Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction is a relatively common organ dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock.1,2 In addition, pre-existing cardiac diseases are also common especially in the elderly with sepsis. Sepsis and septic shock are characterized by vasoplegia and subsequent hyperdynamic cardiac state, with interventions mostly guided towards restoring vascular tone. While the occurrence of cardiac dysfunction, particularly cardiogenic shock may require a deviation from this standardized approach, very little is known about cardiogenic shock complicating sepsis. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the prevalence and impact on in-hospital mortality of cardiogenic shock complicating sepsis and septic shock.

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which is a large administrative database of hospital inpatient discharges in the United States (US) produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It consists of a stratified sample of approximately 20% of all discharges in US hospitals. The sampling method of the NIS allows the application of weighting variables that enables the calculation of national estimates, which was validated against other US hospital registries.3 Inclusion criteria were: 1) age ≥ 18 years and 2) admitted to the hospital for the primary diagnosis of sepsis and septic shock during January 2017 to December 2019. We identified sepsis with the primary diagnosis of any of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes specified in the denominator for the CMS SEP-1 measure; A02.1, A22.7, A26.7, A32.7, A40.0, A40.1, A40.3, A40.8, A40.9, A41.01, A41.02, A41.1, A41.02, A41.1, A41.2, A41.3, A41.4, A41.50, A41.51, A41.52, A41.53, A41.59, A41.81, A41.89, A41.9, A42.7, A54.86, B37.7, R65.20, and R65.21.4 Septic shock was defined as the primary diagnosis of “septic shock”, the primary diagnosis of “sepsis” and the secondary diagnosis of “septic shock”, or the primary diagnosis of “sepsis” and the procedure codes of “vasopressor support”.5 Vasopressor support was identified using the following procedure codes; 3E043XZ or 3E033XZ. Cardiogenic shock was defined using the previously validated diagnosis code; R57.0.6 We described the prevalence of cardiogenic shock among patients with sepsis and septic shock. We also performed the logistic regression analysis to investigate the association between cardiogenic shock complicating sepsis and septic shock and in-hospital mortality adjusting for age, sex, race, Elixhauser comorbidity index, primary payers, hospital characteristics, and the median incomes of the hospital area. Age, the median incomes of the hospital area, primary payers, race, female or not, died or not, and whether the admission was on weekend or not were missing in 0.0016%, 1.9%, 0.11%, 2.3%, 0.0047%, and 0.0004% respectively. We performed multiple imputation with chained equation and 20 imputations for these missing values. All analyses were performed after weighting the unweighted observations to create the national estimates using Stata MP version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Queen’s Medical Center (Reference number: RA-2022-032).

A total of 1,003,874 hospitalizations with the primary diagnosis of sepsis and septic shock were identified (septic shock 193,709). National estimate of hospitalizations for sepsis during the study period were 50,193,369 hospitalizations (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4,948,510–5,090,229), of which septic shock accounted for 968,545 hospitalizations (95%CI: 954,303–982,787). While only 0.3% (12,755/4,050,824) had a cardiogenic shock in patients with sepsis, 4.6% (44,980/968,545) had documented cardiogenic shock in patients with septic shock. The detailed characteristics were shown in Table 1. The presence of cardiogenic shock was associated with significantly higher odds of in-hospital mortality both in patients with sepsis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 10.07, 95%CI: 9.19–11.04, p<0.001) and those with septic shock (aOR: 2.20, 95% CI: 2.10–2.30, p<0.001), as shown in Table 2.

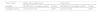

Patient’s characteristics.

| Total number of hospitalizations | Sepsis (n=1,003,874) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National estimate (n=5,019,369) | ||||

| (95%CI: 4,948,510–5,090,229) | ||||

| Type of sepsis | Sepsis without septic shock (n=810,165) | Septic shock (n=193,709) | ||

| National estimate (n=4,050,824) | National estimate (n=968, 545) | |||

| (95%CI: 3,990,419–4,111,229) | (95%CI: 954,303–982,787) | |||

| Characteristics | CS (−) (n=807,614) | CS (+) (n=2551) | CS (−) (n=184,713) | CS (+) (n=8996) |

| National estimate | National estimate | National estimate | National estimate | |

| (n=4,038,069) | (n=12,755) | (n=923,565) | (n=44,980) | |

| (95%CI: 3,977,833–4,098,305) | (95%CI: 12,193–13,317) | (95%CI: 910,017–937,113) | (95%CI: 43,581–46,379) | |

| Age, year (mean [SD]) | 64.5 (18.0) | 69.3 (14.7) | 67.5 (15.2) | 68.3 (14.6) |

| Female (%) | 50.6% | 43.7% | 49.7% | 43.1% |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (mean [SD]) | 4.2 (2.2) | 6.6 (2.1) | 5.4 (2.2) | 6.6 (2.1) |

| Bed size of hospital (%) | ||||

| 1. Small | 1. 22.8% | 1. 18.2% | 1. 19.2% | 1. 15.2% |

| 2. Medium | 2. 31.2% | 2. 32.8% | 2. 30.8% | 2. 27.5% |

| 3. Large | 3. 46.1% | 3. 49.0% | 3. 49.9% | 3. 57.2% |

| Location/teaching status of hospital (%) | ||||

| 1. Rural | 1. 10.5% | 1. 6.3% | 1. 7.8% | 1. 4.6% |

| 2. Urban nonteaching | 2. 24.5% | 2. 21.8% | 2. 22.4% | 2. 18.1% |

| 3. Urban teaching | 3. 65.0% | 3. 71.9% | 3. 69.8% | 3. 77.4% |

| Region of hospital (%) | ||||

| 1. Northeast | 1. 16.0% | 1. 14.7% | 1. 16.5% | 1. 16.3% |

| 2. Midwest | 2. 20.3% | 2. 19.6% | 2. 20.2% | 2. 20.7% |

| 3. South | 3. 39.6% | 3. 41.4% | 3. 40.8% | 3. 38.9% |

| 4. West | 4. 24.1% | 4. 24.4% | 4. 22.5% | 4. 24.1% |

| Primary expected payer (%) | ||||

| 1. Medicare | 1. 60.5% | 1. 69.0% | 1. 67.3% | 1. 68.6% |

| 2. Medicaid | 2. 14.4% | 2. 11.6% | 2. 12.8% | 2. 11.9% |

| 3. Private insurance | 3. 18.3% | 3. 12.9% | 3. 14.8% | 3. 14.2% |

| 4. Self-pay | 4. 4.3% | 4. 3.4% | 4. 2.7% | 4. 2.9% |

| 5. No charge | 5. 0.4% | 5. 0.2% | 5. 0.2% | 5. 0.2% |

| 6. Other | 6. 2.1% | 6. 3.0% | 6. 2.2% | 6. 2.3% |

| Race (%) | ||||

| 1. White | 1. 69.3% | 1. 66.4% | 1. 69.5% | 1. 65.3% |

| 2. Black | 2. 13.3% | 2. 16.0% | 2. 13.5% | 2. 16.9% |

| 3. Hispanic | 3. 11.1% | 3. 11.0% | 3. 10.2% | 3. 9.9% |

| 4. Asian/Pacific Islander | 4. 3.0% | 4. 3.1% | 4. 3.1% | 4. 3.9% |

| 5. Native American | 5. 0.7% | 5. 0.7% | 5. 0.8% | 5. 0.8% |

| 6. Other | 6. 2.6% | 6. 2.8% | 6. 2.8% | 6. 3.1% |

| Year (%) | ||||

| 1. 2017 | 1. 32.2% | 1. 31.2% | 1. 32.9% | 1. 22.0% |

| 2. 2018 | 2. 33.8% | 2. 33.2% | 2. 33.4% | 2. 37.4% |

| 3. 2019 | 3. 34.0% | 3. 35.5% | 3. 33.7% | 3. 40.5% |

| Median household income national quartile for patient ZIP Code (%) | ||||

| 1. Fisrt quartile | 1. 31.1% | 1. 35.5% | 1. 32.3% | 1. 32.7% |

| 2. Second quartile | 2. 26.6% | 2. 26.3% | 2. 26.5% | 2. 26.0% |

| 3. Third quartile | 3. 23.7% | 3. 21.3% | 3. 22.9% | 3. 23.1% |

| 4. Fourth quartile | 4. 18.6% | 4. 16.8% | 4. 18.3% | 4. 18.2% |

| Weekend admission (%) | 26.6% | 26.0% | 26.9% | 27.3% |

SD: standard deviation, CS: cardiogenic shock; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ZIP, zone improvement plan.

The definition of Hospital Bed size was as below.

Northeast region: Rural: 1–49, Medium: 50–99, Large: ≥100.

Northeast region: Urban, nonteaching: Small: 1–124, Medium 125–199, Large: ≥100.

Northeast region: Urban, teaching: Small: 1–249, Medium: 250–424, Large: ≥425.

Midwest region: Rural: 1–29, Medium: 30–49, Large: ≥50.

Midwest region: Urban, nonteaching: Small: 1–74, Medium 75–174, Large: ≥175.

Midwest region: Urban, teaching: Small: 1–249, Medium: 250–374, Large: ≥375.

Southern region: Rural: 1–39, Medium: 40–74, Large: ≥75.

Southern region: Urban, nonteaching: Small: 1–99, Medium 100–199, Large: ≥200.

Southern region: Urban, teaching: Small: 1–249, Medium: 250–449, Large: ≥450.

Western region: Rural: 1–24, Medium: 25–44, Large: ≥45.

Western region: Urban, nonteaching: Small: 1–99, Medium 100–174, Large: ≥175.

Western region: Urban, teaching: Small: 1–199, Medium: 200–324, Large: ≥325.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses for in-hospital mortality.

| Type of sepsis | Sepsis without septic shock | Septic shock | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95%CI) for in-hospital mortality | P-value | OR (95%CI) for in-hospital mortality | P-value |

| Cardiogenic shock | 10.07 (9.19–11.04) | <0.001 | 2.20 (2.10–2.30) | <0.001 |

OR: odds ratio.

The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality was adjusted for age, sex, whether hospitalizations were on weekend or not, Elixhauser comorbidity index, size of hospital (small, medium or large), location/teaching status of hospital (rural, urban-nonteaching, or urban teaching), region of hospital (northeast, Midwest, south, or west), primary expected payer (medicare, medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, no charge, or others), race (white, black, Hispanic, Asian/pacific islander, native American, or others), year (2017, 2018, or 2019), and median household income national quartile for patients’ zip code (first quartile, second quartile, third quartile, or fourth quartile).

In the present study, the prevalence of cardiogenic shock among septic shock was 4.6% and the co-occurrence of cardiogenic shock in patients with sepsis and septic shock was associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality. This study is the first large study to report the prevalence and impact on in-hospital mortality of cardiogenic shock complicating sepsis and septic shock.

Our study has two important implications. Firstly, this study provided clinicians with the prevalence of cardiogenic shock among septic shock. Since septic shock is one of the most common reasons for admission to the intensive care unit, the co-occurrence of cardiogenic shock in 4.6% of septic shock requires attention. While routine assessment of cardiac function did not appear to be a high-yield in patients with sepsis without septic shock (only 0.3% had cardiogenic shock), the assessment of cardiac function in septic shock appears to be much more important given its higher prevalence. Secondly, this dramatic increase in in-hospital mortality with cardiogenic shock complicating septic shock suggests the necessity for a different approach to this specific population. While SSCGs suggest the use of inotropes in patients with myocardial dysfunction with evidence of decreased perfusion,7 there is no randomized controlled trial comparing inotropes and placebo in this specific population. Retrospective studies even reported the use of inotropic agents such as epinephrine or dobutamine was associated with significantly higher mortality.8,9 Given the lack of conclusive evidence10 but significantly higher risk of in-hospital mortality, further investigation regarding enhanced monitoring and therapeutic approaches would be urgently warranted for this specific population.

The biggest limitation of this study is that we had to rely on ICD-10 code for the diagnosis of sepsis, septic shock, and cardiogenic shock. We used the coding that were previously used or validated in other studies.4–6 However, it is still possible that there was a variation in the diagnostic criteria. Similarly, since this is a study using big data, individual-level data were not available and the hidden confounders are inevitable. Therefore, a prospective study using a protocol of routine evaluation of cardiac function to clarify our findings is warranted in the future.

In conclusion, this study described that the prevalence of cardiogenic shock complicating septic shock was 4.6% and it was associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality. This study highlights the importance of assessments of cardiac function in septic shock and further investigation for the personalized approach to this specific population.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Queen’s Medical Center’s institutional review board on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Queen’s Medical Center Reference number: RA-2022-032, Approved date: 09/16/2022, Revision approved date: 10/05/2022, Approved Title: Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Sepsis and Septic Shock: A National Inpatient Sample Analysis.

Consent for publicationNA as this is a public national database.

Competing interestsNone.

FundingK.N. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant# 20K2322).

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementRyota Sato: Methodology, Writing - original draft. Daisuke Hasegawa: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Kazuki Nishida: Formal analysis, Methodology. Siddharth Dugar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision.

NA.