In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of patients affected by oncohematologic diseases in developed countries due to the improved survival rates and quality of life. This increase has generated a greater need for care in intensive care units (ICU), mainly due to complications related to immunosuppression, treatment toxicity or complications derived from cancer itself. Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment, but it can cause serious side effects such as cytokine release syndrome and hemophagocytic syndrome, which often require ICU admission. This review seeks to expand knowledge and management strategies for these complications in the ICU.

En los últimos años se ha producido un incremento de pacientes afectos por enfermedades oncohematológicas en los países desarrollados, secundario a la mejora en las tasas de supervivencia y la calidad de vida. Este aumento ha generado una mayor necesidad de asistencia de los mismos en los servicios de medicina intensiva (SMI), principalmente debido a complicaciones relacionadas con inmunosupresión, la toxicidad del tratamiento o complicaciones derivadas del propio cáncer. La inmunoterapia ha transformado el tratamiento del cáncer, pero puede causar efectos secundarios graves como el síndrome de liberación de citocinas y el síndrome hemofagocítico, los cuales a menudo requieren ingreso en los SMI. Esta revisión busca expandir el conocimiento y las estrategias de manejo de estas complicaciones en los SMI.

Traditionally, antineoplastic treatment has relied on the cytotoxic capacity of chemo- and radiotherapy to destroy tumor cells. However, in recent years, the development of immunotherapy has brought about a paradigm shift.1

Immunotherapy involves boosting the patient's immune system to destroy the cancer cells. This treatment modality includes:

- •

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, which are drugs that “disinhibit” the patient's T-cell, making it easier for them to recognize and destroy tumor cells.

- •

T-cell transfer therapy involves extracting immune cells that are active against the patient’s cancer. After selection or genetic modification to specifically recognize tumor cells, the cells are cultured and infused back into the patient. T cells modified by the addition of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) belong to this type of treatment.

- •

Monoclonal, bispecific, or trispecific antibodies: proteins created in a laboratory from immunoglobulin variable regions that simultaneously recognize tumor and T-cell antigens. This facilitates recognition and interaction between the patient’s T-cells and tumor cells, favoring destruction of the latter.

- •

Immunomodulatory drugs, which are substances that intensify the patient's immune response against the cancer.2

However, immunotherapy is not without its problems, which are usually caused by a “hyperactive” immune system. Some of its adverse effects are life-threatening and may require ICU admission, where a multidisciplinary approach is necessary. Due to their frequency and potential severity, these effects include, particularly, the cytokine release syndrome (CRS)3 and the hemophagocytic syndrome or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) syndrome.4 These syndromes share pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical manifestations but differ in presentation and treatment.

The purpose of this review is to expand knowledge of and improve diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for these situations in the ICU.

Cytokine release syndromeCRS is a supraphysiological response that occurs following the administration of some form of immunotherapy. This therapy activates T-cells (either endogenous or infused) and/or other immune cells, especially macrophages.5 CRS is characterized by fever, which is often accompanied by arterial hypotension and/or respiratory failure. CRS is primarily associated CART-T cells and bispecific/trispecific antibodies treatment, although there have been isolated reports of CRS following other forms of immunotherapy.3

Risk factors and pathophysiologyThe development of CRS in patients treated with CAR-T cells is very frequent, with an incidence ranging from 48% to 93% in different studies and from 3% to 48% for severe CRS. The syndrome is somewhat less frequent in patients treated with bispecific antibodies (7%–72% and 17%–29%, respectively).6 The significant variation observed among different studies is due, not only to differences in the treatments administered and the patient’s clinical context, but also to the various staging systems used before 2019.7 Patients treated with CAR-T cells will often require ICU admission due to the development of CRS. Two multicenter studies, one European8 and the other American,9 have described ICU admission rates of 27% and 35%, respectively. The most frequent manifestations were arterial hypotension (70%) and respiratory failure (10%).8 ICU mortality was less than 5% in both studies.

Several risk factors for the development of CRS have been identified. Some are intrinsic to the patient's disease, such as tumor burden, tumor type, presence of basal inflammation, pre-treatment thrombocytopenia, and early cytokine elevation. Others are directly related to the administered treatment. In CAR-T therapy, the type of construct involved, the cell dose infused, the degree of expansion, and the lymphodepletion protocol all influence the risk of developing CRS.10–13

CAR-T cells are T-cells from the patient to which a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) has been added ex vivo. This receptor allows the cells to specifically recognize a tumor antigen and subsequently activate it, thanks to the presence of co-stimulatory molecules.13 Bispecific and trispecific antibodies, on the other hand, bind to an antigen of the tumor cell on one end and to CD3 on the T-cells the other end. This brings the patient's T-cells into close contact with the tumor cells, facilitating their identification and destruction.14

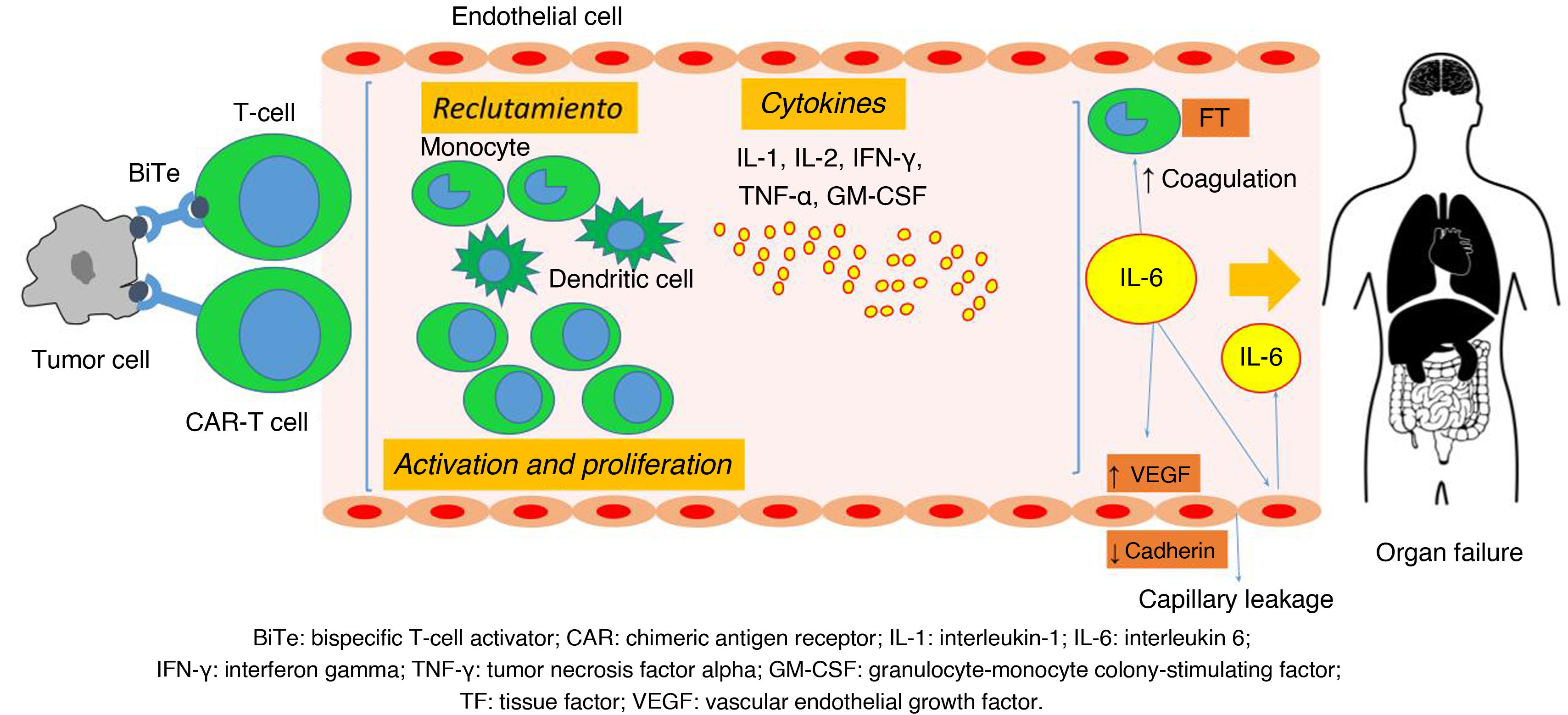

The recognition of neoplastic cells by CAR-T cells and bispecific and trispecific antibodies activates the T-cells. These activated T-cells produce effector cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN- γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This stimulates their proliferation and the recruitment of other immune system cell lines, including B-cells, NK cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. This results in the release of multiple cytokines.15–18 The destruction of the tumor cells contributes to the release of their own cytokines and the exposure of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are recognized by macrophages and amplify the response.17 Among the mediators involved in CRS, interleukins 1 and 6 (IL-1 and IL-6) play a central role in its pathophysiology,19 as demonstrated in several animal20 and clinical studies.21

This excessive immune-inflammatory response leads to endothelial and complement activation, activation of the coagulation cascade, and increased capillary permeability, which can result in multiorgan dysfunction. There is an increase in the production of endothelial growth factor, which internalizes endothelial cadherin — a structural protein that mediates cell adhesion — generating a state of capillary leakage. The activated endothelium also contributes to IL-6 production, amplifying the response15,22–26 (Fig. 1).

Physiology of cytokine release syndrome (CRS). BiTe: bispecific T-cell engager (activator); CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; TF: tissue factor; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; IL-1: interleukin-1; IL-6: interleukin-6; GM-CSF: granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Source: adapted from García Roche et al.26

CRS is characterized by the presence of fever and constitutional symptoms. It is often accompanied by arterial hypotension (67%) and/or respiratory failure (20%),27 although it can also be associated with organ dysfunction in multiple systems, including the gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, cardiac, cutaneous, and hematological systems. Neurological manifestations are considered a distinct entity known as immune effector cell-associated neurotoxic syndrome (ICANS),5 and appear within the first 14 days after CAR-T cell infusion,28 though they typically begin within the first 5–7 days.17 In contrast, the onset is earlier among patients treated with specific antibodies due to differences in their pharmacokinetics.29 The severity of symptoms can range from flu-like manifestations, with fever and constitutional symptoms, to multi-organ failure leading to the death of the patient.5

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of CRS is based on the presence of compatible clinical manifestations following the administration of certain immune therapies, as well as the exclusion of other possible causes, such as infections,30 tumor lysis syndrome,28 hematological disease progression,30 or HLH.31

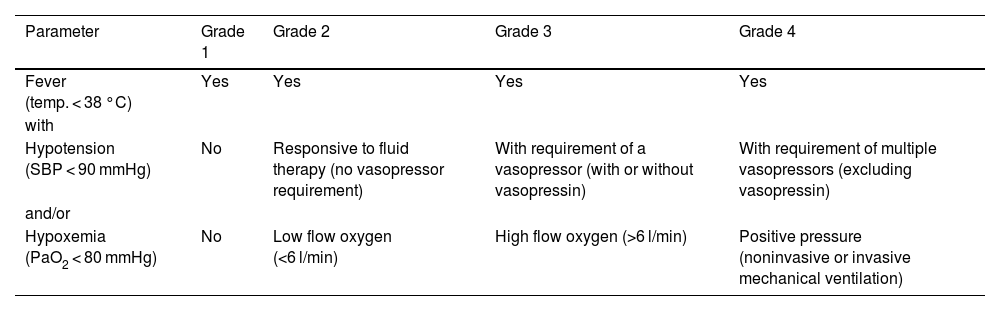

For patient management, it is important to use an internationally validated staging system. In the early years of advanced therapy development, a variety of coexisting grading systems were used,19,32–34 which made it difficult to compare the severity of CRS across different studies. Since 2019, however, unified criteria have been proposed by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT).5 According to these criteria, CRS is staged into four grades based on the presence of fever, arterial hypotension, and/or hypoxemia (Table 1).

CRS grading.

| Parameter | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever (temp. < 38 °C) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| with | ||||

| Hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg) | No | Responsive to fluid therapy (no vasopressor requirement) | With requirement of a vasopressor (with or without vasopressin) | With requirement of multiple vasopressors (excluding vasopressin) |

| and/or | ||||

| Hypoxemia (PaO2 < 80 mmHg) | No | Low flow oxygen (<6 l/min) | High flow oxygen (>6 l/min) | Positive pressure (noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation) |

CRS: cytokine release syndrome; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; PaO2: arterial oxygen pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; temp.: temperature.

Source: adapted from Lee et al.5

When using the ASTCT grading system, it is important to note that fever, arterial hypotension, and/or hypoxemia cannot be attributed to any cause other than CRS. The grade of CRS is determined by the most severe event, regardless of specific organic toxicities. For patients with CRS who have received antipyretic and/or anticytokine treatment (e.g., tocilizumab or corticosteroids), the presence of fever is no longer required for staging. In these cases, the severity of CRS is determined by arterial hypotension and/or hypoxemia.5

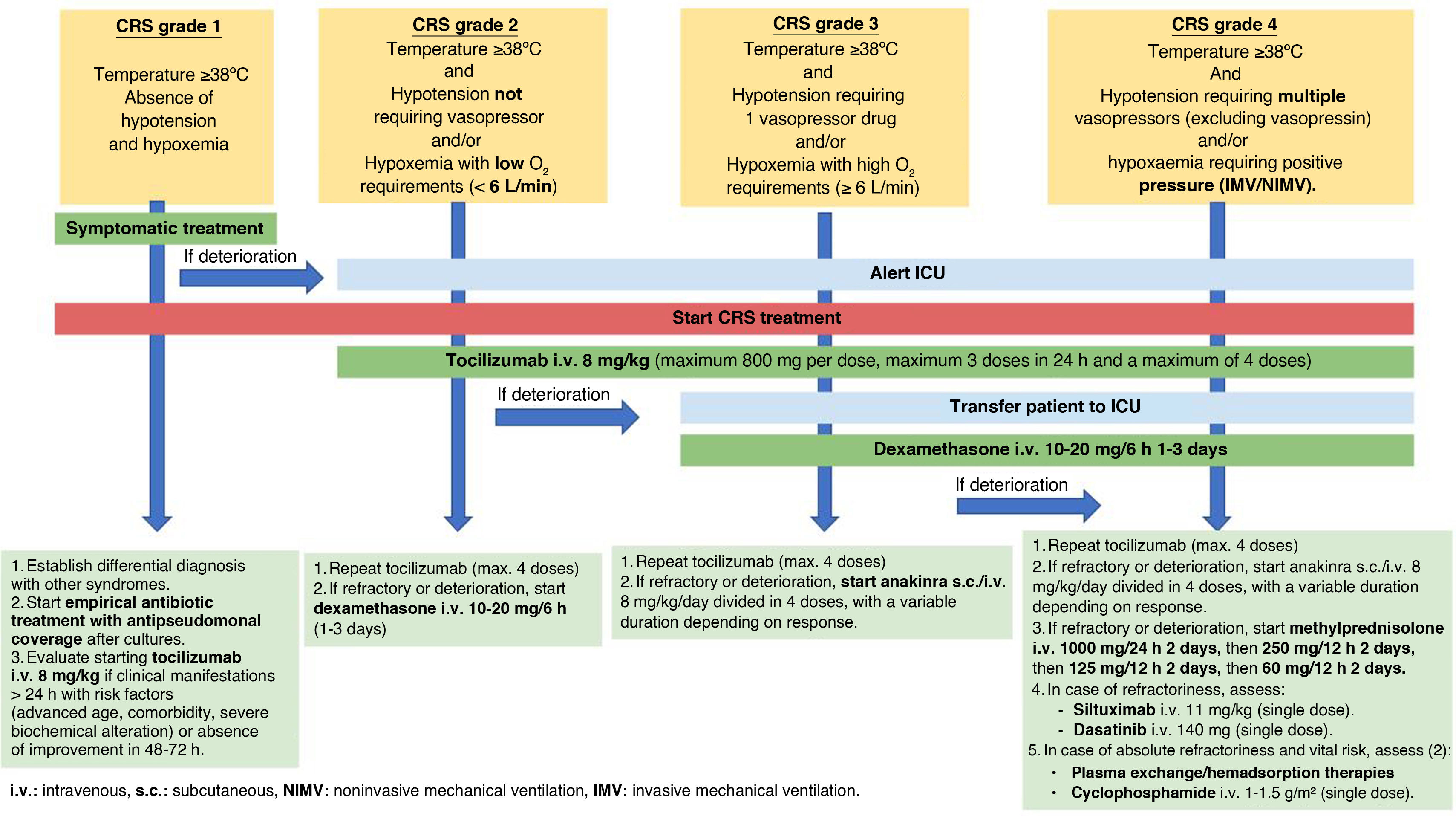

TreatmentThe treatment of CRS requires a holistic and multidisciplinary approach. Different measures are adopted depending on the stage of the disease11,13,35–37 (Fig. 2).

Grade 1 CRS: Management in the Hematology Department is advised, along with conventional supportive care, such as antipyretic medication and fluid therapy. A differential diagnosis should be made with other syndromes, especially with infectious processes, initiating empirical antibiotic therapy (with an antipseudomonal spectrum) and continuing the recommended prophylactic treatment depending on the type of immunotherapy the patient is receiving. If the patient has persistent fever for more than 24 h, is at high risk of an unfavorable outcome (due to advanced age, significant comorbidities, and/or severe biochemical alterations), or does not improve within the first 72 h, the early administration of intravenous (i.v.) tocilizumab 8 mg/kg (one-hour infusion without premedication, up to a maximum of 800 mg per dose, with a maximum of 3 doses within 24 h and a maximum of 4 doses) should be considered. Tocilizumab binds to both soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors, inhibiting signaling mediated by both.35–37 If there is a high risk of developing neurotoxicity, it is advisable to administer a single intravenous dose of 10 mg of dexamethasone when tocilizumab is employed.

Grade 2 CRS: The ICU should be notified to assess the patient initially in the Hematology ward. Then, a joint decision should be made as to whether a transfer is required. Supportive measures include administering low-flow oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation level (SpO2) > 90%, as well as fluid resuscitation to maintain a systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 90 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 60 mmHg. Due to the high risk of capillary leak syndrome and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome, caution should be exercised with fluid administration. Hemodynamic monitoring is advised to individualize resuscitation. Tocilizumab should be started, and if no clinical improvement is observed, dexamethasone i.v. 10 mg every 6−8 h can be initiated.11,35–37

Grade 3 CRS: If the patient has not been transferred to the ICU, it is advisable to do so. If the mean arterial pressure (MAP) is <65 mmHg, support with vasopressor drugs should be innitiated. Administer oxygen via high-flow therapy and/or start noninvasive mechanical ventilation to maintain a SpO2 > 90%. Initiate treatment with dexamethasone i.v. at a dose of 10 mg every 6 h if it has not been started previously. Corticosteroid treatment will be maintained for 1–3 days and/or until CRS decreases to grade 1.11,13,35–37 Maintaining tocilizumab i.v. every 8 h (up to a maximum of 4 doses) may be considered. If refractoriness occurs, increase the dose of intravenous dexamethasone to 20 mg/6 h (for 1–3 days).35 Consider starting subcutaneous (s.c.) anakinra 8 mg/kg/day divided into 4 doses, for a variable duration depending on the response.13,36 Anakinra competitively inhibits the binding of IL-1α and IL-1β to the interleukin-1 type I receptor. The addition of thiamine i.v. 500 mg every 8 h (first 72 h) followed by 500 mg every 24 h (until resolution of CRS),37 may also be considered.

CRS grade 4: Patient management should be performed in the ICU in all cases. It is advisable to intensify vasoactive and respiratory support, as well as increase the dexamethasone dose to 20 mg intravenously every 6 h for 3 days. If CRS improves, gradually withdraw the medication over 3–7 days. If refractoriness occurs, start a regimen of methylprednisolone i.v. at 1000 mg/24 h for 2 days, followed by 250 mg/12 h for 2 days, then 125 mg/12 h for 2 days, and finally 60 mg/12 h for 2 days (with subsequent suspension).13,36

Some patients may present with severe CRS (grades 3–4) that does not respond to the recommended treatment, even with the optimal use of tocilizumab and corticosteroids.38 In these cases, the available scientific evidence is limited.

In this regard, the literature provides positive data on various interventions, though publication bias cannot be ruled out. Immunomodulatory drugs, such as anakinra,39 siltuximab,40 ruxolitinib,41 emapalumab,42 or etanercept43 have been tested, with good results. Anakinra is the drug for which the most experience exists, and it is advisable to administer it via the intravenous route (instead of s.c.) to patients with edema. Another possibility is the use of treatments that block CAR-T in a reversible (dasatinib)44 or irreversible (cyclophosphamide)45 manner. Favorable responses to extracorporeal therapies such as hemofiltration,46 hemadsorption,47 or plasma exchange48 have also been described.

It is also essential to rule out other conditions that could be either an alternative diagnosis or a contributing factor, such as infection/sepsis, immunotherapy-associated HLH, or progression of the underlying oncological disease.

While waiting for the patient to respond to the initiated treatments, supportive management of multiorgan dysfunction should be established. In the absence of specific recommendations, it seems logical that the guidelines for monitoring and treating refractory septic shock could be applied to these patients,49 given the underlying pathophysiology.

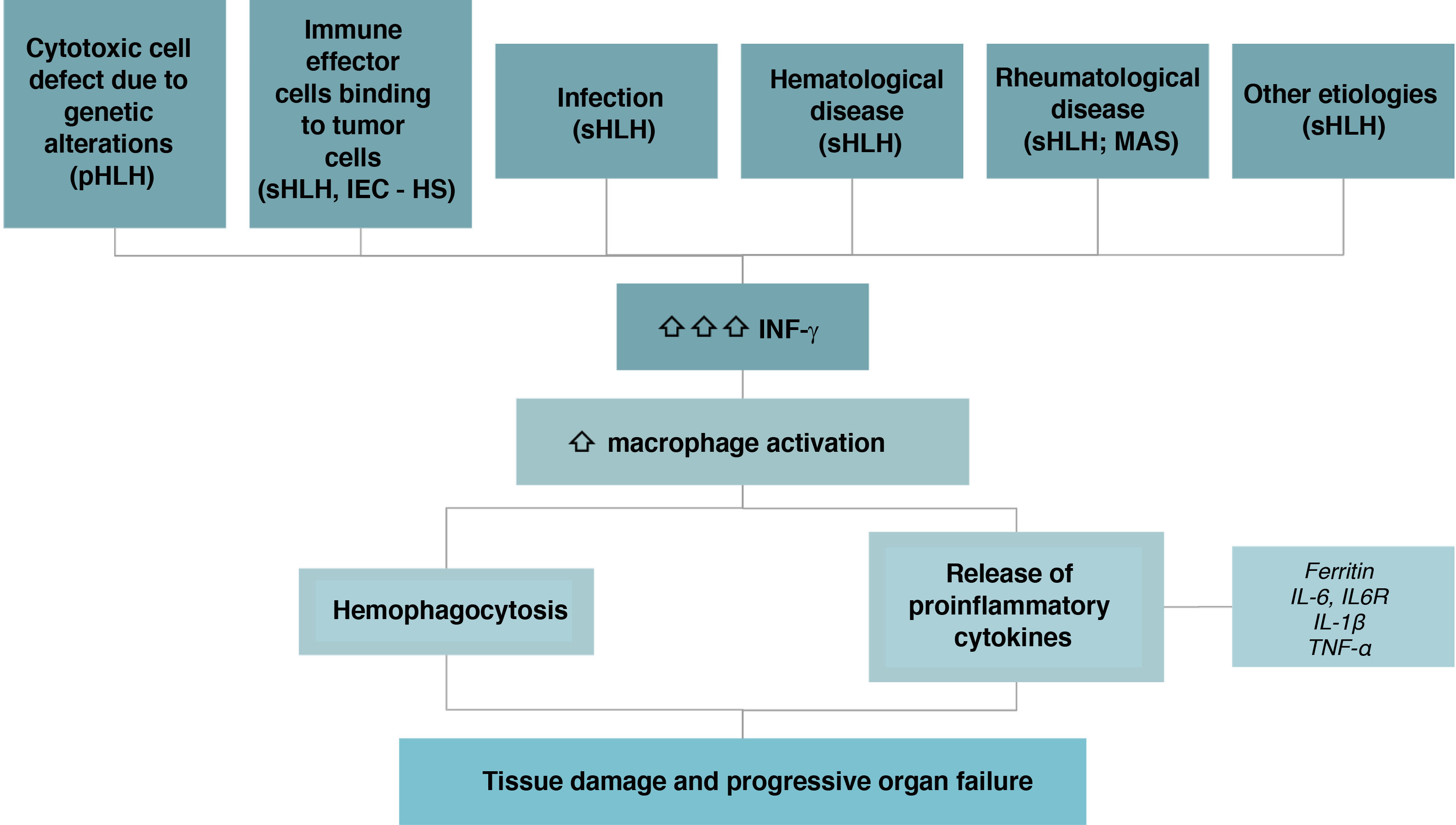

Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with immune effector cell therapyHemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome, also called HLH, is characterized by an excessive activation of T-cells and macrophages, which leads to systemic hyperinflammation and hemophagocytosis. There are two types:

- •

Primary (pHLH): Associated with pediatric patients. It is an autosomal recessive genetic disease caused by variants in the genes that regulate the function of cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells, or by defects in inflammasome regulation. Such alterations result in negative down-regulation of the inflammatory response.

- •

Secondary (sHLH): This term refers to the clinical syndrome that occurs in the absence of an identifiable hereditary defect in cytotoxicity. It is the leading form in adults and has been categorized according to the underlying triggers:

- o

Infections: This is the most frequent presentation, and can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, or fungi.

- o

Malignant neoplasms: Mainly non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and to a lesser extent, acute leukemias and Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- o

Rheumatologic diseases: This presentation is primarily associated with Still's disease, lupus erythematosus, and vasculitis. In these cases, it is usually referred to as macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

- o

Related to treatment with immune effector cell therapies (IEC-HS, immune effector cell-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome): a hyperinflammatory syndrome secondary to CAR-T cell therapy or bispecific/trispecific T cell-activating drugs. This is the condition we refer to in the present manuscript.

- o

Others: Metabolic disorders, iatrogenic conditions (e.g., after surgery or vaccine administration), and post-traumatic conditions.4,31,50

- o

IEC-HS is caused by a defect in the mechanisms that inhibit inflammation. This defect triggers the uncontrolled release of IFN-γ, which activates macrophages with hemophagocytosis and the release of inflammatory cytokines (ferritin, TNF-α, and IL-6, among others). This results in an exaggerated inflammatory response that contributes to tissue damage and multiorgan failure (Fig. 3).

Since our focus is on HLH secondary to immune effector cell therapies treatment, we will henceforth refer to the syndrome as IEC-HS.

In IEC-HS, the immune effector cells are activated upon the recognition of antigens presented by tumor cells. This leads to tumor cell lysis and expansion of the immune effector cell population, followed by proliferation and sustained cytokine release. Risk factors for developing HS-ICD include the hematological disease itself (tumor burden, proliferation dynamics, or immune resistance mechanisms), treatment (target antigen, co-stimulators, or cell dose), and patient-specific factors (baseline inflammation, immunosuppression, cytopenias, or genetic predisposition).4,31,50 IEC-HS and CRS thus share pathophysiological mechanisms. In fact, IEC-HS is usually preceded by CRS, though not always. It is difficult to determine when the transition occurs, since the two conditions can also share clinical manifestations such as fever, arterial hypotension, and hypoxemia. IEC-HS has characteristic alterations, however.50

SymptomatologyThe typical clinical presentation of IEC-HS includes fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. With regard to the laboratory test findings, cytopenias and elevated transaminase levels are common. More specific alterations include elevated ferritin, triglycerides, and soluble IL-2 receptor, decreased fibrinogen, and the presence of hemophagocytosis in various organs, particularly the bone marrow and liver.50

Patients with IEC-HS usually require ICU admission due to acute respiratory failure and/or distributive shock. Other frequent causes of admission include acute renal failure, encephalopathy, acute liver failure, hemorrhagic complications, and multiorgan failure.4,31,50–53

The ICU mortality rate among patients presenting with HLH generally varies between 40%–70%.51–53 Factors associated with mortality include patient age, the presence of hemophagocytic cells in the bone marrow aspirate, multiorgan failure on admission, and an SOFA score increase during ICU stay.50

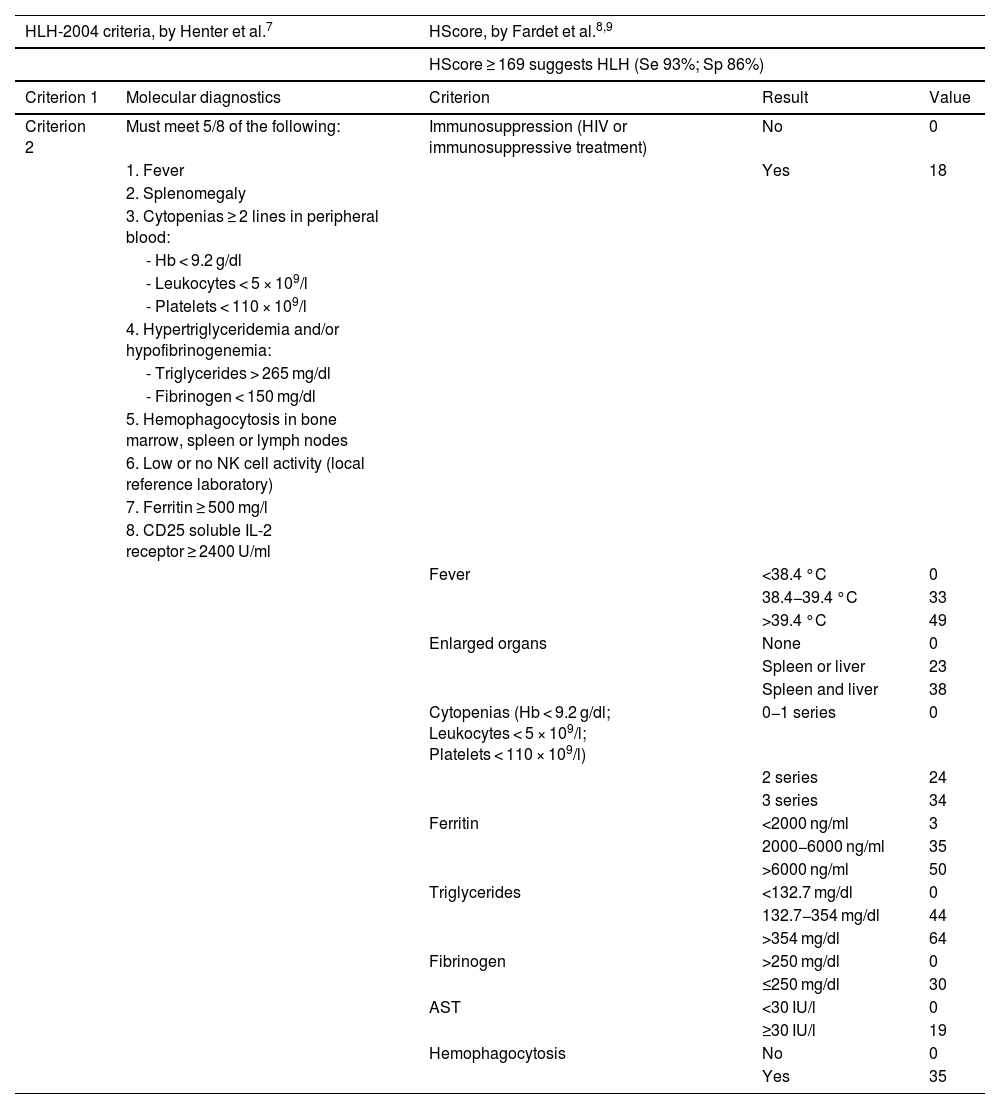

DiagnosisIn order to diagnose HLH, it is essential to suspect the disorder. Due to its high mortality rate, an early diagnosis is vital. Although there are no universally accepted criteria for sHLH diagnosis, scales such as the HLH-2004 and the H-Score are widely used, without validation in critically ill patients54–56 (Table 2).

HLH-2004 and HScore criteria for the diagnosis of sHLH.

| HLH-2004 criteria, by Henter et al.7 | HScore, by Fardet et al.8,9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HScore ≥ 169 suggests HLH (Se 93%; Sp 86%) | ||||

| Criterion 1 | Molecular diagnostics | Criterion | Result | Value |

| Criterion 2 | Must meet 5/8 of the following: | Immunosuppression (HIV or immunosuppressive treatment) | No | 0 |

| 1. Fever | Yes | 18 | ||

| 2. Splenomegaly | ||||

| 3. Cytopenias ≥ 2 lines in peripheral blood: | ||||

| - Hb < 9.2 g/dl | ||||

| - Leukocytes < 5 × 109/l | ||||

| - Platelets < 110 × 109/l | ||||

| 4. Hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia: | ||||

| - Triglycerides > 265 mg/dl | ||||

| - Fibrinogen < 150 mg/dl | ||||

| 5. Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen or lymph nodes | ||||

| 6. Low or no NK cell activity (local reference laboratory) | ||||

| 7. Ferritin ≥ 500 mg/l | ||||

| 8. CD25 soluble IL-2 receptor ≥ 2400 U/ml | ||||

| Fever | <38.4 °C | 0 | ||

| 38.4−39.4 °C | 33 | |||

| >39.4 °C | 49 | |||

| Enlarged organs | None | 0 | ||

| Spleen or liver | 23 | |||

| Spleen and liver | 38 | |||

| Cytopenias (Hb < 9.2 g/dl; Leukocytes < 5 × 109/l; Platelets < 110 × 109/l) | 0−1 series | 0 | ||

| 2 series | 24 | |||

| 3 series | 34 | |||

| Ferritin | <2000 ng/ml | 3 | ||

| 2000−6000 ng/ml | 35 | |||

| >6000 ng/ml | 50 | |||

| Triglycerides | <132.7 mg/dl | 0 | ||

| 132.7−354 mg/dl | 44 | |||

| >354 mg/dl | 64 | |||

| Fibrinogen | >250 mg/dl | 0 | ||

| ≤250 mg/dl | 30 | |||

| AST | <30 IU/l | 0 | ||

| ≥30 IU/l | 19 | |||

| Hemophagocytosis | No | 0 | ||

| Yes | 35 | |||

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; Hb: hemoglobin.

Source: adapted from Henter et al.55

In 2018, Neepalu et al.34 published new criteria for IEC-HS diagnosis, which were expanded in 2023 by Hines et al.31 to include the diagnosis of HLH. To diagnose IEC-HS, it is essential to have an elevated serum ferritin level (>2 times the upper limit of normal or the baseline value at infusion and/or rapid increase) in conjunction with typical clinical manifestations: liver toxicity grade ≥3 (increased bilirubin, AST or ALT > 5 times the upper limit of normal), cytopenias (new onset, worsening of existing cytopenias, or refractory cytopenias) with at least one line showing grade 4 according to the CTCAE,57 hypofibrinogenemia (<150 mg/dl) and tissue hemophagocytosis. Other clinical manifestations may include elevated LDH, coagulation disorders, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, new-onset splenomegaly, fever, neurotoxicity, pulmonary manifestations (such as hypoxia, lung infiltrates, and pulmonary edema), renal failure of new onset, and hypertriglyceridemia (fasting concentration > 265 mg/dl or ≥3 mmol/l).

Depending on the symptomatology, IEC-HS can be classified into 5 grades31:

- •

Grade 1: Asymptomatic or mild symptoms. Observation is required. No treatment is needed.

- •

Grade 2: Mild to moderate symptoms. Treatment is required.

- •

Grade 3: Severe symptoms, such as arterial hypotension, respiratory failure, renal failure, or bleeding. Urgent treatment is required.

- •

Grade 4: Life-threatening symptoms (more dysfunction than in grade 3). Immediate intervention is required.

- •

Grade 5: Death.

Unlike CRS, the grading system does not directly influence the type of treatment established, but only the speed of the intervention required.

An early diagnosis is vital. Other possible etiologies, such as progression of the underlying hematological malignancy, the appearance of a new neoplastic process, and/or the existence of an infectious disorder, must be ruled out. If there is a suspicion of IEC-HS, the patient should be closely monitored, with daily measurements of ferritin, LDH, fibrinogen, transaminases, bilirubin, and creatinine. If hypofibrinogenemia is present, values should be maintained above 150 mg/dl,58 and/or fibrinogen functionality should be assessed using viscoelastic testing.

TreatmentPatient management consists of immunomodulatory (etiological) treatment and multi-organ supportive therapy.

Regarding immunomodulatory treatment specifically, it should be noted that IEC-HS is typically accompanied by CRS or ICANS symptoms, meaning the patient has likely already received tocilizumab (8 mg/kg i.v.) and corticosteroids.

In cases of suspected progression of CRS to IEC-HS, anakinra is suggested as the first-line treatment, although the existing evidence is scarce. There is no consensus on the appropriate dosage. High doses of anakinra (>200 mg/day i.v.) in the form of 100−200 mg every 6–12 h i.v. could be used safely in severe cases, and may result in a superior response compared to low doses (100−200 mg/day s.c.).60 This treatment can be combined with corticosteroids (dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 h i.v.).31,59 In some case series, anakinra treatment lasted up to 7 days.61

Some authors prefer not to extend the anakinra treatment. If no improvement is observed within 48 h (clinically and biochemically, with triglyceride and IL-2 determinations), they suggest switching to another strategy, such as ruxolitinib. Ruxolitinib is a selective inhibitor of Janus kinases (JAKs) JAK1 and JAK2, which mediate the signaling of various cytokines and growth factors that are important for hematopoiesis and immune function. Ruxolitinib suppresses the macrophage overstimulation that characterizes IEC-HS in murine models.62,63 The suggested dose is 0.3 mg/kg/day orally, distributed in two doses (10 mg/kg/12 h, for an adult weighing 70 kg),31 although dosage adjustment is necessary when co-administered with CYP450 inhibitors.

Other therapeutic options that may be considered include:

- •

Etoposide: A topoisomerase-II inhibitor that effectively induces DNA damage and subsequent apoptosis in hyperactivated immune cells. It has been widely used to treat HLH, usually at doses of 75−100 mg/m2/4–7 days.58,64

- •

Intrathecal cytarabine (100 mg) with or without intrathecal hydrocortisone (50−100 mg) if there is associated ICANS.58

- •

Emapalumab: This is a human monoclonal antibody directed against IFN-γ. It is the first FDA-approved therapy for pHLH (pending approval in Europe).65

- •

A recent multicenter clinical trial (phase 2, non-randomized) has demonstrated the benefit of combining ruxolitinib (0.3 mg/kg/day for 5 days) with doxorubicin (25 mg/m2, on day 1), etoposide (100 mg/m2, on day 1) and methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg/day, on days 1 and 5 of treatment) as IEC-HS rescue therapy.66

Infections and sepsis are common among patients undergoing immunotherapy, affecting 10%–40% of all cases, especially during the first few days after the infusion.8,67,68

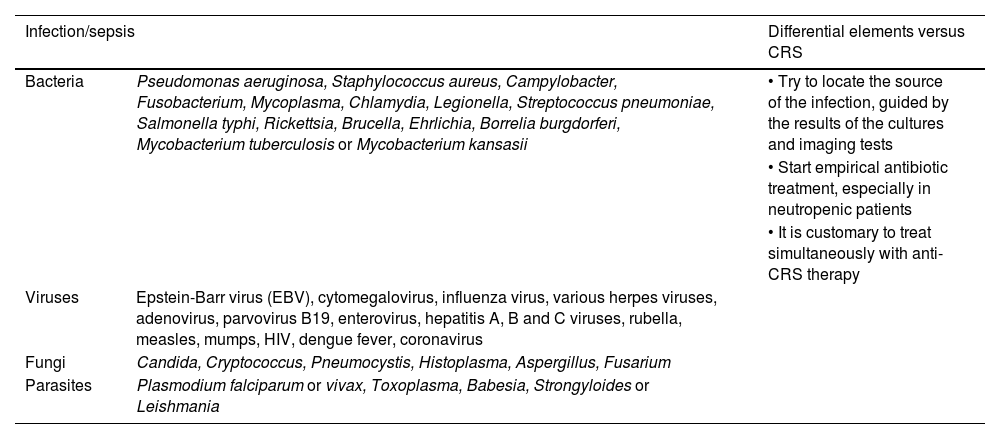

The differential diagnosis between CRS and sepsis is difficult, because they share signs and symptoms (similar pathophysiology), temporality, and risk factors.69 Therefore, it is essential to take microbiological samples, perform imaging studies adjusted to the patient's clinical condition, and initiate empirical antibiotic therapy with an antipseudomonal spectrum early on. When studying possible infectious causes, the epidemiological context of the patient must be considered, since we frequently treat patients with active hematological neoplasms, neutropenia, and multidrug-resistant germ colonization (Table 3).

Main infectious etiologies in the oncohematological population.

| Infection/sepsis | Differential elements versus CRS | |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter, Fusobacterium, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella typhi, Rickettsia, Brucella, Ehrlichia, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium kansasii | • Try to locate the source of the infection, guided by the results of the cultures and imaging tests |

| • Start empirical antibiotic treatment, especially in neutropenic patients | ||

| • It is customary to treat simultaneously with anti-CRS therapy | ||

| Viruses | Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus, influenza virus, various herpes viruses, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, enterovirus, hepatitis A, B and C viruses, rubella, measles, mumps, HIV, dengue fever, coronavirus | |

| Fungi | Candida, Cryptococcus, Pneumocystis, Histoplasma, Aspergillus, Fusarium | |

| Parasites | Plasmodium falciparum or vivax, Toxoplasma, Babesia, Strongyloides or Leishmania | |

CRS: cytokine release syndrome; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Source: own elaboration.

From a clinical point of view, distinguishing between sepsis and CRS is practically impossible, since they share common characteristics. However, some differences may help establish the differential diagnosis. Firstly, CRS tends to develop slightly earlier,8,67,70 and there are profiles of certain cytokine markers or endothelial dysfunction biomarkers that could help distinguish between these entities in the future, thus allowing for a more targeted treatment.70–74

Future prospectsImmunotherapy has completely transformed the landscape of oncospecific treatment, and it is poised to become a mainstay of care for a wide range of neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases in the near future. Combined with a better understanding of the pathophysiology, new strategies for prophylactic and curative approaches of the associated toxicities are being evaluated. These strategies involve identifying predictive toxicity biomarkers, which also help to establish the differential diagnosis between CRS and septic processes. Additionally, the increasing use of these therapies makes it “foreseeable” that there will be a growing incidence of CAR-T cell-induced pseudoprogression (CARTiPP), a phenomenon previously observed primarily following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. This poses a significant challenge in differentiating between patients who respond to treatment and those who do not, hindering the ability to identify patients with a higher probability of survival if they develop complications requiring life-support measures.37

The development of allogeneic CAR-T, the development of bispecific autologous CAR-T, and combinations with other drugs, appears to be the nearest future, with immense potential but also with challenges, particularly in managing associated toxicities.75 Multidisciplinary work, in which Intensive Care Medicine must be clearly involved, is essential to maximize the potential of these therapies, while also ensuring patient safety.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCoordination of the work team: Eric Mayor-Vazquez.

Drafting, revising and approving the submitted manuscript: Eric Mayor-Vázquez, Elena Cuenca-Fito, Carme Gomila, Cándido Díaz-Lagares, Pilar Marcos-Neira, Noelia Albalá, Alejandra García-Roche and Pedro Castro.

Bibliographic management: Eric Mayor-Vázquez, Elena Cuenca-Fito and Pilar Marcos-Neira.

Creation of tables and figures: Elena Cuenca-Fito, Pilar Marcos-Neira, Cándido Díaz-Lagares and Carme Gomila.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo AI has been used.

Financial supportNo funding has been received.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.