Type 1 pseudohypoaldosteronism (PHA-1) is a rare disorder characterised by aldosterone resistance in renal distal tubules. It can be classified as primary, often due to mutations in mineralocorticoid receptors, or secondary (transient), commonly associated with urinary tract malformations or infections.1

The estimated incidence is 1 in 80,000 newborns. It typically presents in the neonatal period with metabolic acidosis, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia, usually presenting in a nonspecific manner.2 Symptoms like lethargy, vomiting, and hyporexia are described. Cardiac arrest (CA) as an initial presentation is extremely rare, but may occur due to uncorrected metabolic disturbances.2,3 In the case of CA, due to PHA-1, it is critical to have a high index of suspicion to treat and address the underlying causes correctly.2

In this scientific letter, we describe the clinical presentation, acute management and later diagnosis of a 5-month-old previously healthy girl who suffered a CA in the pediatric emergency department (PED) and was later diagnosed with secondary PHA-1. Additionally, we made a literature review of similar cases previously published.

Upon arrival to the PED, the infant had mild respiratory distress with normal vital signs at triage. In the previous week, the parents described upper respiratory symptoms, reduced oral intake and decreased urine output. Her only prior medical issue was a growth delay from the age of three months. Approximately, 5 min after triage, while in the waiting room, she suffered a CA. No ECG data were available as she was not monitored at that moment.

Advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, with sinus rhythm restored after six minutes of CPR and two doses of intravenous epinephrine. During resuscitation, laboratory results revealed severe metabolic acidosis (pH 6.91, HCO₃ 6 mmol/L, lactate 31 mg/dL), hyperkalemia (10.1 mEq/L), hyponatremia (121 mEq/L), and hypocalcemia (1.18 mmol/L). Renal impairment (creatinine 2.36 mg/dL, urea 181 mg/dL), hyperuricemia (12.7 mg/dL), and hyperglycemia (>400 mg/dL) were also observed. She received bicarbonate, insulin, rasburicase, furosemide, intravenous fluids, electrolyte corrections (calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate), and urinary catheterisation. After stabilisation, she was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

In the first PICU hours, the patient required inotropic support (adrenaline up to 0.07 μg/kg/min and noradrenaline up to 0.47 μg/kg/min), intravenous fluid therapy (glucosaline 5%/0.9%, adjusting according to electrolyte levels with glucosaline 1/3 or PlasmaLyte), and multiple electrolyte replacements (monopotassium phosphate, sodium chloride, bicarbonate, magnesium sulphate, calcium chloride). Tendency to hyperkalemia and hyponatremia persisted for seven days. She also developed coagulopathy (treated with vitamin K for three days) and anemia (requiring multiple blood transfusions until the tenth day). She was extubated on day three.

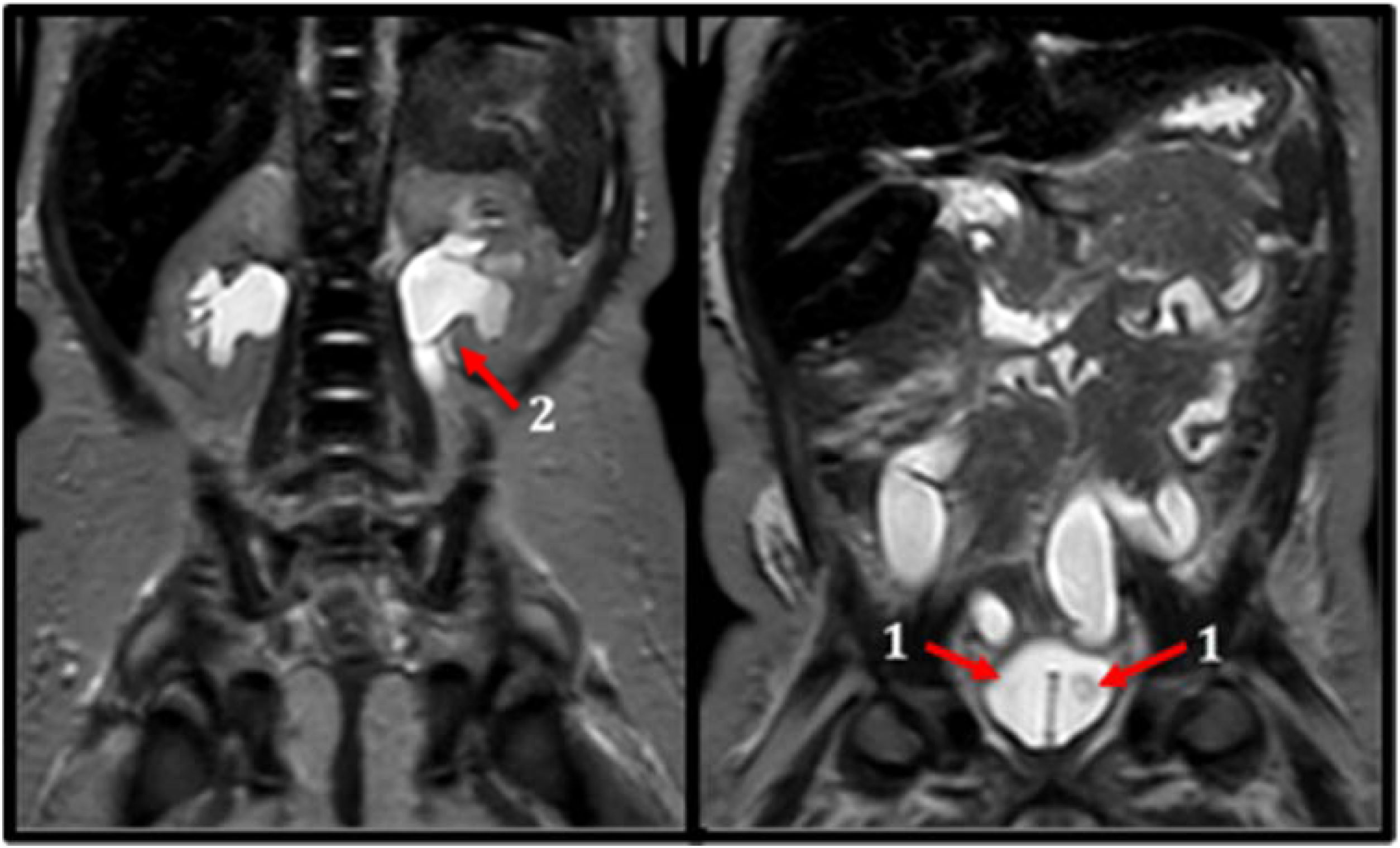

A PHA-1 was suspected. An abdominal ultrasound was done revealing bilateral intravesical ureteroceles and secondary uretero-pyelocaliceal dilatation. Diagnosis was confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), micturating cystourethrography (MCU), and renogram (Fig. 1). Later, a genetic study ruled out primary PHA-1.

Cystoscopy with bilateral ureteral orifice dilatation was performed. After this, hydroelectrolyte abnormalities progressively resolved and renal function normalised. The patient was discharged from PICU without sequelae. Follow-up showed appropriate neurodevelopment with a normal brain MRI.

This case highlights an uncommon cause of CA in infants. As it is known, reversible causes of CA must be promptly identified and corrected in the PED (hypoxia, hypothermia, hypovolemia, hypo/hyperkalemia, tension pneumothorax, thrombosis, toxins and cardiac tamponade).4 Hyperkalemia and hyponatremia led us to suspect a probable PHA-1. While congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is often considered in case of hyperkalemia, PHA-1 may not be considered.3,5

The pathophysiology of PHA-1 involves resistance to aldosterone in the renal tubules, leading to impaired sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion, resulting in hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis.1 Clinical presentation is nonspecific including symptoms such as lethargy, vomiting, weight loss, and feeding refusal.6,7 Electrocardiographic changes (e.g., peaked T waves, arrhythmias, ventricular fibrillation) can provide diagnostic clues, especially associated with electrolytic imbalances. Unfortunately, pre-arrest ECG was unavailable in our case.5

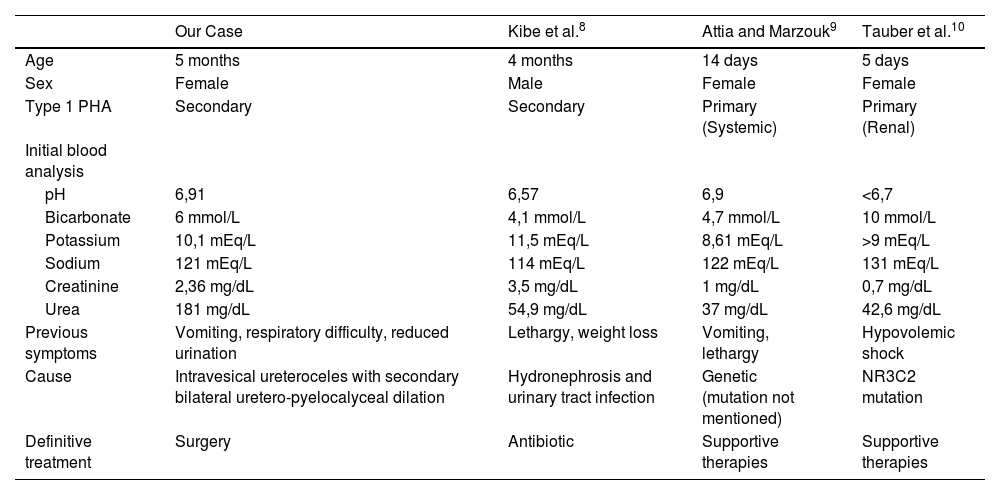

Complementary tests carried out during CPR may allow us to suspect underlying and treatable causes. After reviewing the literature, we find very few cases describing CA as the initial presentation of PHA-1. Only one case was reported as the initial presentation of secondary PHA-1 (Table 1).7

Cases of PHA with CA as first clinical presentation, literature review.

| Our Case | Kibe et al.8 | Attia and Marzouk9 | Tauber et al.10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 5 months | 4 months | 14 days | 5 days |

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Type 1 PHA | Secondary | Secondary | Primary (Systemic) | Primary (Renal) |

| Initial blood analysis | ||||

| pH | 6,91 | 6,57 | 6,9 | <6,7 |

| Bicarbonate | 6 mmol/L | 4,1 mmol/L | 4,7 mmol/L | 10 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 10,1 mEq/L | 11,5 mEq/L | 8,61 mEq/L | >9 mEq/L |

| Sodium | 121 mEq/L | 114 mEq/L | 122 mEq/L | 131 mEq/L |

| Creatinine | 2,36 mg/dL | 3,5 mg/dL | 1 mg/dL | 0,7 mg/dL |

| Urea | 181 mg/dL | 54,9 mg/dL | 37 mg/dL | 42,6 mg/dL |

| Previous symptoms | Vomiting, respiratory difficulty, reduced urination | Lethargy, weight loss | Vomiting, lethargy | Hypovolemic shock |

| Cause | Intravesical ureteroceles with secondary bilateral uretero-pyelocalyceal dilation | Hydronephrosis and urinary tract infection | Genetic (mutation not mentioned) | NR3C2 mutation |

| Definitive treatment | Surgery | Antibiotic | Supportive therapies | Supportive therapies |

Initial stabilisation includes cardiac membrane protection with calcium gluconate, volume resuscitation and electrolyte correction under continuous cardiac monitoring. For this, it is usually necessary to transfer to the PICU.2,3 In the first hours, the differential diagnosis should include measurement of serum electrolytes and acid-base balance, and later, plasma renin activity, aldosterone levels, and cortisol. In PHA-1, plasma renin and aldosterone levels are markedly elevated, while cortisol levels are normal, distinguishing it from CAH.5 Added to this, imaging tests such as abdominal ultrasound or MRI could be useful to detect surgically treatable causes (Fig. 1).

Differentiating between primary (genetic) and secondary (reversible) PHA-1 is essential for prognosis and management. While primary PHA-1 requires long-term monitoring and supplementation (high-sodium and low-potassium diets, hydration, etc.), secondary forms may be fully reversible by correcting the underlying cause (e.g., antibiotics, surgery).1 In our patient, surgical correction, consisting of bilateral ureteral orifice dilation, resolved the condition.

In conclusion, here we present a rare cause of CA in an infant. This case illustrates the importance of considering PHA-1 as a possible cause. The presence of unexplained electrolyte disturbances (hyperkaliemia and hyponatremia) may help to its suspicion. Prompt recognition and correction of these imbalances is critical. Definitive diagnosis requires studying the renin-angiotensin axis, along with complementary imaging and genetic tests. In secondary forms, treating the underlying cause can lead to complete resolution of the PHA-1.

ORCID IDAlberto García-Salido: 0000-0002-8038-7430

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll the authors participated in patient care. MCC and SBN collected the clinical data, wrote the first draft and reviewed the paper. AGS collaborated in the design, writing and review. All authors reviewed the document and provided suggestions for the final version.

Ethics approvalApproved by the hospital ethics committee. The work was completed in compliance with the ethical standards.

FundingNot funding.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.