500 masl. Setting goals for the critically ill patients requiring invasive or noninvasive oxygen therapy at high altitudes will limit the possibility of hyperoxia and prevent injury due to oxygen toxicity. In the 5th century B.C., Hippocrates commented on healing, saying that we should not pay much attention to beautiful theories, but rather to experience combined with reason.47 In the absence of recommendations and evidence on managing critically ill patients at high altitudes, this Hippocratic principle guided the development of the consensus, particularly regarding acute respiratory failure.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll the authors participated in the project, contributed to drafting the text, and approved the final version.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo AI was used in the preparation of the manuscript.

Financial supportThis work has not received any funding.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.