To identify knowledge, skills and attitudes among physicians and nurses of adults’ intensive care units (ICUs), referred to advance directives or living wills.

DesignA cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out.

SettingNine hospitals in the Community of Madrid (Spain).

ParticipantsPhysicians and nurses of adults’ intensive care.

InterventionsA qualitative Likert-type scale and multiple response survey were made.

VariablesKnowledge, skills and attitudes about the advance directives. A descriptive statistical analysis based on percentages was made, with application of the chi-squared test for comparisons, accepting p<0.05 as representing statistical significance.

ResultsA total of 331 surveys were collected (51%). It was seen that 90.3% did not know all the measures envisaged by the advance directives. In turn, 50.2% claimed that the living wills are not respected, and 82.8% believed advance directives to be a useful tool for health professionals in the decision making process. A total of 85.3% the physicians stated that they would respect a living will, in cases of emergencies, compared to 66.2% of the nursing staff (p=0.007). Lastly, only 19.1% of the physicians and 2.3% of the nursing staff knew whether their patients had advance directives (p<0.001).

ConclusionsAlthough health professionals displayed poor knowledge of advance directives, they had a favorable attitude toward their usefulness. However, most did not know whether their patients had a living will, and some professionals even failed to respect such instructions despite knowledge of the existence of advance directives. Improvements in health professional education in this field are needed.

Explorar los conocimientos, habilidades y actitudes de los médicos y enfermeras de las unidades de cuidados intensivos de adultos sobre las instrucciones previas (IP) o documento de voluntades anticipadas (DVA).

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo, transversal.

ÁmbitoNueve hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid.

ParticipantesMédicos y enfermeras de cuidados intensivos de adultos.

IntervencionesCuestionario anónimo, autocumplimentado con variables dicotómicas y escala tipo likert.

VariablesConocimientos, habilidades y actitudes sobre las IP.

Análisis estadístico descriptivo con porcentajes y prueba de ji-cuadrado, tomando como significativos valores p<0,05.

ResultadosRespondieron al cuestionario 331 profesionales (tasa de respuesta del 51%). Además de los sociodemográficos, se obtuvo que el 90,3% no conoce todas las medidas que contemplan las IP. El 82,8% opina que el DVA es un instrumento útil para los profesionales en la toma de decisiones. El 50,2% opina que los DVA no se respetan. El 85,3% de los médicos respetaría el DVA de un paciente en caso de urgencia vital, frente al 66,2% de las enfermeras (p=0,007). Solo el 19,1% de los médicos y el 2,3% de las enfermeras conoce si los pacientes que llevan a su cargo poseen un DVA (p<0,001).

ConclusionesAunque los profesionales sanitarios muestran conocimientos escasos sobre las IP, presentan una actitud favorable hacia su utilidad. Sin embargo, la mayoría no conocen si los pacientes que están a su cargo poseen un DVA e incluso algunos profesionales a pesar de conocerlo, en caso de urgencia vital no lo respetarían. Se hace necesaria una mayor formación sobre las IP.

Advance directions or living wills (AD/LW) are a series of documents in which patients state how they wish to die or be treated at the end of life, with the purpose of having their wish respected.1

These documents have evolved over the years, adopting different forms from the origin (the “living will”; United states, 19672) to the introduction of a new trend in 1998, called “advance care planning”. In this context, the LW is defined as a tool resulting from a broad communication process,1,3–7 that requires health professionals to have the training needed to afford improved care at the end of life. A number of studies8–12 have found that inadequate training referred to end of life care, particularly in the intensive care unit (ICU), complicates the acquisition of communication attitudes and skills, patient care, and respect for the LW (with all the measures it contemplates) and, in sum, makes it difficult to preserve dignity in the patient dying process.

In Spain,3,7 the right of patients to participate in decisions affecting their life is recognized by the Spanish Constitution,13 which refers to freedom (art. 1), dignity and the development of personality (art. 10), and ideological freedom (art. 16), as constitutional rights. However, it was in January 2000, with the “Oviedo consensus”,14 when legal recognition of these documents was started, and following the amendment to the General Health Act,15 the regulation embodied in Act 41/2002 on patient autonomy16 and rights and obligations in matters of clinical documentation and information was approved. This is a basic state law, and the first to define AD.17 In 2007, with the introduction of Spanish Royal Decree 124/2007, the National Registry of Advance Directions was created to allow health professionals to access the contents referred to AD from any point in Spain.

However, although the different Spanish Autonomous Communities have developed informative guides on AD, there are important shortcomings in knowledge on the part of both the professionals and citizens,1,3,7,18–20 and little research has been conducted in this field. Specifically, we have not found any previous studies on the competences of the health professionals in relation to AD or LW in the ICU. We therefore decided to carry out the present study, for it is in these Units where the respect of patient wishes and desires is particularly important – since most such patients are admitted under conditions of disability, and are therefore at an increased risk of not having such wishes met.

Thus, the present study was designed to analyze the competences (knowledge, skills and attitudes) of physicians and nurses in the ICUs of the Community of Madrid, referred to AD or LW.

Patients and methodsA cross-sectional, descriptive observational study was carried out in nine hospitals of the Community of Madrid (Spain) between October and December 2010. A convenience sample was interviewed, comprising all the physicians and nurses of the adult ICUs of the following Hospitals: Infanta Leonor, Doce de Octubre, Clínico San Carlos, Getafe, Móstoles, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Gómez Ulla and Clínica Anderson. The selection of hospitals considered differences in terms of structure (dimensions, antiquity), management (public, public with private management, private and military), level of care (secondary, tertiary) and specialty (oncological, polytrauma, cardiac, coronary, polyvalent), with the aim of ensuring greater representation (Table 1).

Characteristics of the hospitals.

| Hospitals | Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions (no. beds) | Management (public/private) | Healthcare level (secondary/tertiary | ICU specialization | ICU units | |

| Hospital 1 | 1100–1200 | Public | Tertiary | Medical-surgical/neuropolytrauma/coronary | 2 |

| Hospital 2 | 1300–1400 | Public | Tertiary | Medical-surgical/neuropolytrauma | 3 |

| Hospital 3 | 500–550 | Private | Tertiary | Medical-surgical/coronary | 1 |

| Hospital 4 | 400–450 | Public | Secondary | Medical-surgical/coronary | 1 |

| Hospital 5 | 75–100 | Private | Secondary | Medical-surgical/oncological | 1 |

| Hospital 6 | 650–700 | Public/private | Tertiary | Medical-surgical/trauma | 1 |

| Hospital 7 | 250–270 | Public/private | Secondary | Medical-surgical/coronary | 1 |

| Hospital 8 | 600–650 | Public | Tertiary | Medical-surgical/major burns | 2 |

| Hospital 9 | 600–650 | Public/private | Tertiary | Medical-coronary/surgical | 2 |

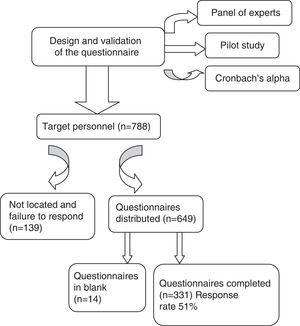

The total or target population consisted of 788 subjects (among physicians and nurses). Calculation of the sample size according to the target population, and assuming maximum indetermination (expecting a proportion of 50%), yielded No.=341 participants with a confidence level of 95% and an estimated precision of 4%.

A structured and self-administered questionnaire was designed specifically for this study, addressing 19 items (6 sociodemographic items, 10 dichotomic items, 2 items scored using three-point Likert-type scales, and one multiple response item). Construction of the questionnaire was based on the most relevant aspects of knowledge contained in Act 41/2002 referred to autonomy16 and medical concepts20–23 (Table 2); the skills and attitudes referred to the general and specific competences defined in the guide of the Spanish National Agency for the Evaluation of Quality and Accreditation (Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación, ANECA); and the recommendations of the Nursing and Medical Colleges and of the Bioethics Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva Crítica y Unidades Coronarias, SEMICYUC).22

Definitions and terminological specifications of living wills.

| Term | Concept |

|---|---|

| Living will | The first term used to define the documents referred to the care which a patient wishes to receive at the end of life. It represents an anticipatory description of the treatments which should or should not be applied when the patient reaches the terminal stage.19 |

| Advance directives | Sui generis legal mandates (wills of private origin, recognized by law, and which may have a legal effect) addressed to the physician (on a nominate or innominate basis), who will be assigned to interpret the desire of the patient or to share it, when the patient designates a third person.20 |

| Prior instructions | A stated will, regarded as a unilateral legal document (testament),17 drafted on the basis of the following criteria1,7,17,21–23: - It must always be in writing. - It can be issued in the presence of three witnesses, a notary public, or the administration (national registry). - Possibility of free revocation, without time limits, and in writing. - It must be incorporated to the case history. The measures contemplated are21–23: - The vital principles or criteria that must guide care decision. - The concrete situations in which the document is to be taken into account. - The instructions and limits referred to medical actions. - The wish to not be informed. - The destination of body and organs. - The possibility of designating legal representatives. The document has a series of limitations, such as: instructions contrary to law, lex artis and assumptions of fact. Due registry in the case history is required.1,3,7,17,21,22 The aim is to respect patient autonomy, dignity and freedom, when a situation of disability prevents the patient from deciding personally1,3,7; increase patient knowledge of the disease7,16; improve the clinical relationship;21,22; and facilitate interpretation of the ethical values of the patient.21,23 |

The design and validation of the questionnaire ensured its validity and reliability after undergoing the following procedures:

- 1.

Assessment by a panel of experts composed of intensive care physicians and nurses with expertise in bioethics.

- 2.

Conduction of a pilot study in Hospital Clinico San Carlos, involving a representative sample of the study population.

- 3.

Statistical verification: reliability of the survey, based on Cronbach's alpha, with an index of 0.725.

The study variables comprised sociodemographic data, and information referred to knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Description of the intervention: We first contacted the Heads of Department and nursing supervisors of all the centers with the purpose of explaining the study and obtaining approval of the project in the different Units. A week was subsequently arranged for distribution of the questionnaires and of the information in each hospital by members of the research team. In delivering the questionnaires, informative talks were held, and explanatory posters were placed (defining the aim of the investigation and the procedure for supplying and collecting the questionnaires, and thanking all the professionals for their participation). The questionnaires were distributed by the investigators and liaison personnel selected in each center (supervisors, nurses and physicians). Boxes were made available for returning the completed questionnaires in places of easy access established by agreement with the personnel in each Unit.

Delivery of the questionnaires, including a prior informed consent document, was made once the purpose of the investigation had been explained, and after receiving approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos.

Maximum confidentiality and anonymity of each participant were guaranteed.

Qualitative variables were described as absolute and relative (percentage) frequencies, and associations were explored using the chi-squared test or the Fisher exact test. The confidence intervals of the study variables were calculated for an alpha error of 5%, using the SPSS version 18.0 statistical package.

ResultsA total of 649 questionnaires were distributed, of which 331 were collected again at the end of the reception period (three months)–the response rate therefore being 51% (Fig. 1).

With respect to the sociodemographic characteristics, 73.4% (n=243) of the professionals were women, 67.2% (n=222) were over 31 years of age, 20.5% (n=68) were physicians, and 79.5% (n=263) were nurses. In turn, 61.4% (n=203) of those surveyed had over 6 years of experience in the ICU. With regard to employment status, 46.8% (n=155) had fixed contracts, 20.8% (n=69) were interim personnel, and 32.3% (n=107) were eventual employees.

In relation to knowledge, 64.4% of the responders admitted not knowing the different documents referred to last wills–the precision being 3.9% according to the proportion observed.

With respect to the concrete measures contemplated in the AD, such as the limitation of therapeutic effort, palliative care, rejection of therapeutic insistence, and the designation of a legal representative, only 9.7% of the professionals claimed to be familiar with all of them.

The main variables related to knowledge of AD are described in Table 3.

Main results of the variables referred to knowledge, skills and attitudes.

| Qualitative variables | Items | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of the existing documents for expressing living wills | 118 (35.6) | |

| Living will is the same as advance directions | 60 (18.1) | |

| Advance directions registry is not mandatory in the Community of Madrid | 224 (67.7) | |

| Knowledge | Issuing advance directions in the presence of a notary public has the same validity as doing so in the presence of three witnesses | 167 (50.5) |

| Possibility of revocation of advance directions | 251 (75.85) | |

| There are limitations to the application of advance directions | 187 (56.5) | |

| Would respect the living will of a patient in the event of an extreme emergency | 232 (70.1) | |

| Skills | Awareness of the existence of a LW among the patients in his or her care | 19 (5.7) |

| Believes that the living will is respected | 154 (46.5) | |

| Attitudes | Believes that the living will is useful for the health professionals in the decision making process | 274 (82.8) |

With respect to skills, 90.6% (n=300) of the professionals did not check to see whether the patients in their care had a LW or not, and 50.2% (n=166) moreover indicated that the LW is not respected when required by the patient situation (e.g., the application of resuscitation maneuvers or the provision of a treatment which the patient had explicitly rejected in the directives).

The main results related to attitudes are described in Table 3.

More males than females claimed that they would respect a LW in the event of a life-threatening emergency (81.8% versus 65.8%; p=0.018), and were more aware of the existence or not of a LW among the patients in their care (11.4% versus 3.7%; p=0.012).

A total of 17.1% of the participants with over 16 years of experience in the ICU were familiar with all the measures contemplated by the AD, versus 1.4% of the professionals with under three years of experience (p=0.051) (Table 4). The differences observed with respect to professional category are reflected in Table 5.

Relationship between experience in the ICU and knowledge of the measures contemplated by the AD.

| Knows measures of AD | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Some | Don’t know/no answer | ||||

| Experience | (0–3 years) | Frequency | 1 | 56 | 15 | |

| Percentage | 1.4 | 77.8 | 20.8 | |||

| (3–5 years) | Frequency | 5 | 43 | 8 | ||

| Percentage | 8.9 | 76.8 | 14.3 | |||

| (6–10 years) | Frequency | 7 | 58 | 9 | 0.051 | |

| Percentage | 9.5 | 78.4 | 12.2 | |||

| (11–15 years) | Frequency | 5 | 30 | 12 | ||

| Percentage | 10.6 | 63.8 | 25.5 | |||

| >16 years | Frequency | 14 | 53 | 15 | ||

| Percentage | 17.1 | 64.6 | 18.3 | |||

Relationship between profession and the main variables referred to knowledge, skills and attitudes.

| Variables | Profession | Yes | No | Don’t know/no answer | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think LW is respected? | Physician | Frequency | 43 | 23 | 2 | 0.008 |

| Percentage | 63.2 | 33.8 | 2.9 | |||

| Nurse | Frequency | 111 | 143 | 9 | ||

| Percentage | 42.2 | 54.4 | 3.4 | |||

| Knows existing last will documents | Physician | Frequency | 42 | 26 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Percentage | 61.8 | 38.2 | 0 | |||

| Nurse | Frequency | 76 | 187 | 0 | ||

| Percentage | 28.9 | 71.1 | 0 | |||

| Would respect LW in extreme emergency | Physician | Frequency | 58 | 5 | 5 | 0.007 |

| Percentage | 85.3 | 7.4 | 7.4 | |||

| Nurse | Frequency | 174 | 58 | 31 | ||

| Percentage | 66.2 | 22.1 | 11.8 | |||

| Known if patients in his or her care have LW | Physician | Count | 13 | 54 | 1 | <0.001 |

| % of profession | 19.1 | 79.4 | 1.5 | |||

| Nurse | Count | 6 | 246 | 11 | ||

| % of profession | 2.3 | 93.5 | 4.2 | |||

With regard to the hospitals, the main characteristics are described in Table 6.

Relationship between hospitals and the main variables referred to knowledge, skills and attitudes.

| Hospitals | Do you think LW is respected? | Is LW a useful tool for health professionals? | Knows all measures of AD | Respect LW in extreme emergency | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know/no answer | p | Yes | No | Don’t know/no answer | p | All | Some | Don’t know/no answer | p | Yes | No | Don’t know/no answer | p | ||

| Hospital 1 | Frequency | 45 | 54 | 1 | 0.057 | 88 | 7 | 5 | 0.024 | 10 | 86 | 4 | 0.015 | 68 | 24 | 8 | 0.006 |

| Percentage | 45.0 | 54.0 | 1.0 | 88 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 86 | 4 | 68 | 24 | 8 | |||||

| Hospital 2 | Frequency | 31 | 35 | 3 | 54 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 43 | 19 | 53 | 7 | 9 | ||||

| Percentage | 44.9 | 50.7 | 4.3 | 78.3 | 5.8 | 15.9 | 10.1 | 62.3 | 27.5 | 76.8 | 10.1 | 13 | |||||

| Hospital 3 | Frequency | 5 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 4 | ||||

| Percentage | 41.7 | 58.3 | 0.0 | 58.3 | 16.7 | 25 | 0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 0 | 33.3 | |||||

| Hospital 4 | Frequency | 4 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Percentage | 28.6 | 64.3 | 7.1 | 71.4 | 0 | 28.6 | 14.3 | 57.1 | 28.6 | 57.1 | 14.3 | 28.6 | |||||

| Hospital 5 | Frequency | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Percentage | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 | 75 | 16.7 | 91.7 | 8.3 | 0 | |||||

| Hospital 6 | Frequency | 15 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 3 | ||||

| Percentage | 78.9 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 78.9 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 21.1 | 68.4 | 10.5 | 57.9 | 26.3 | 15.8 | |||||

| Hospital 7 | Frequency | 6 | 9 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Percentage | 40.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 | 73.3 | 20 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 0 | |||||

| Hospital 8 | Frequency | 17 | 25 | 1 | 34 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 7 | 25 | 15 | 3 | ||||

| Percentage | 39.5 | 58.1 | 2.3 | 79.1 | 16.3 | 4.7 | 9.3 | 74.4 | 16.3 | 58.1 | 34.9 | 7 | |||||

| Hospital 9 | Frequency | 23 | 19 | 5 | 39 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 30 | 14 | 37 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Percentage | 48.9 | 40.4 | 10.6 | 83 | 6.4 | 10.6 | 6.4 | 63.8 | 29.8 | 78.7 | 10.6 | 10.6 | |||||

On considering the work position, it must be mentioned that none of the residents in training were familiarized with all the measures contemplated by the AD, in comparison with 50% (n=4) of the non-healthcare nurses (supervisors) (p<0.001). On the other hand, 22% (n=11) of the staff physicians claimed to know whether the patients in their care had a LW, in contrast to 2.3% (n=6) of the healthcare nurses (p<0.001).

Regarding the type of working contract, 53.3% (n=57) of the eventual employees considered that LW are respected, while 57.4% (n=89) of the fixed employees consider that such wills are not respected (p=0.022).

Lastly, of the responders familiarized with all the measures contemplated by the AD, it must be noted that 100% (n=32) were of the opinion that such directives are useful for the professionals; 87.5% (n=28) pointed out that AD registry is not mandatory in the Community of Madrid; 71.9% (n=23) were aware of the possibilities of issuing such directives; 93.8% (n=30) pointed out the possibility of revocation; 56.3% (n=18) considered that such directives face some limitations in terms of application; 90.6% would respect a LW in the event of a life-threatening emergency; and only 12.5% (n=4) knew whether the patient had a LW or not (p<0.001).

DiscussionAs also pointed out by other authors,24 one of the best ways to respect patient autonomy in the ICU is to know the patient wishes and desires through the LW or AD.

A significant observation in our study was the fact that over one-half of all those surveyed claimed not to know the existing documents for expressing last wills. This is consistent with the observations of other studies25–31 that evidence insufficient and deficient knowledge on the part of the professionals and, consequently, on the part of the population. The study published by Lauzirika,26 involving primary care physicians, found that 83% of the health professionals did not have enough information or training to deal with the subject of AD in their patients. In our case, moreover, 90.3% of the responders were not familiarized with all the measures contemplated by the AD, and most of the professionals (90.6%) were not aware of whether the patients in their care had a LW or not. This directly interferes with the approach to last wills with both the patients and their families or legal representatives. We underscore the observation that of the total professionals who claimed to know all the measures contemplated by the AD and who moreover would respect such directives, only 12.5% were aware of whether their patients had a LW or not. This could indicate that this issue is in fact not addressed in routine practice, and is more a matter associated to theoretical knowledge. One of the possible reasons for this could also be difficulties among the professionals in accessing the AD electronic registry (ARETEO), since most intensive care professionals are not in possession of the required password.

However, in the abovementioned studies25–31 the professionals position themselves in favor of the usefulness of the LW in the decision making process, in coincidence with our own observations.

It seems clear that training measures are needed to improve and guarantee sufficient knowledge on AD, with acquisition of the corresponding skills and attitudes, with a view to optimizing professional competence in this field–especially considering that the professionals themselves recognize the usefulness of such directives.

In 2007, Mateos-Rodríguez et al.27 carried out a study on the attitudes of emergency care physicians and nurses in relation to AD. A full 73.5% claimed to know the term LW, though only 18% were familiar with current legislation on this matter. In our study the term LW was known to 69.8% of the responders, though many doubts were identified in relation to legislation, the issuing of directives and limitations. A total of 51% of the emergency care professionals claimed to have asked at some point before starting resuscitation maneuvers whether anyone knew the express wishes of the patient. In our case, 70.1% of the professionals affirmed that they would respect a LW in the event of an extreme emergency. Consequently, in this case there is agreement in the attitude of the professionals in both the ICU and in the emergency care setting.

Although our survey was limited to health professionals (physicians and nurses), mention should be made of a study25 published by Molina et al. in a hospital of the Community of Madrid. According to this study, 72.9% of the patients believed that having a LW would not change the attitude of the physician. This is in line with our own findings, since 50.2% of the professionals considered that the LW is not respected when the situation so requires, e.g., as when applying resuscitation maneuvers or administering treatments which the patient has previously rejected in his or her AD. This has important implications not only for the patient and family, but also for the professionals themselves.

With regard to the type of professional, in the year 2008 Simón-Lorda28 carried out two studies in two primary and specialized care areas–one in physicians and the other in nurses–in order to evaluate knowledge and attitudes referred to LW. In the case of the nurses, 63.1% were aware of the fact that such wills are regulated by law, though only 32.3% admitted to having read the document at some point. Most considered it convenient to plan and draft desires referred to medical care, and viewed the LW as a useful instrument for professionals. In our investigation, 64.6% of the nurses also knew that LW registry is not mandatory in the Community of Madrid; however, only 47.5% were aware of the legal possibilities of issuing the document. The majority were familiarized with the term LW, and also considered it to be useful in decision making–though only 66.2% would respect the LW in the event of a life-threatening emergency.

A paradox both in our study and in other publications27–31 is the fact that such directives are considered to be useful even though they are little known or respected. We deduce that this perceived usefulness is not associated to the experience of working with AD (since such directives are in fact little used); rather, it appears to be explained by the negative experiences (uncertainty, doubts, even errors) that sometimes arise in routine practice when the AD of critical patients are not known. Such negative experiences may also be taken to encompass inadequate resource utilization resulting from the futile prolongation of treatment measures.

Regarding the physicians who participated in the study of Simón-Lorda,29 the results were similar to those obtained among the nurses in the same investigation as regards the favorable opinion on the usefulness of LW, and the application and respect of such wills. The physicians also expressed willingness to complete a LW later on. In our case, the intensivists showed better knowledge of LW than the nurses; considered such wills more useful for the decision making process; and were more inclined to respect the LW in the event of an extreme emergency.

Nursing professionals need to receive precise information from the supervising physician, in order to avoid discrepancies or personal interpretations that might mask the reality of the patient.

Another study30 similar to that of Simón-Lorda and also carried out in primary and specialized care physicians and nurses in the Community of Madrid obtained similar results regarding the low level of knowledge and the favorable attitude regarding the application and usefulness of such directives.

In our study we consider it important to underscore that 17.1% of the participants with over 16 years of experience in the ICU knew all the measures contemplated by the AD, versus only 1.4% of the professionals with less than three years of experience. This is consistent with the study of Ameneiros et al.31 in primary and specialized care physicians, where greater knowledge was registered among the physicians with over 10 years of professional experience. Such experience is therefore a factor that favors knowledge of LW.

A study published by Solsona32 in 2007 pointed out that patients who are candidates for the drafting of a LW are those with chronic and evolving disease conditions, with a view to avoiding futile situations. However, mention must be made here of the two cases documented in the United States that greatly contributed to both the drafting of these documents and their legislation. These patients were Karen Ann Quinlan (1976) and Nancy Cruzan (1990), two young women suffering irreversible coma. Our proposal therefore is that LW should not be targeted only to terminal patients but also to all adults who because of unexpected circumstances might suffer a situation of disability in which they are unable to decide for themselves. This postulate is contemplated by current Spanish legislation referred to patient autonomy.

As a limitation of this study, it may be argued that the survey has been conducted in a single Spanish Autonomous Community–a fact that does not allow us to generalize the results to all the professionals (physicians and nurses) in the country. Nevertheless, the study does underscore a very important reality in the Community of Madrid, with a bearing also upon other Autonomous Communities.

In Spain, AD or LW documents are seen to be a largely unknown subject for both health professionals and patients. According to data from the Ministry of Health, up until March 2013, only 146,641 such directives had been recorded by the National Registry of Advance Directions (corresponding to 3.10 cases per 1000 inhabitants). Catalonia (6.14 cases) and the Basque Country (4.91 cases) were the Autonomous Communities with the highest rates, while Extremadura (0.96 cases per 1000 inhabitants), Ceuta and Melilla (0.01 cases) were the Communities with the lowest rates. With respect to the number of directives issued, Catalonia with 46,471 and Andalusia with 23,855 were the Communities with the largest number of registries.33,34 In January 2015, the data of the Spanish Ministry of Health reflected a small increase in the number of registered advance directions (180,327, corresponding to a rate of 3.85 cases per 1000 inhabitants). In the Community of Madrid the number has increased from 12,616 in 2013 to 16,363 in 2015.35

The present study has addressed this issue, exploring the professional competence of physicians and nurses in the ICU in dealing with these documents. This in itself has contributed to the diffusion of such documents, though much remains to be done. For example, limitation of life support protocols is needed in the Units, in order to ensure that all the professionals effectively speak the same language.

The health professionals recognize that although the LW is important for the decision making process, most of them do not know whether the patients in their care have such a will or not, and there is much uncertainty regarding its verification in the event of an extreme emergency. Indeed, some professionals, even knowing the existence of a LW, would not take it into account–with the possible ethical, social, familial, personal and economic consequences this may have. There is consequently much room for improvement in knowledge, skills and attitudes referred to AD, with a need for specific training, particularly among residents in intensive care and other specialties.

Not only the universities must work to ensure acquisition of the competences contemplated in their curricula. Training and compliance with AD also must be ensured from the professional organizations, including the respective general councils, and also from policy makers and the different Autonomous Communities.

The results obtained offer information that may serve to design training plans targeted to the professionals, as well as plans referred to patient care and information. This in turn will have a strong influence upon patient capacity to continue to exercise the right to personal autonomy, and will help improve the quality of health care.

Authors’ contributionAll the authors have participated in the conception of the study, as well as in the drafting, review and final approval of the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks are due to all the personnel of the intensive care units, since this study could not have been carried out without their participation. Thanks are also due to the supervisors of the Units of the nine hospitals forming part of the study, and particularly to Dr. Fernando Martinez-Sagasti and Ms. Pilar Bueno.

Please cite this article as: Velasco-Sanz TR, Rayón-Valpuesta E. Instrucciones previas en cuidados intensivos: competencias de los profesionales sanitarios. Med Intensiva. 2016;40:154–162.