Current guidelines recommend a risk-adjusted early invasive strategy (EIS) in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). The present study assesses the application if this strategy, the conditioning factors and prognostic impact upon patients with NSTEACS admitted to Intensive Cardiac Care Units (ICCU).

DesignA prospective cohort study was carried out.

SettingThe ICCUs of 8 hospitals in Catalonia (Spain).

PatientsConsecutive patients with NSTEACS between October 2017 and March 2018. The risk profile was defined by the European Society of Cardiology criteria.

InterventionsEIS was defined as the performance of coronary angiography within the first 6 h in patients at very high-risk or within 24 h in high-risk patients.

Outcome variablesMortality or readmission at 6 months.

ResultsA total of 629 patients were included (mean age 66.6 years), of whom 225 (35.9%) were at very high risk, and 392 (62.6%) at high risk. Most patients (96.2%) underwent an invasive strategy. EIS was performed in 284 patients (45.6%), especially younger patients with fewer comorbidities. These patients had a shorter ICCU and hospital stay, as well as a lesser incidence of ACS, revascularization and death or readmission at 6 months. After adjusting for confounders, the association between EIS and death or readmission at 6 months remained significant (hazard ratio: 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.45–0.97; p = 0.035).

ConclusionsThe EIS was performed in a minority of NSTEACS admitted to ICCU, being associated with better outcomes.

Las guías de práctica clínica recomiendan la estrategia invasiva precoz ajustada al riesgo (EIPAR) en pacientes con Síndrome Coronario Agudo sin elevación del segmento ST (SCASEST). El objetivo fue analizar la aplicación de la EIPAR, sus condicionantes e impacto sobre el pronóstico en pacientes con SCASEST ingresados en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Cardiológicos (UCIC).

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes prospectivo.

ÁmbitoUCIC de 8 hospitales en Cataluña.

PacientesPacientes consecutivos con SCASEST entre octubre 2017 y marzo 2018. El perfil de riesgo se definió mediante los criterios de la Sociedad Europea de Cardiología.

IntervencionesSe definió como EIPAR la realización de coronariografía en las primeras 6 horas en pacientes de muy alto riesgo o en 24 horas en pacientes de alto riesgo.

Variables de interés: Mortalidad/reingreso a los 6 meses.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 629 pacientes (edad media 66,6 años), 225 (35,9%) de muy alto riesgo, y 392 (62,6%) de alto riesgo. La estrategia invasiva fue mayoritaria (96,2%). La EIPAR se aplicó en 284 pacientes (45,6%), especialmente pacientes más jóvenes, con menos comorbilidades. Estos pacientes presentaron menor estancia en UCIC y hospitalaria, así como menor incidencia de SCA, revascularizaciones y menor incidencia de muerte/reingreso a 6 meses. Tras ajustar por factores de confusión, la asociación entre adherencia y muerte/reingreso a 6 meses persistió de manera significativa (razón de riesgos: 0,66 (0,45–0,97) p = 0,035).

ConclusionesLa EIPAR se aplica en una minoría de SCASEST ingresados en UCIC, asociándose con una menor incidencia de eventos.

The generalization of percutaneous coronary intervention has led to a gradual decrease in mortality due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in recent years, particularly in relation to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1 The clinical practice guides (CPGs) recommend an early invasive strategy (EIS) in the first 24 h in patients with high-risk non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS (NSTEACS), and in the first few hours in very high risk cases.2,3 The establishment of coordinated care poses an organizational challenge with a significant consumption of healthcare resources.4 Although adherence to the recommendations referred to ACS has increased in recent years,5,6 few data are available on the application of risk-adjusted EIS (RAEIS) in patients with NSTEACS in our setting.

The objectives of the present study were to: (a) analyze the application of RAEIS; (b) describe the factors associated to this management strategy; and (c) analyze its prognostic impact in a series of non-selected patients with NSTEACS admitted to Intensive Cardiac Care Units (ICCUs).

Patients and methodsStudy population and settingA prospective multicenter study was carried out in 8 ICCUs in Catalonia (Spain) over a period of 6 months (from 1 October 2017 to 31 March 2018). The study was endorsed and coordinated by the Acute Cardiological Care Working Group (Grup de Treball de Cures Agudes Cardiològiques) of the Catalan Society of Cardiology (Societat Catalana de Cardiologia), to which all the participating ICCUs are ascribed. The participating centers all have a general Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and an ICCU, with full availability (24 h, 7 days a week) of a hemodynamics laboratory. Furthermore, 6 of the centers have a heart surgery program and three have a heart transplant and short duration ventricular assist program. The present study was designed to analyze the 6-month prognostic impact of RAEIS in these patients.

Inclusion criteria: We prospectively and consecutively included those patients admitted to the ICCU of the participating centers with a diagnosis of NSTEACS, defined as the presence of chest pain consistent with ACS, and with at least one of the following: (1) electrocardiographic alterations suggestive of myocardial ischemia; and (2) the elevation of myocardial damage markers.

The only exclusion criterion was the impossibility of obtaining informed consent to participation in the study.

Data collectionThe data were collected by the local investigators on a prospective basis during patient admission, using specific and standardized forms. Demographic data were recorded, along with basal clinical characteristics, laboratory test data, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic information, the performance of coronary angiography and the time elapsed from admission to coronary angiography.

We also documented the in-hospital clinical course (treatments provided, need for invasive procedures, complications and in-hospital mortality). The CRUSADE7 and GRACE8 risk scores were calculated for each patient. The hemodynamic parameters (heart rate, systolic blood pressure) and Killip class were recorded upon admission to the ICCU. Creatinine clearance upon admission was calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula,9 and body surface area was recorded using the formula of Mosteller.10 With regard to troponin positivity, we did not consider those cases in which such anomalies were a consequence of revascularization.

The risk criteria of the European Society of Cardiology were used for the definition of patient risk profile.2 Very high risk patients were those with at least one of the following conditions: refractory angina, hemodynamic instability, cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias or cardiorespiratory arrest. Likewise, high risk patients were those with serum troponin elevation, diabetes mellitus or a GRACE score >140, without the presence of very high risk criteria.

Since this was an observational study, patient management was consistent with routine clinical practice, in accordance with the current recommendations. Antithrombotic therapy and coronary angiography were left to the criterion of the supervising medical team, in abidance with the intervention protocols applicable in each center. In the event of coronary angiography, the choice of vascular access, antithrombotic drugs and stents or other devices was left to the criterion of the operator.

We defined RAEIS as: (a) the performance of coronary angiography in the first 6 h of admission to the ICCU in very high risk patients; or (b) coronary angiography in the first 24 h in patients with high risk criteria.

Clinical follow-up was carried out after 6 months based on a physical presence interview, the review of case histories or telephone contact with the patient, relatives or reference physician. The primary endpoint of the study was the combination of overall mortality and readmission after 6 months of follow-up. We also recorded the incidence of reinfarction and new coronary revascularizations. The cause of death was established on the basis of the clinical criterion of the physician caring for the patient at the time of the event. Death of cardiac origin was taken to correspond to mortality attributable to myocardial infarction, sudden death or heart failure.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) in the absence of a normal distribution, as evidenced by the Shapiro-Wilk test. An analysis was made of the basal characteristics of the patients, their management, and the clinical course according to the application of RAEIS. Associations between categorical variables were explored using the chi-squared test, with correction for continuity where required. The analysis of the quantitative variables according to adherence to the recommendations was carried out with the Student t-test.

The impact of RAEIS upon the combination of death or readmission after 6 months was assessed by Cox regression analysis, taking the application of RAEIS as independent variable and the combination of death or readmission after 6 months as dependent variable. The potential confounders included in the analysis were required to meet the following conditions11: (a) exhibition of a statistically significant association (p ≤ 0.05) to both exposure (application of RAEIS) and effect (mortality or readmission after 6 months); (b) presentation of a clinically reasonable potential confounding effect between exposure and effect; and c) no role as intermediate variable in the relationship between both. In addition, the analysis included variables with a prior association to poorer prognosis in this scenario that did not meet the first of the mentioned criteria (gender, troponin positivity, left ventricular ejection fraction and the presence of multivessel coronary disease).

An accessory evaluation was also made of the factors associated to the application of RAEIS, leading to a propensity score matching analysis. A total of 348 patients were selected (174 subjected to RAEIS and 174 not subjected to RAEIS). The exploratory analysis of the characteristics of the groups showed no significant differences in terms of the main clinical parameters between the two cohorts. We subsequently analyzed the impact of RAEIS upon the incidence of death or readmission using Cox regression analysis with this selection of patients.

Kaplan Meier survival curves were plotted and the statistical significance of the differences was assessed using the log rank test. The statistical analysis was carried out using the PASW Statistics 18 package (Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical particularsInclusion in the study did not imply any change in the clinical management of the patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before inclusion in the study. The patient data were duly anonymized and processed according to current legislation, and the study protocol was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of the study coordinating center (Ref. IRB00005523).

ResultsA total of 629 patients with NSTEACS were admitted during the study period. Their mean age was 66.6 years, and the majority were males (76.8%, n = 483). Overall, the series presented a high risk profile, with a considerable percentage of conditions such as diabetes (37.8%, n = 238), previous stroke (8.9%, n = 56) or peripheral vascular disease (16.9%, n = 106). In turn, 18.9% of the patients (n = 119) presented signs of heart failure upon admission, and 91.3% (n = 574) showed serum troponin elevation. The mean GRACE score in the series was 141 (SD 36). A little over one-third of the patients (35.9%, n = 225) had very high risk criteria upon admission, while 62.6% (n = 392) presented high risk criteria.

The adoption of EIS during admission was the predominant practice (96.2%, n = 605). The information on the interval to coronary angiography was available in 603/605 patients (99.7%). The median time elapsed from ICCU admission to the performance of coronary angiography was 20 h (IQR 3–46 hours). Overall, RAEIS was applied in 45.6% of the cases (n = 284). This proportion was 54.6% in the patients at high risk, and lower in the patients with very high risk criteria (31.3%).

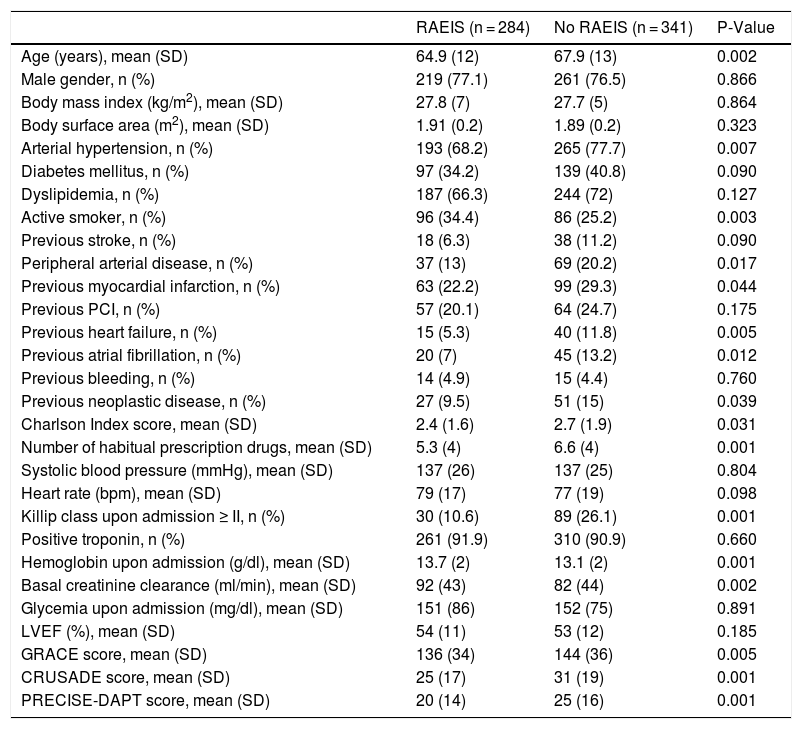

Clinical characteristics according to adherence to the recommendationsThe patients subjected to RAEIS were comparatively younger and showed a lesser prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, stroke or prior myocardial infarction (Table 1). They also had a lesser prevalence of atrial fibrillation, previous heart failure and antecedents of neoplastic disease, as well as a lower global comorbidity burden and fewer habitual prescription drugs. With regard to the clinical situation upon admission, the patients subjected to RAEIS showed a lesser presence of signs of heart failure upon admission, a tendency towards increased heart rate, and significantly lower scores on the GRACE and CRUSADE risk scales compared with the rest of the patients. They also had higher hemoglobin concentrations and glomerular filtration rates upon admission, without no significant differences between the two groups in terms of percentage positive troponin or left ventricular ejection fraction.

Clinical characteristics of the patients according to adherence to the recommendations at the time of the invasive strategy.

| RAEIS (n = 284) | No RAEIS (n = 341) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.9 (12) | 67.9 (13) | 0.002 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 219 (77.1) | 261 (76.5) | 0.866 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.8 (7) | 27.7 (5) | 0.864 |

| Body surface area (m2), mean (SD) | 1.91 (0.2) | 1.89 (0.2) | 0.323 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 193 (68.2) | 265 (77.7) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 97 (34.2) | 139 (40.8) | 0.090 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 187 (66.3) | 244 (72) | 0.127 |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 96 (34.4) | 86 (25.2) | 0.003 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 18 (6.3) | 38 (11.2) | 0.090 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 37 (13) | 69 (20.2) | 0.017 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 63 (22.2) | 99 (29.3) | 0.044 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 57 (20.1) | 64 (24.7) | 0.175 |

| Previous heart failure, n (%) | 15 (5.3) | 40 (11.8) | 0.005 |

| Previous atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 20 (7) | 45 (13.2) | 0.012 |

| Previous bleeding, n (%) | 14 (4.9) | 15 (4.4) | 0.760 |

| Previous neoplastic disease, n (%) | 27 (9.5) | 51 (15) | 0.039 |

| Charlson Index score, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.9) | 0.031 |

| Number of habitual prescription drugs, mean (SD) | 5.3 (4) | 6.6 (4) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 137 (26) | 137 (25) | 0.804 |

| Heart rate (bpm), mean (SD) | 79 (17) | 77 (19) | 0.098 |

| Killip class upon admission ≥ II, n (%) | 30 (10.6) | 89 (26.1) | 0.001 |

| Positive troponin, n (%) | 261 (91.9) | 310 (90.9) | 0.660 |

| Hemoglobin upon admission (g/dl), mean (SD) | 13.7 (2) | 13.1 (2) | 0.001 |

| Basal creatinine clearance (ml/min), mean (SD) | 92 (43) | 82 (44) | 0.002 |

| Glycemia upon admission (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 151 (86) | 152 (75) | 0.891 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 54 (11) | 53 (12) | 0.185 |

| GRACE score, mean (SD) | 136 (34) | 144 (36) | 0.005 |

| CRUSADE score, mean (SD) | 25 (17) | 31 (19) | 0.001 |

| PRECISE-DAPT score, mean (SD) | 20 (14) | 25 (16) | 0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; RAEIS: risk-adjusted early invasive strategy; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

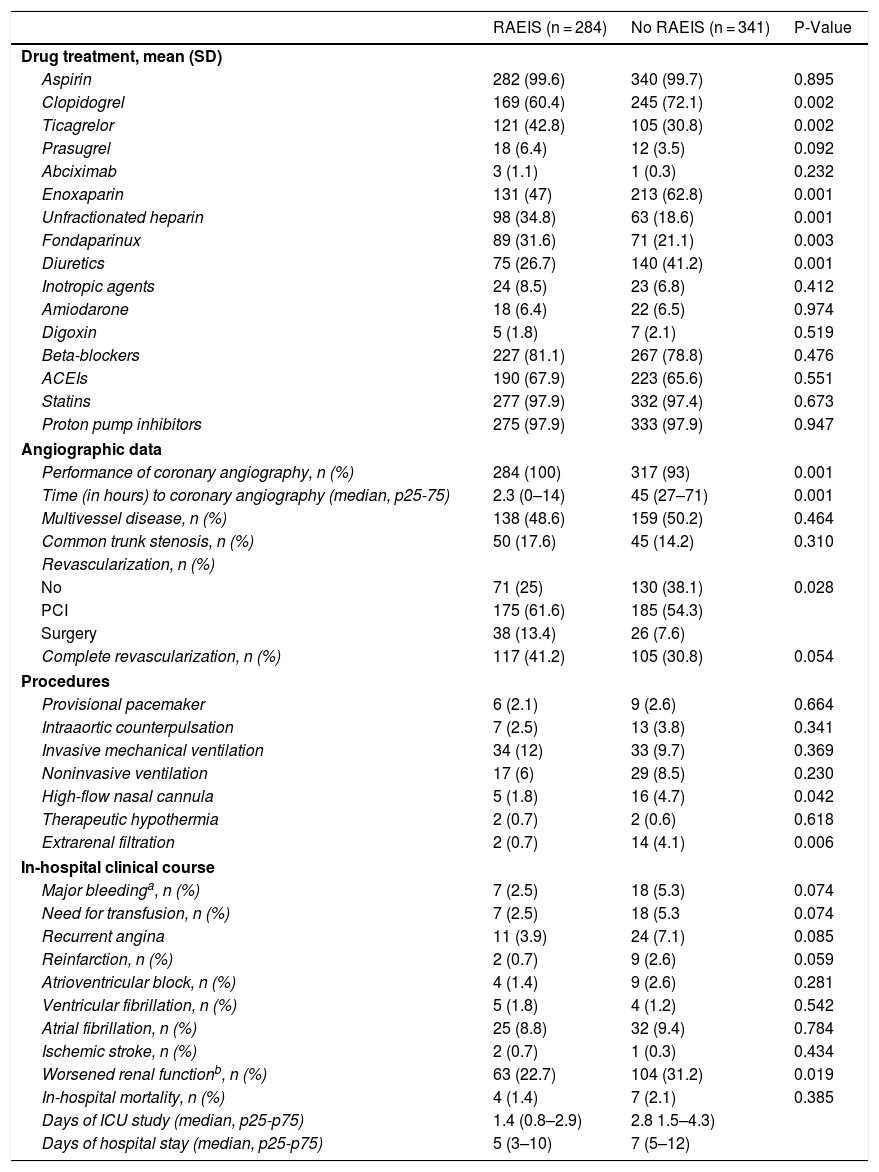

The patients subjected to RAEIS were less often treated with clopidogrel, enoxaparin and diuretics, and were more often treated with ticagrelor, unfractionated heparin and fondaparinux (Table 2).

Management and in-hospital evolution of the patients according to adherence to the recommendations at the time of the invasive strategy.

| RAEIS (n = 284) | No RAEIS (n = 341) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug treatment, mean (SD) | |||

| Aspirin | 282 (99.6) | 340 (99.7) | 0.895 |

| Clopidogrel | 169 (60.4) | 245 (72.1) | 0.002 |

| Ticagrelor | 121 (42.8) | 105 (30.8) | 0.002 |

| Prasugrel | 18 (6.4) | 12 (3.5) | 0.092 |

| Abciximab | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0.232 |

| Enoxaparin | 131 (47) | 213 (62.8) | 0.001 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 98 (34.8) | 63 (18.6) | 0.001 |

| Fondaparinux | 89 (31.6) | 71 (21.1) | 0.003 |

| Diuretics | 75 (26.7) | 140 (41.2) | 0.001 |

| Inotropic agents | 24 (8.5) | 23 (6.8) | 0.412 |

| Amiodarone | 18 (6.4) | 22 (6.5) | 0.974 |

| Digoxin | 5 (1.8) | 7 (2.1) | 0.519 |

| Beta-blockers | 227 (81.1) | 267 (78.8) | 0.476 |

| ACEIs | 190 (67.9) | 223 (65.6) | 0.551 |

| Statins | 277 (97.9) | 332 (97.4) | 0.673 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 275 (97.9) | 333 (97.9) | 0.947 |

| Angiographic data | |||

| Performance of coronary angiography, n (%) | 284 (100) | 317 (93) | 0.001 |

| Time (in hours) to coronary angiography (median, p25-75) | 2.3 (0–14) | 45 (27–71) | 0.001 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 138 (48.6) | 159 (50.2) | 0.464 |

| Common trunk stenosis, n (%) | 50 (17.6) | 45 (14.2) | 0.310 |

| Revascularization, n (%) | |||

| No | 71 (25) | 130 (38.1) | 0.028 |

| PCI | 175 (61.6) | 185 (54.3) | |

| Surgery | 38 (13.4) | 26 (7.6) | |

| Complete revascularization, n (%) | 117 (41.2) | 105 (30.8) | 0.054 |

| Procedures | |||

| Provisional pacemaker | 6 (2.1) | 9 (2.6) | 0.664 |

| Intraaortic counterpulsation | 7 (2.5) | 13 (3.8) | 0.341 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 34 (12) | 33 (9.7) | 0.369 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 17 (6) | 29 (8.5) | 0.230 |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 5 (1.8) | 16 (4.7) | 0.042 |

| Therapeutic hypothermia | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) | 0.618 |

| Extrarenal filtration | 2 (0.7) | 14 (4.1) | 0.006 |

| In-hospital clinical course | |||

| Major bleedinga, n (%) | 7 (2.5) | 18 (5.3) | 0.074 |

| Need for transfusion, n (%) | 7 (2.5) | 18 (5.3 | 0.074 |

| Recurrent angina | 11 (3.9) | 24 (7.1) | 0.085 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 9 (2.6) | 0.059 |

| Atrioventricular block, n (%) | 4 (1.4) | 9 (2.6) | 0.281 |

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 5 (1.8) | 4 (1.2) | 0.542 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 25 (8.8) | 32 (9.4) | 0.784 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0.434 |

| Worsened renal functionb, n (%) | 63 (22.7) | 104 (31.2) | 0.019 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 4 (1.4) | 7 (2.1) | 0.385 |

| Days of ICU study (median, p25-p75) | 1.4 (0.8–2.9) | 2.8 1.5–4.3) | |

| Days of hospital stay (median, p25-p75) | 5 (3–10) | 7 (5–12) | |

RAEIS: risk-adjusted early invasive strategy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

No significant differences were observed in the percentage of multivessel coronary disease or in the proportion of left common trunk involvement, though there was a higher frequency of coronary revascularization (fundamentally percutaneous and more often complete) in the patients subjected to RAEIS. We likewise observed no significant differences in the need for procedures during admission, with the exception of a lesser use of high-flow nasal cannulas and extrarenal filtration in the patients subjected to RAEIS (Table 2). These patients had a slightly lower incidence of bleeding complications, reinfarction and recurrent angina during admission, a lesser frequency of worsened renal function, and a shorter ICCU and in-hospital stay – with no significant differences in in-hospital mortality between the two groups (Table 2).

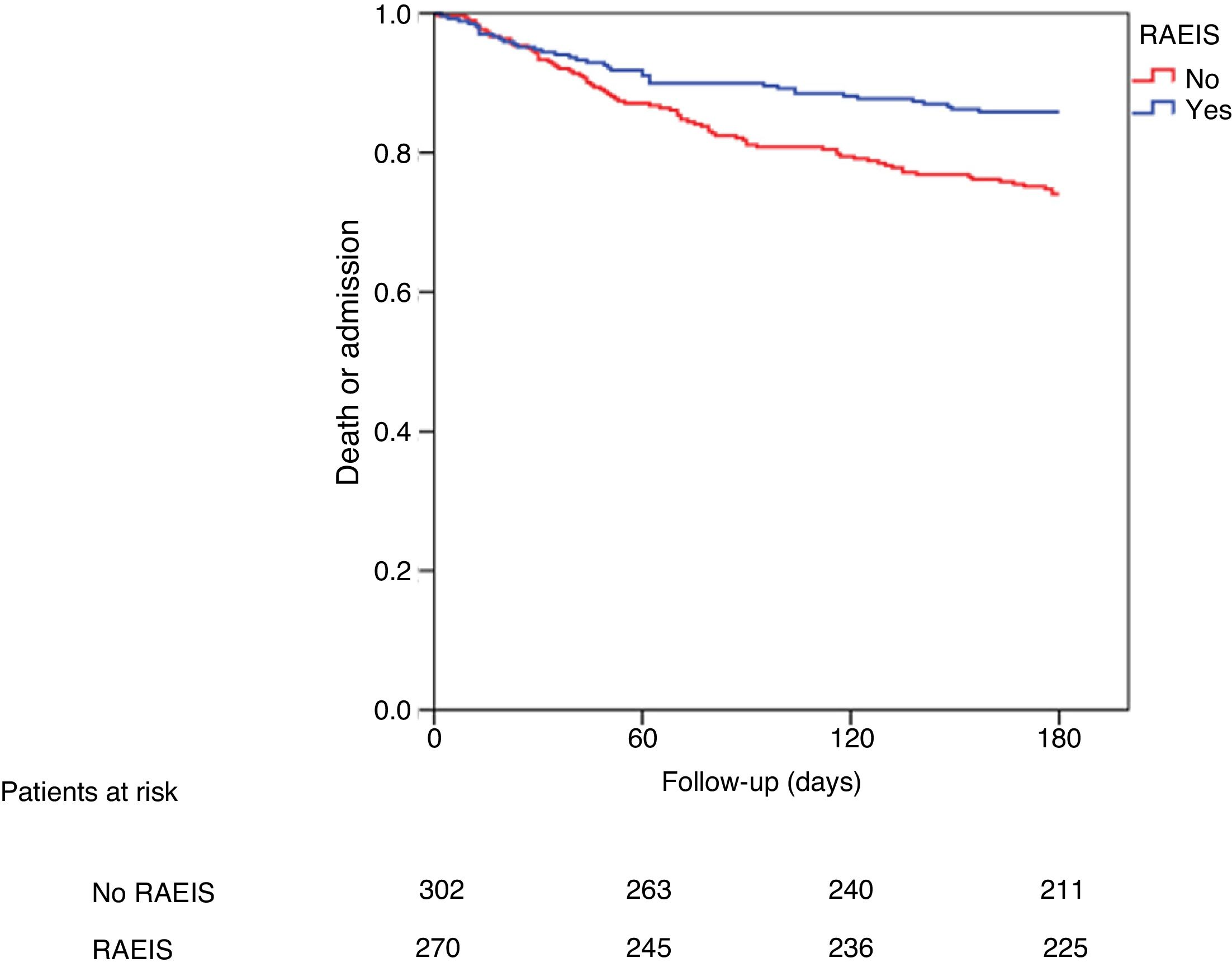

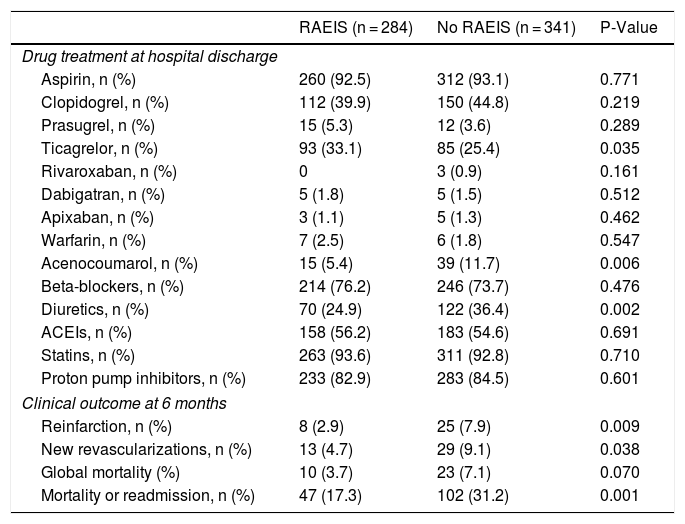

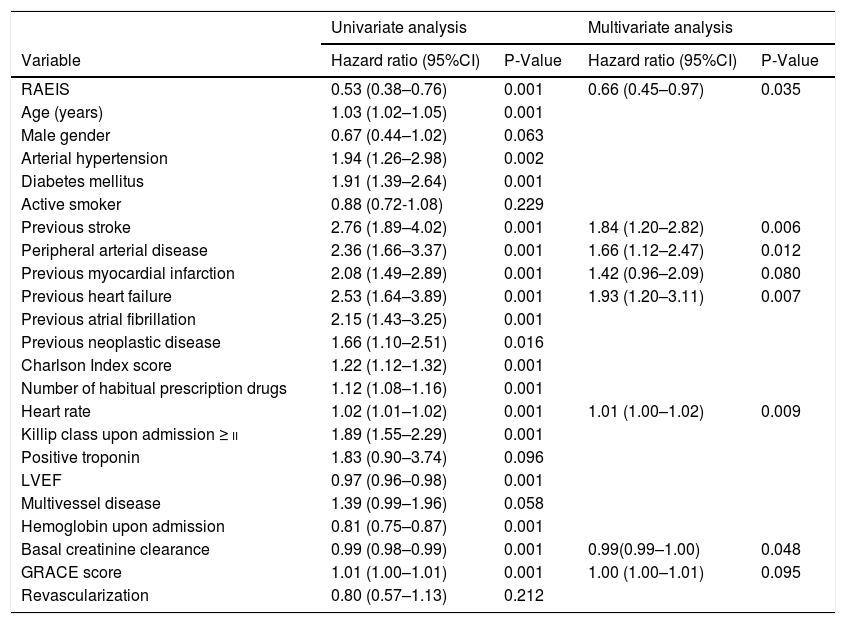

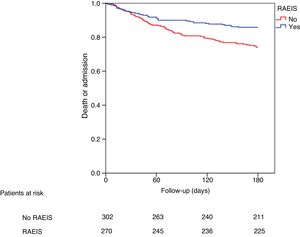

Impact of RAEIS upon patient prognosis at 6 monthsThe patients subjected to RAEIS showed better clinical outcomes after discharge (Table 3), with a lesser incidence of new ACS, a lesser need for new coronary revascularization, and a tendency towards lower in-hospital mortality. These patients likewise had a clearly lower incidence of the combination death or readmission at 6 months (relative risk [RR]: 0.53; 95% confidence interval [95%CI] 0.38–0.76; p = 0.001) (Table 4). After adjusting for potential confounders, the association between the application of RAEIS and the incidence of death or readmission remained statistically significant (RR: 0.66; 95%CI 0.45–0.97; p = 0.035) (Table 4). Fig. 1 shows the cumulative incidence of death or readmission at 6 months according to the application of RAEIS.

Management at discharge and posterior evolution according to adherence to the recommendations regarding the invasive strategy.

| RAEIS (n = 284) | No RAEIS (n = 341) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug treatment at hospital discharge | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 260 (92.5) | 312 (93.1) | 0.771 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 112 (39.9) | 150 (44.8) | 0.219 |

| Prasugrel, n (%) | 15 (5.3) | 12 (3.6) | 0.289 |

| Ticagrelor, n (%) | 93 (33.1) | 85 (25.4) | 0.035 |

| Rivaroxaban, n (%) | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 0.161 |

| Dabigatran, n (%) | 5 (1.8) | 5 (1.5) | 0.512 |

| Apixaban, n (%) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.3) | 0.462 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 7 (2.5) | 6 (1.8) | 0.547 |

| Acenocoumarol, n (%) | 15 (5.4) | 39 (11.7) | 0.006 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 214 (76.2) | 246 (73.7) | 0.476 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 70 (24.9) | 122 (36.4) | 0.002 |

| ACEIs, n (%) | 158 (56.2) | 183 (54.6) | 0.691 |

| Statins, n (%) | 263 (93.6) | 311 (92.8) | 0.710 |

| Proton pump inhibitors, n (%) | 233 (82.9) | 283 (84.5) | 0.601 |

| Clinical outcome at 6 months | |||

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 8 (2.9) | 25 (7.9) | 0.009 |

| New revascularizations, n (%) | 13 (4.7) | 29 (9.1) | 0.038 |

| Global mortality (%) | 10 (3.7) | 23 (7.1) | 0.070 |

| Mortality or readmission, n (%) | 47 (17.3) | 102 (31.2) | 0.001 |

RAEIS: risk-adjusted early invasive strategy; ACEIs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

Predictors of patient death or readmission at 6 months.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P-Value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P-Value |

| RAEIS | 0.53 (0.38–0.76) | 0.001 | 0.66 (0.45–0.97) | 0.035 |

| Age (years) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 0.001 | ||

| Male gender | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) | 0.063 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 1.94 (1.26–2.98) | 0.002 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.91 (1.39–2.64) | 0.001 | ||

| Active smoker | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | 0.229 | ||

| Previous stroke | 2.76 (1.89–4.02) | 0.001 | 1.84 (1.20–2.82) | 0.006 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2.36 (1.66–3.37) | 0.001 | 1.66 (1.12–2.47) | 0.012 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 2.08 (1.49–2.89) | 0.001 | 1.42 (0.96–2.09) | 0.080 |

| Previous heart failure | 2.53 (1.64–3.89) | 0.001 | 1.93 (1.20–3.11) | 0.007 |

| Previous atrial fibrillation | 2.15 (1.43–3.25) | 0.001 | ||

| Previous neoplastic disease | 1.66 (1.10–2.51) | 0.016 | ||

| Charlson Index score | 1.22 (1.12–1.32) | 0.001 | ||

| Number of habitual prescription drugs | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 0.001 | ||

| Heart rate | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.009 |

| Killip class upon admission ≥ ii | 1.89 (1.55–2.29) | 0.001 | ||

| Positive troponin | 1.83 (0.90–3.74) | 0.096 | ||

| LVEF | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.001 | ||

| Multivessel disease | 1.39 (0.99–1.96) | 0.058 | ||

| Hemoglobin upon admission | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) | 0.001 | ||

| Basal creatinine clearance | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.001 | 0.99(0.99–1.00) | 0.048 |

| GRACE score | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.095 |

| Revascularization | 0.80 (0.57–1.13) | 0.212 | ||

RAEIS: risk-adjusted early invasive strategy; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; CI: confidence interval.

On the other hand, the propensity score matching analysis showed an independent association between the application of RAEIS and a lesser incidence of death or readmission at 6 months (HR 0.57; 95%CI 0.36–0.89; p = 0.022).

DiscussionThe main findings of the present study are: (a) RAEIS was applied in a minority (45.6%) of the patients with NSTEACS admitted to the ICCU; (b) application of the strategy was more common in younger patients with a lower comorbidity burden and a lesser global risk profile; and (c) the application of RAEIS was associated to a lower incidence of events during follow-up.

The EIS approach in patients with NSTEACS has been shown to offer prognostic benefits.12,13 Accordingly, the CPGs recommend an invasive approach in the great majority of these patients, with adaptation of the earliness of EIS to the patient risk profile.2 The available data on the application of RAEIS in clinical practice in our setting are very limited.

The results of our study show that less than half of the patients admitted to the ICCU due to NSTEACS undergo invasive coronary angiography within the recommended timeframes. Interestingly, the patients subjected to RAEIS were comparatively younger, with fewer comorbidities and lower GRACE scores. This apparent paradox has been widely described before, though fundamentally in patients admitted to conventional hospital wards.5,6 The information available on patients admitted to critical care units is much more limited.14–16 The location of patients with NSTEACS in care units other than the ICCU is often conditioned by a certain age profile and by comorbidities. Furthermore a cardiological high risk profile (high GRACE scores, acute heart failure, positive troponin) often coexists with an “untreatable” risk component (advanced age, comorbidities, frailty).17,18 In this regard, mention must be made of the relatively young age of the included patients and the low percentage of women compared with other series.19 In our opinion, one of the main strengths of the present study is that it exclusively refers to consecutive patients admitted to an ICCU, and who in theory are fully amenable to high complexity invasive measures.

The application of EIS was highly prevalent in our series (96.2%), confirming the rising trend in this respect observed in different Spanish registries in recent years.5,6 Other factors such as the level of hospital complexity and the availability of cardiological resources can also condition the percentage of patients subjected to EIS.20 All the centers participating in our study are third-level institutions with the availability of a hemodynamics laboratory – a fact that undoubtedly contributed to the high EIS rate recorded in our series. Likewise, the percentage of patients subjected to percutaneous revascularization in this study was significantly higher than reported elsewhere.5,6

The mentioned recommendations in patients with NSTEACS are based on a series of clinical trials involving a high degree of patient selection and the enrolment of individuals with a relatively low risk profile.21–23 The extrapolation of their findings therefore may prove questionable. In our opinion, another strong point of the present study is that it included consecutive patients admitted to this clinical setting from all over the region of Catalonia (Spain) during a period of 6 months, thereby offering a reliable representation (in our opinion) of routine clinical practice in our setting.

Data on the ideal timing of EIS according to risk are more limited. Specifically, the recommendation to adopt an early strategy in patients at high risk is based on the results of the TIMACS study.24 This trial randomized 3031 patients with NSTEACS to either an early invasive strategy (<12 h) or a later invasive strategy (>36 h) - the primary study endpoint being the combination of death, myocardial infarction or stroke at 6 months. Coronary angiography was performed after an average of 14 h in the early invasive strategy group. Although no decrease was observed in the incidence of the primary endpoint between the two groups, there was a reduction of the secondary endpoint combining death, infarction or refractory ischemia at 6 months. Likewise, the analysis by subgroups revealed a decrease in the primary endpoint in those patients at greater risk (GRACE score >140).

More recently, the VERDICT study25 randomized 2147 patients with NSTEACS to an early invasive strategy (<12 h) versus a more delayed invasive strategy (48–72 h) - the primary endpoint being the combination of death, myocardial infarction, hospitalization due to recurrent ischemia, or hospital admission due to heart failure. Coronary angiography was performed after an average of 4.7 h in the early invasive strategy group. This study likewise observed no significant differences in the incidence of the primary endpoint between the two groups, though the differences were greater in the subgroup of patients at higher risk (GRACE score >140) (p-value for the interaction = 0.023).

Lastly, Jobs et al.26 performed a meta-analysis including 5324 patients with NSTEACS belonging to 8 clinical trials. Here again, the benefits in terms of mortality associated to EIS were limited to decreased mortality only in the patients with a GRACE score >140, diabetes mellitus, age >75 years and the elevation of myocardial damage markers.

The results of our study also reflect an improved clinical course in the patients subjected to RAEIS. In addition to the fact that this is an observational study, the main difference between our series and the other mentioned publications is that it includes risk stratification in line with the recommendations of the guides (i.e., earlier EIS in the patients at higher risk) within the group of subjects in which RAEIS was applied. It should be noted that the patients included in our registry had a high risk profile, since 35.9% met very high risk criteria and 62.6% had high risk criteria.3

The GRACE score is associated to the probability of presenting more severe and complex coronary disease (involvement of the common trunk, proximal anterior descending artery or multivessel disease),27 which could explain improvement of the patient prognosis when early intervention is carried out. In the present study, the mean GRACE score was 141, which is very similar to the score of the patients included in the VERDICT trial.25 The fact that the patients subjected to RAEIS had a higher revascularization rate despite the absence of differences in the proportion of multivessel coronary disease could indicate a lesser complexity of coronary disease in this subgroup – a notion that would be consistent with the lower GRACE score recorded in these patients. Furthermore, the patients subjected to RAEIS showed a lesser incidence of new ACS and of new revascularizations, and a clearly lower incidence of death or readmission at 6 months. This could be related to the high risk profile of the patients of our study. Although the groups were scantly comparable in terms of their global risk profile, the exhaustive adjusted analysis performed revealed an association between the application of RAEIS and the incidence of events at 6 months.

The application of RAEIS in our setting poses some difficulties, due in part to the great time dedicated by the hemodynamics laboratories to activities such as the dissemination of primary percutaneous coronary intervention practices in Spain in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)28 or the growing indication of other types of procedures (percutaneous aortic prosthesis implantation, revascularization of chronic coronary occlusions).29 In view of the above, the full application of RAEIS in patients with NSTEACS requires an important organizational and logistic effort, with a notorious investment of healthcare resources (between-hospital transfer systems, material and staff provisions of hemodynamics laboratories). In our opinion, the results of the present study underscore the need to advance in this direction with a view to optimizing the management and prognosis of these patients.

This study has some limitations, such as the size of the subgroups or the moderate number of events. Furthermore, the fact that this is an observational study does not allow us to rule out the presence of a certain selection bias or a potential effect of non-analyzed confounders (particularly taking into account the considerable differences between the patients subjected and not subjected to RAEIS). On the other hand, in relation to RAEIS in the very high risk patients, the considered time interval to coronary angiography was less strict than the two hours stipulated by the current recommendations. The data corresponding to some potentially relevant variables of medical treatment (earliness of treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or beta-blockers, duration of anticoagulation) were not fully available. Lastly, the duration of follow-up of 6 months could have been insufficient to detect a stronger impact of RAEIS upon the patient prognosis.

Despite the above, in our opinion this study offers relevant and novel information on the application of RAEIS in patients with NSTEACS admitted to the ICCU in our setting, it’s determining factors, and its possible impact upon the clinical outcomes. The optimization of management of patients with this high risk profile could have notorious medical, economic and social consequences.

In conclusion, RAEIS was applied in a minority of patients with NSTEACS admitted to the ICCU. The patients subjected to this strategy were younger, with fewer comorbidities and presented a lesser global risk profile. The patients subjected to RAEIS had a lower incidence of events during the follow-up.

AuthorshipMG, SM, CT, GB, DV, TO, JSR, JC, IH, MPR: data collection and critical review of the article.

IL, AA: data collection and analysis; drafting of the manuscript.

JAGH, JA, AS, CG, JO, RA, AC: critical review and intellectual contribution to the article.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Llaó I, Gómez-Hospital JA, Aboal J, Garcia C, Montero S, Sambola A, et al., en representación de los investigadores del Grup de Treball de Cures Agudes Cardiològiques de la Societat Catalana de Cardiologia. Estrategia invasiva precoz ajustada al riesgo en pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación de segmento ST en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Cardiológicos. Med Intensiva. 2020;44:475–484.