Idiopathic hyperammonemic encephalopathy is characterized by an altered level of consciousness associated with elevated blood ammonia without an identifiable cause. It frequently progresses to coma and is associated with high mortality.1

Combination therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin is widely used in advanced solid tumors, particularly bladder cancer, non–small cell lung cancer, pleural mesothelioma, and biliary tract tumors, including cholangiocarcinoma. This regimen has demonstrated efficacy in terms of tumor response and survival, with a generally predictable toxicity profile.2 The most common adverse reactions include myelosuppression, nausea, vomiting, and renal or hematologic toxicity. However, hyperammonemic encephalopathy is not listed among the common adverse effects, which may delay its diagnosis.3

This is the case of a patient with cholangiocarcinoma on gemcitabine (995 mg) and cisplatin (30 mg) who developed severe hyperammonemic encephalopathy 14 days after the 3rd cycle of chemotherapy. He presented to the oncology clinic with disorientation, incoherent speech, and progressive impairment of consciousness. In the following hours, the patient progressed to coma. Lab test results revealed ammonia of 240 µmol/L (normal < 75 µmol/L), with normal hepatic, renal, and electrolyte function. Infectious causes were excluded with cultures and serologies; structural causes with neuroimaging; and alternative metabolic causes with additional testing. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he required orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation due to severe altered consciousness. Treatment was initiated with nasogastric lactulose, rifaximin, and intensive supportive care. The clinical course was favorable, with progressive neurologic improvement paralleling the decline in ammonia levels, which normalized on day 3. No concomitant hepatotoxic drugs or supplements were identified. In the absence of other causes, the most likely diagnosis was hyperammonemic encephalopathy due to gemcitabine or cisplatin therapy. The favorable outcome, without another demonstrable cause, supported this hypothesis.

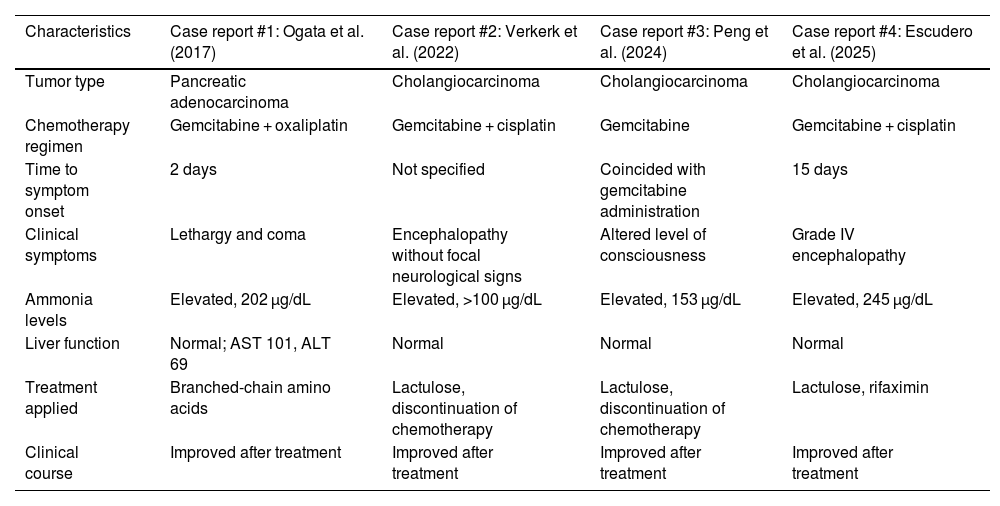

Although rare, the association between hyperammonemia and gemcitabine therapy has been reported in the recent medical literature. Verker et al. described a similar case in 2022 in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma treated with the same regimen, hypothesizing mitochondrial toxicity with urea cycle dysfunction.4 Similarly, Peng et al. (2024) reported hyperammonemic encephalopathy after gemcitabine in the absence of liver disease. In both cases, as in ours, cisplatin may have played a contributory role, as its subclinical renal toxicity can hinder ammonia excretion or potentiate the neurometabolic effects of gemcitabine.5 In addition, cisplatin has been proposed to alter the gut microbiota and increase bacterial ammonia production, promoting intestinal dysbiosis as a possible contributory mechanism.6 Although the individual role of each drug is not clearly established, the recurrence of the condition in similar contexts suggests a synergistic effect.7 Ogata et al. (2017) reported a case with oxaliplatin and gemcitabine, further supporting the hypothesis of cross-toxicity between alkylating agents and antimetabolites.8Table 1 illustrates published cases in the literature linking gemcitabine–cisplatin therapy and idiopathic hyperammonemic encephalopathy. These findings, although rare, suggest a possibly underdiagnosed entity.

Published cases in the literature of idiopathic hyperammonemic encephalopathy related to gemcitabine therapy.

| Characteristics | Case report #1: Ogata et al. (2017) | Case report #2: Verkerk et al. (2022) | Case report #3: Peng et al. (2024) | Case report #4: Escudero et al. (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor type | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Cholangiocarcinoma | Cholangiocarcinoma | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| Chemotherapy regimen | Gemcitabine + oxaliplatin | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Gemcitabine | Gemcitabine + cisplatin |

| Time to symptom onset | 2 days | Not specified | Coincided with gemcitabine administration | 15 days |

| Clinical symptoms | Lethargy and coma | Encephalopathy without focal neurological signs | Altered level of consciousness | Grade IV encephalopathy |

| Ammonia levels | Elevated, 202 µg/dL | Elevated, >100 µg/dL | Elevated, 153 µg/dL | Elevated, 245 µg/dL |

| Liver function | Normal; AST 101, ALT 69 | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Treatment applied | Branched-chain amino acids | Lactulose, discontinuation of chemotherapy | Lactulose, discontinuation of chemotherapy | Lactulose, rifaximin |

| Clinical course | Improved after treatment | Improved after treatment | Improved after treatment | Improved after treatment |

In cancer patients, altered consciousness is often attributed to tumor progression, infection, psychotropic medications, or electrolyte disturbances. This case underscores the need for a high index of suspicion when neurologic symptoms occur in cancer patients, even in the absence of hepatic risk factors.

Evidence in our setting on the clinical profile of ICU patients, their baseline status, in-hospital course, and outcomes such as mortality remains scarce.9 Notably, the work of Olaechea et al., through the ONCOENVIN registry, shows that coma is the neoplastic complication prompting ICU admission in 4.5% of patients.10 It therefore seems reasonable to consider monitoring ammonia levels in patients who develop neurologic symptoms after gemcitabine–cisplatin therapy, and to reassess continuation of treatment if this toxicity is confirmed. Of note, the prognosis of critically ill oncology patients has improved markedly over the past decade due to multidisciplinary team integration, optimization of organ support, and early identification of complications.11

Future studies should evaluate the true prevalence of this complication and potential predisposing factors. Meanwhile, dissemination of such cases may help raise awareness of a potentially reversible but still underdiagnosed toxicity.

CRediT authorship contribution statementThe review was conducted as follows: two authors reviewed the case reports; two authors conducted the literature search and review on gemcitabine and its adverse effects; and the remaining two authors drafted and finalized the scientific letter. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNo artificial intelligence was used at any stage of the manuscript preparation process.

FundingNone declared.

None declared.