Emotional factors may lead to cognitive impairment that can adversely affect the capacity of patients to reason, and thereby, limit their participation in decision taking.

PurposesTo analyze critical patient aptitude for decision taking, and to identify variables that may influence competence.

DesignAn observational descriptive study was carried out.

SettingIntensive Care Unit (ICU).

PatientsParticipants were 29 critically ill patients.

Main variablesSocial, demographic and psychological variables were analyzed. Functional capacities and psychological reactions during stay in the ICU were assessed.

ResultsThe patients are of the firm opinion that they should have the last word in the taking of decisions; they prefer bad news to be given by the physician; and feel that the presence of a psychologist would make the process easier. Failure on the part of the professional to answer their questions is perceived as the greatest stress factor. Increased depression results in lesser cognitive capacity, and for patients with impaired cognitive capacity, participation in the decision taking process constitutes a burden. The anxiety and depression variables are significantly related to decision taking capacity.

Factores emocionales pueden condicionar alteraciones cognitivas que bloqueen la habilidad del paciente para razonar, limitando su participación en la toma de decisiones.

ObjetivosEvaluar la disposición del paciente crítico para tomar decisiones e identificar qué variables pueden influir en su competencia.

DiseñoEstudio observacional descriptivo.

ÁmbitoUnidad de Cuidados Intensivos.

Pacientes29 pacientes críticos.

VariablesSe analizaron variables sociodemográficas y psicológicas. Se evaluó la capacidad funcional y la reacción psicológica durante la estancia en UCI.

ResultadosMuestran que los pacientes están totalmente de acuerdo en que la última palabra a la hora de tomar decisiones corresponde a ellos mismos, prefieren que una mala noticia sea trasmitida por el médico y dicen que la presencia del psicólogo facilitaría el proceso. Que los profesionales no respondan a sus preguntas es el factor de mayor estrés. A mayor nivel de depresión resulta una menor capacidad cognitiva, y para los pacientes con menor capacidad cognitiva, participar en la toma de decisiones supone una sobrecarga. Las variables ansiedad y depresión se relacionan significativamente con la capacidad para tomar decisiones.

As admitted by Drane,1,2 from the start the doctrine of consent has posed a series of dilemmas, since in order for a consent document not to become a mere defensive instrument, it is necessary for the patient to be competent, act autonomously, without coercion, and with sufficient cognitive capacity to be able to evaluate the illness and the benefits or consequences of treatment. Simón-Lorda et al.3 defined four situations that can cause clinicians to suspect problems in relation to patient competence:

- 1.

When the patient shows a sudden change in mental state.

- 2.

When the patient rejects a treatment that is clearly indicated, without offering a clear argument or reasons, or basing the reasons on irrational assumptions or ideas.

- 3.

When the patient freely accepts bothersome procedures without weighing the risks and benefits.

- 4.

When the patient suffers some background neurological or psychiatric disorder that may give rise to transient incapacitation.

The critically ill patient also has the right and the need to be informed. The information must be understood by the patient, since understanding is a key step in the cognitive process leading to decision taking. Furthermore, the assessment of competence is particularly relevant in such patients, because decision taking in these cases is typically done in very stressful situations.

On the other hand, healthcare professionals have the duty to establish a collaborative environment with the patients and their relatives–a setting or environment in which clinical decisions can be made jointly, with due respect for the values, objectives, and capacities of the patients.4

The ICU is a technological and human setting designed to offer integral treatment and care for critical patients, and is equipped with the specialized professionals and the complex technological means and resources needed for this purpose. The work dynamics, the patient condition, the quickness of response demanded of the professionals, and the difficulties in minimizing noise and illumination all cause the ICU to be a stressing environment.

On the other hand, critical patients are defined as those with organic, structural or functional instability, and who are in a truly or potentially life-threatening situation, or who suffer the failure or one or more vital body organs or systems. Very few critical patients are able to express their wishes; in only a few cases are there living will documents; and a previous healthcare relationship with the patient is not common.5,6 Knowing the decisions of the patient is complicated, due to the following factors:

- -

Diminished or altered consciousness.

- -

The impossibility of establishing communication (since most patients are sedated, intubated or tracheostomized).

- -

The immediateness and/or need for some clinical intervention.

- -

An emotional state altered by the disease itself or by the personal, familial, occupational and/or social situation.

- -

The existence of an unknown and stressing environment.

Adequate care of the critical patient requires team effort.7 All the healthcare professionals must think and act responsibly, and in this case a responsible attitude is to explore patient competence in depth. As pointed out by Drane,8 competence can be dependent upon the physical and mental situation, and on the environment, and as such may change over time.

Competence is directly related to mental capacity, cognitive skills, the underlying psychopathology, the information process, the relationship with the healthcare professionals, and the family and social-occupational environment of the patient. Psychology acts as a binding link giving sense to the legal and ethical dimensions involved.9 The designing of methodology for the evaluation of patient competence requires definition of the cognitive profile of the patient and of the etiology underlying cognitive impairment–establishing whether the latter is permanent, progressive or temporary. It is also necessary to prepare a report on capacity and decision taking, along with a neurological assessment, a description of the evolutive condition and of functional involvement, the prognosis, and the degree of patient dependency.10

The present study was carried out to evaluate the capacity and disposition of the critical patient for making decisions and the variables capable of influencing or affecting patient competence in this sense.

MethodParticipantsA descriptive observational study was carried out in the Department of Intensive Care Medicine (Castellón General University Hospital, Castellón, Spain), covering the period between April and September 2009, during which 548 patients were admitted to intensive care, with a mortality rate of 13.6%. Of the 473 patients who survived, only those 390 subjects with a stay of over 24h were included in the study. Of these 390 patients, 45.9% could not be interviewed because they were intubated or tracheotomized, 37.4% suffered physiopathological problems precluding communication, and 5.9% could not speak Spanish. The resulting study sample thus comprised 42 patients, of which 5 were lost due to different reasons, while 8 patients declined participation in the study. The final valid study series therefore consisted of 29 patients, representing 5.3% of the total admissions during the mentioned time period.

The great majority of the participants (96.6%) were men, and the mean patient age was 63.8 years. Regarding educational level, 3.4% had received no schooling, 72.4% had received primary education, 20.7% secondary education, and only 3.4% had higher education. In turn, as referred to marital status, 76.9% were married or had a stable couple, 15.4% were single, and 7.7% divorced. Regarding the reason for admission, 27.6% were coronary cases, 24.1% had clinical pathology, 10.3% were neurosurgical patients, 17.2% presented a septic state, and 20.7% had respiratory disease.

InstrumentsThe following instruments were used for evaluative purposes:

- -

Biological parameters.11–13 The biological parameters were selected on the basis of their capacity to alter patient competence. Specifically, we recorded carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), oxygen partial pressure (PaO2), oxygen saturation (SatO2), blood pH, sodium (Na+), blood glucose, mean blood pressure (MBP), temperature, respiratory frequency (RF), and heart rate (HR).

- -

Glasgow coma score14 and Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS)15 for assessing level of consciousness and sedation.

- -

Barthel index (BI).16 Evaluation of the capacity of the patient to independently carry out the activities of daily living.

- -

Minimental state examination test (MMSE).17 This instrument evaluates orientation, fixation memory, concentration and calculation, delayed recall, language and construction. The cutoff points have been established as ≥25=normal, while ≤24=suspected disease.

- -

Stress factors scale. This instrument is an adaptation of the hospital stressor scale developed by Richard et al.18 to evaluate the degree of discomfort associated with different stress factors related to admission and stay in the ICU. The scale comprises 40 items scored by means of a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 (1=not at all, 2=a little, 3=quite a lot, 4=much, and 5=very much), and reflects the degree of stress which the patient experiences in a given situation.

- -

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS).19 The frequency or intensity of each item is scored by means of a Likert-type scale, with scores of over 11 points reflecting anxiety or depression symptoms.

- -

Questionnaire for subjective evaluation of the information process and decision taking in the hospital setting (CITD). This is an instrument developed ad hoc and validated in a group of healthcare professionals participating on a voluntary and anonymous basis, yielding a Cronbach alpha of 0.83. The CITD was designed to collect information on the patient referred to the information process, the degree of involvement which critical patients wish to have in decision taking, the role they assign to their own relatives and/or representatives, and the degree of interest which the patients show with respect to information referred to the dying process. The CITD comprises 26 items, scored from 1 (fully disagree) to 4 (fully agree).

The interviews were carried out on a personalized basis, in a closed room in order to preserve patient privacy and confidentiality. Informed consent was previously obtained from the participants.

Data analysisThe statistical analysis was divided into two phases. First a descriptive study was made, expressing the results as the mean, standard deviation and/or percentage. Second, comparative analyses were made of the main variables as a function of the sociodemographic parameters, based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Pearson correlation test. Lastly, the patients were divided according to cognitive capacity, and the Student t-test was applied to the CITD scores.

ResultsThe descriptive analysis of the biological parameters revealed mean values above those considered normal, and outside the ranges established as reference. The Glasgow score of all the patients was 15, thus ensuring a good level of consciousness at the time of the interview. Regarding the level of sedation, all patients showed a RASS score of 0 points. The mean BI was 98.64 (σ=7.74). A little over one-half of the participants (54.5%) had a functional capacity score prior to admission to the ICU of 100.

In the descriptive analysis of the psychological variables we examined cognitive capacity based on the MMSE, which yielded a mean score of 24.11 (σ=4.50). Only 14.8% of the patients were able to answer the questionnaire. The rest (85.2%) suffered impaired cognitive capacity. An MMSE score of under 24 is consistent with moderate to severe impairment, and was recorded in 51.8% of the patients, while 33.2% showed only mild cognitive impairment.

In order to evaluate the stress factors, we selected 6 of the items of the original scale. Five of them were chosen due to their relationship with the information process, while the sixth offered a global view of the level of stress. The mean general stress score was 2.32 (σ=1.24), and failure on the part of the healthcare professional to answer the questions of the patients was cited by the latter as being the most stressing factor – with a mean score of 3.76 (σ=1.34).

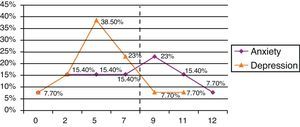

The descriptive analysis of the variables anxiety and depression showed 38.5% of the study sample to be free of anxiety, and 92.3% yielded low depression scores (Fig. 1).

In the descriptive analysis of the results obtained with the CITD, we grouped the items of the latter into 6 categories–each identifying the role which the patient considered should be played by those implicated in the information process and in decision taking.

Regarding the role assigned by the patients to their relatives, the mean total items score was 2.35 (σ=0.98). The highest score corresponded to the item “The relatives should be fully informed of the patient condition, treatment and prognosis”, with a mean score of 3.62 (σ=0.67). Likewise, the item “In the event a relevant decision must be made, I would like the doctor to ask my family, i.e., to allow them to participate in the decision” yielded a mean score of 2.82 (σ=0.96). However, the patients expressed less agreement with the items “If I am going to die, I would prefer to be told by my family” and “When there is bad news, the family should inform me, not the doctor”–with mean scores of 1.85 (σ=0.98) and 1.55 (σ=0.94), respectively.

Regarding the role which the patients consider they should play in the information process and in decision taking, the mean total items score was 2.83 (σ=1.06), i.e., higher than the score referred to the relatives. The items “In the event a relevant decision must be made, I would like the doctor to ask my opinion” and “Patients should be allowed to participate in the medical decisions referred to their treatment” yielded the same mean score of 3.34 (σ=0.93). The patients expressed less agreement with the item “Bad news should be withheld from the patient” – the mean score being 1.48 (σ=0.87).

The mean total items score referred to the role assigned by the critical patient to the physician was 3.16 (σ=1.03). On examining whether the last word in deciding corresponds to the physician, the mean score was found to be 2.72 (σ=1.13). It should be noted that 74.1% of the patients fully agreed with the affirmation that “If I am going to die, I would prefer to be told by the doctor”. On the other hand, the mean score referred to the role assigned by the critical patient to the psychologist was 2.86 (σ=1.05). According to 34.5% of the participants, the support of a psychologist would be of great help.

On examining the importance of decision taking for the patient, the item “I feel capable of participating in the taking of decisions that affect my health” yielded a mean score of 3.37 (σ=1.01), while the item “Being able to participate in a medical decision would be more of a burden for me than a privilege” yielded a mean score of 2.31 (σ=1.33). A total of 65.6% of the participants were in full agreement with the affirmation “I feel capable of participating in the taking of decisions”.

Table 1 shows the results of the analysis of the influence of the sociodemographic variables upon the cognitive, emotional, and subjective variables referred to the decision taking process. Analysis of the relationship among emotional variables, cognitive capacity, and the CITD score yielded a significant negative association between the level of depression in the ICU and cognitive capacity (p=0.048) (Table 2).

Pearson correlation coefficients between sociodemographic variables and MMSE, HADS and CITD scores.

| Influence of age | Influence of educational level | |||

| r | ρ | r | ρ | |

| Cognitive capacity–MMSEa | −0.53 | 0.004** | 0.42 | 0.027* |

| Anxiety level (HADS)b | 0.04 | 0.896 | −0.20 | 0.510 |

| Depression level (HADS)b | 0.26 | 0.385 | −0.23 | 0.435 |

| CITDc relatives | 0.21 | 0.281 | −0.10 | 0.604 |

| CITDc patients | −0.32 | 0.099 | 0.30 | 0.118 |

| CITDc physicians | 0.10 | 0.596 | 0.08 | 0.663 |

| CITDc psychologists | −0.10 | 0.587 | 0.19 | 0.306 |

| CITDc satisfaction | −0.10 | 0.586 | −0.05 | 0.794 |

| CITDc privilege | −0.47 | 0.009** | 0.33 | 0.075 |

Minimental test.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Questionnaire for subjective evaluation of the information process and decision taking in the hospital setting.

p≤0.05.

p≤0.01.

Pearson correlation coefficients between emotional variables (HADS) and cognitive variables (MMSE)–CITD.

| Anxiety level (HADS)b | Depression level (HADS)b | |||

| r | ρ | r | ρ | |

| Cognitive capacity – MMSEa | −0.53 | 0.059 | −0.55 | 0.048* |

| CITDc-relatives | −0.04 | 0.892 | 0.20 | 0.506 |

| CITDc-patients | 0.09 | 0.769 | −0.17 | 0.562 |

| CITDc-physicians | 0.22 | 0.471 | 0.10 | 0.736 |

| CITDc-psychologists | −0.08 | 0.775 | 0.11 | 0.704 |

| CITDc-satisfaction | 0.08 | 0.790 | −0.08 | 0.792 |

| CITDc-privilege | −0.27 | 0.373 | −0.05 | 0.868 |

Minimental test.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Questionnaire for subjective evaluation of the information process and decision taking in the hospital setting.

p≤0.05.

In order to analyze these differences between groups of individuals with high and low cognitive capacity, referred to subjective variables associated with the decision taking process (CITD), two groups of patients were established according to the MMSE score obtained. Group 1 (n=15) corresponded to patients with MMSE scores in the range of 16–24 points, while group 2 (n=14) corresponded to patients with an MMSE score in the range of 25–30 points (Table 3).

Differences between groups of patients with high and low cognitive capacity (MMSE) referred to the variables relating to decision taking capacity (CITD).

| Variable | Minimental 1 (n=15) | Minimental 2 (n=14) | t | p | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| CITDa relatives | 16.64 | 4.58 | 15 | 4.39 | 0.94 | 0.352 |

| CITDa patients | 21.57 | 7.30 | 25.61 | 5.51 | −1.61 | 0.119 |

| CITDa physicians | 6.92 | 1.26 | 5.30 | 1.75 | 2.77 | 0.010* |

| CITDa psychologists | 3 | 0.67 | 2.53 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 0.262 |

| CITDa satisfaction | 7.14 | 1.65 | 6 | 2.12 | 0.56 | 0.130 |

| CITDa privilege | 8.34 | 1.94 | 2 | 1.08 | −3.39 | 0.002* |

Questionnaire for subjective evaluation of the information process and decision taking in the hospital setting.

p≤0.01.

On examining the observation of patient competence in clinical practice, we find that there are no guidelines–though a number of practical principles have been established, such as definition of the source of authority, the securing of effective communication, the prompt availability of reliable information referred to the patient wishes, and respect for the patient rights.20

Considering that competence refers to how a capacity is applied to a given situation, and that this is more closely related to skill than to any stable cognitive characteristic,21 we have evaluated both the cognitive capacity of the patients and their skills in evaluating the surroundings or environment, and the roles which in their opinion are played by those implicated in the process.

The results of the CITD questionnaire indicate that the critical patient is in clear agreement with the idea that the family should receive full information on the patient condition, treatment, and prognosis. However, patients show only limited agreement with the idea that the family should have the last word or should be in charge of informing the patient of bad news. In some cases both the relatives and the clinicians underestimate the wishes of the patient, and this conclusion, drawn from the study published by Ciroldi et al.22 referred to consent to participation in research studies, may well be applicable to other areas such as decision taking in the ICU.23

Regarding the role which patients assign to themselves in the information process, 62% fully agree that they should be allowed to participate in the taking of decisions, and the same percentage firmly coincide that the patient should have the last word. Almost two-thirds of the participants fully agreed with the idea that they should be notified in advance if death is expected to occur. A study conducted in the primary care setting, using questionnaires similar to those contemplated by the CITD, has yielded similar results.24

With regard to the role which patients assign to the physician, three-quarters fully agree that it is preferable for bad news to be conveyed by the physician. Patients continue to attribute physicians with an important role in the communication process and in decision taking. The results of our study suggest that the relationship based on confidence that has always existed between patients and their physicians should be reinforced, and that this decision does not mean that the patient wishes and beliefs are no longer respected; rather, emphasis is placed on communication, mutual respect, and sincerity.25

According to the CITD findings, over one-half of the participants are quite or fully agreed with the availability of psychologist support in decision taking. Clinical psychologists are increasingly needed particularly in the ICU, due to the extreme situations facing patients, their relatives, and even the healthcare professionals.26

The studies published by Jorm et al.,27 O’Connor et al.28 and Manubens et al.29 have demonstrated a positive impact of educational level upon the MMSE score and a negative influence of age upon cognitive capacity. These studies differ from our own in terms of the type of patients involved, though our results nevertheless coincide. In effect, we observed a negative correlation between age and the MMSE score, and a positive correlation between educational level and the MMSE score–a higher educational level being associated with improved cognitive capacity. Furthermore, age exerted a negative influence referred to the variable “privilege” of the CITD, in that older patients regarded decision taking as more of a burden than a privilege.

The results obtained referred to the relationship among the emotional variables, the MMSE score, and the subjective variables related to decision taking point to an association between increased anxiety and depression and lessened cognitive capacity. Preventing and minimizing the causes of stress and providing the patient with comfortable conditions are effective measures for favoring a stable emotional state, which in turn facilitates decision taking.30

Although the anxiety and depression levels in our series were not very high, the literature reports that critical patients can suffer a range of psychological problems. In this context, anxiety, stress, and despair are cited as the main affective disorders–the expressed main need being the sensation of safety.31 The evaluation of competence should be adapted to the needs of each patient, and in this context the inclusion of a neuropsychological examination is advised.32

In the CoBaTrICE study,33 the patients considered it more important than their relatives to participate in decision taking and to be informed in detail, while for the relatives giving bad news with gentleness, and individualized treatment, were taken to be more important than for the patients. “Humaneness” was a quality sought by both the patients and their relatives, who often cited characteristics such as patience, closeness, and a sense of humor. Aspects considered to be improvable and related to previous experiences were especially the continuity of care by the same physician, and intercommunication among physicians.

Lastly, the professionals who attend critical cases have become accustomed to dealing with sedated and unconscious patients, with relatives who are scared and overwhelmed by incomprehensible situations that destabilize their lives, and in which decisions must be made quickly, since the life of the patient depends on them. To speak of humanization is easy, though putting it into practice is a challenge. Citing Simón-Lorda,34 it can be said that: “… Judgment of the capacity of a patient is always a probabilistic and prudential circumstance, not a scientific certainty. For this reason, none of the guidelines, instruments or protocols for assessing patient capacity can be taken to represent the “holy grail”–a magical solution capable of answering all doubts and of definitively putting an end to anguish. By using the available instruments we must accept the possibility of scientific, technical and ethical error. However, this does not mean that we should abandon the search for capacity-evaluating tools offering the best sensitivity and specificity possible”.

Our results indicate that the critical patient wishes to take part in the decision taking process, wants to be informed by the physician of any bad news, and wishes to have the last word regarding his or her disease process.

Our conclusions allow the following recommendations referred to clinical practice:

- 1.

Evaluate the decision taking process, not the result.

- 2.

Evaluate whether the patient understands all the relevant aspects of the decision and issues voluntary and informed consent.

- 3.

Improve our communication skills, respect the patient decisions, and implicate the relatives in patient care.

- 4.

Avoid making decisions in situations of crisis.

- 5.

Plan sessions on ethical discussions, identify the roles of those involved, develop coping strategies, and review the criteria used to resolve each situation.

- 6.

Improve the environment within the ICU, minimizing stressors and creating a comfortable setting for the patient.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Bernat-Adell MD, et al. ¿Es el paciente crítico competente para tomar decisiones? Razones psicológicas y psicopatológicas de la alteración cognitiva. Med Intensiva. 2012;36:416–22.