The appearance of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in 2019, and the severe pulmonary disease it causes in some patients with criteria of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) added to its significant mortality rate has encouraged the production of several studies in an attempt to know better these patients’ predictive factors of mortality.1,2 The huge avalanche of critically ill patients who required intensive care in a short period of time was one of the greatest challenges intensive medicine has ever had to face in its entire history.3 Therefore, we studied a cohort of critically ill patients with COVID-19 and moderate and severe ARDS according to the international standards.4 The demographic characteristics, risk factors, and inflammatory biomarkers at admission were studied as predictive factors of mortality.

This was a retrospective study that included clinical and analytical data from the electronic health records of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by CRP test admitted consecutively to the different ICU areas of 2 hospitals of the same sanitary region, and then classified as moderate and severe ARDS. Both the demographic data, the inflammatory biomarkers collected within the first 24 h, the hospital stay (days), and the final outcomes at the ICU setting were all included in a database. Given the observational and retrospective nature of the study, the hospital clinical research ethics committee concluded that the study could be conducted without the patients having to sign any informed consent forms.

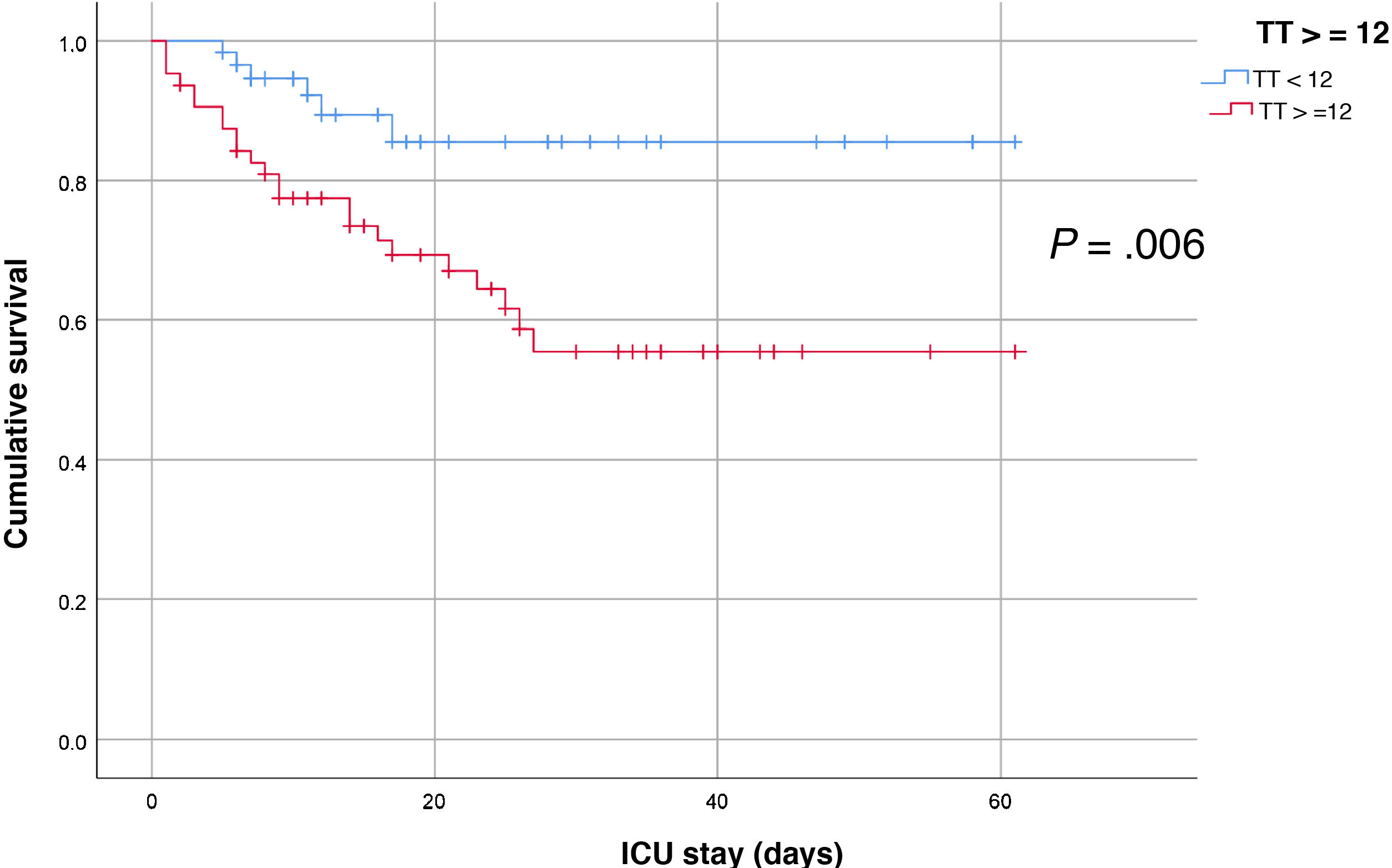

We used descriptive statistics and comparative analyses between living and dead patients using the chi-square test, the Student t-test or nonparametric estimation (Mann-Whitney U test), when appropriate. We designed Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the significant factors to eventually build a multiple logistic regression analysis to estimate the inflammatory biomarkers as predictive factors of mortality. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

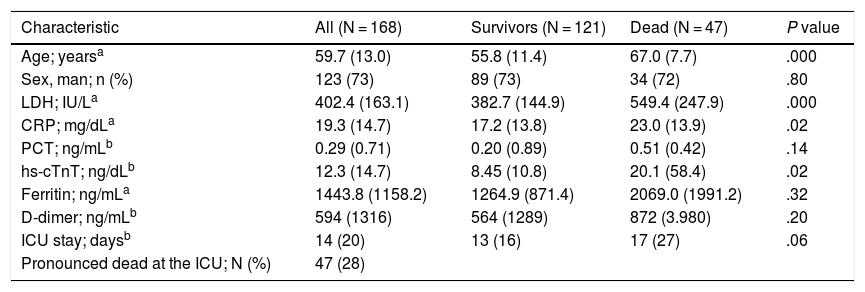

A total of 168 patients were included, all of them intubated and on invasive mechanical ventilation. When the analysis was performed all patients had been released from the different ICUs. We found that the patients who died were older compared to those who did not with significant differences, but not associated with the patients’ sex. The levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) were significantly higher in the patients who died compared to those who lived. We did not find any significant differences in the levels of procalcitonin (PCT), D-dimer or ferritin between the patients who died and those who lived.

The best multiple logistic regression analysis that included the variables of the bivariate analysis with P < .02 confirmed that age and LDH were predictive factors regardless of mortality in the cohort of critically ill patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 (Table 1).

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of critically ill patients with COVID-19.

| Characteristic | All (N = 168) | Survivors (N = 121) | Dead (N = 47) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age; yearsa | 59.7 (13.0) | 55.8 (11.4) | 67.0 (7.7) | .000 |

| Sex, man; n (%) | 123 (73) | 89 (73) | 34 (72) | .80 |

| LDH; IU/La | 402.4 (163.1) | 382.7 (144.9) | 549.4 (247.9) | .000 |

| CRP; mg/dLa | 19.3 (14.7) | 17.2 (13.8) | 23.0 (13.9) | .02 |

| PCT; ng/mLb | 0.29 (0.71) | 0.20 (0.89) | 0.51 (0.42) | .14 |

| hs-cTnT; ng/dLb | 12.3 (14.7) | 8.45 (10.8) | 20.1 (58.4) | .02 |

| Ferritin; ng/mLa | 1443.8 (1158.2) | 1264.9 (871.4) | 2069.0 (1991.2) | .32 |

| D-dimer; ng/mLb | 594 (1316) | 564 (1289) | 872 (3.980) | .20 |

| ICU stay; daysb | 14 (20) | 13 (16) | 17 (27) | .06 |

| Pronounced dead at the ICU; N (%) | 47 (28) |

| Multiple logistic regression analysis predictive of mortality at the ICU setting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive factor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age; years | 1.134 | 1.059 | 1.213 | .000 |

| CRP at admission; mg/dL | 1.037 | 0.999 | 1.076 | .057 |

| 1.002 | 1.009 | .002 | ||

| hs-cTnT; ng/dL | 1.008 | 0.997 | 1.020 | .158 |

The analysis of the survival curves for different risk factors clearly showed that hs-cTnT had significantly different curves. Therefore, hs-cTnT levels >12 ng/dL at the ICU admission were associated with a lower survival rate with P values = .006 (Fig. 1).

The results from our study show that age was associated with a higher mortality rate, which is consistent with the findings of former studies.1,2 The same thing happened with the elevated hs-cTnT levels that are probably associated with the myocardial damage caused by this disease that may lead to the catastrophic results described by Ruan et al. in their study on predictive factors of mortality in patients with COVID-19 and ARDS.5 This involvement in cardiac lesion has been very well reported in a recent review on the role that the heart plays in SARS-CoV-2 infections; this article6 suggests that SARS-CoV-2 has a direct effect on the myocardium added to the hypoxemia due to pulmonary lesion, and systemic inflammation. On the other hand, the levels of LDH at admission were independently associated with mortality, and they may have to do with a greater or lower cellular lesion in the lung tissue and other organs. Same as we did, Han et al.7 found that LDH was the only marker that significantly predicted ICU admissions, the development of ARDS, and mortality probably due to damage to the cellular cytoplasmatic membrane. All the biomarkers considered in the analysis play a more or less significant role of metabolic and immunological biomarkers that express the size of inflammation and cellular lesion.8 Finally, the mortality rate of our cohort including all patients with ARDS and on mechanical ventilation was 28%. A rate very similar to that reported by Ramírez et al.9 in their study that included similar patients and where mortality rate was as high as 26.5% in patients on mechanical ventilation.

These findings teach us an immediate clinical applicability, that age and LDH can anticipate the prognosis of this type of patients. Also, that elevated hs-cTnT levels are indicative that the cardiac function should be monitored much better for the proper administration of targeted therapies.

This study has limitations like the fact that it is a retrospective collection of data from only 2 centers with a cohort of patients who just flooded the ICUs and received pharmacological therapy and ventilation, not always homogeneously, and in different hospital wards. This produced a heterogeneous cohort of patients with very noticeable confounding factors. Another significant limitation is that severity scales (APACHE II) or markers like the IL-6 could not be collected in every patient. Despite of this, we believe that the statistical method used gave us robust and conclusive results for a specific healthcare area.

In conclusion, age, CRP, LDH, and hs-cTnT were significantly higher in patients who eventually died compared to those who lived on. However, in our model only age and LDH behaved as predictive factors regardless of mortality in critically ill patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 admitted to the ICUs.

Please cite this article as: Sirvent JM, Baro A, Morales M, Sebastian P, Saiz X. Biomarcadores predictivos de mortalidad en pacientes críticos con COVID-19. Med Intensiva. 2022;46:94–96.