Data on the epidemiology of infections caused by Clostridium difficile (CDI) in critically ill patients are scarce and center on studies with a limited time framework and/or epidemic outbreaks.

ObjectiveTo describe the characteristics and risk factors of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU with CDI, as well as the treatments used for the control of such infections.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was made of patients included in the ENVIN-ICU registry with CDI in 2012. Patients were followed up to 72h after discharge from the ICU. A case report form was used to record the following data: demographic variables, risk factors related to CDI, treatment and outcome. Infections were classified as community-acquired, nosocomial out-ICU and nosocomial in-ICU, according to the day on which Clostridium difficile isolates were obtained. Infection rates as episodes per 10,000 days of ICU stay are presented. The global in-ICU and hospital mortality rates were calculated.

ResultsSixty-eight episodes of CDI in 33 out of a total of 173 ICUs participating in the registry were recorded (19.1%) (2.1 episodes per 10,000 days of ICU stay). Forty-five patients were men (66.2%), with a mean (SD) age of 63.4 (16.4) years, a mean APACHE II score on ICU admission of 19.9 (7.4), and an underlying medical condition in 44 (64.7%). Sixty-two patients (91.2%) presented more than 3 liquid depositions/day, 40 (58.8%) in association with severe sepsis or septic shock. Community-acquired infection occurred in 13 patients (19.1%), nosocomial out-ICU infection in 13 (19.1%), and in-ICU infection in 42 (61.8%). Risk factors included age>64 years in 39 cases (57.4%), previous hospital admission (3 months) in 32 (45.6%), use of antimicrobials (previous 7 days) in 57 (83.8%), enteral nutrition in 23 (33.8%), and the use of H2 inhibitors in 39 (57.4%). Initial combined treatment was administered to 18 patients (26.5%). Metronidazole was used in 60 (88.2%) and vancomycin in 31 (45.6%). The in-ICU mortality rate was 25.0% (n=17), with a hospital mortality 27.9% (n=19).

ConclusionsThe rate of ICD in ICU patients is low, the infection affects severely ill patients, and is associated with high mortality. The presence of CDI is a marker of poor prognosis.

La epidemiología de las infecciones por Clostridium difficile (ICD) en pacientes críticos es escasa y centrada en estudios limitados en tiempo y/o en brotes epidémicos.

ObjetivoDescribir las características y los factores de riesgo de pacientes críticos ingresados en UCI con ICD, así como los tratamientos utilizados para su control.

Material y métodoAnálisis retrospectivo de pacientes incluidos en el registro ENVIN-UCI con ICD en el año 2012. Los pacientes se han seguido hasta 72h después de su alta de UCI. Se ha cumplimentado un cuaderno de recogida de datos, en el que se incluyen variables demográficas, factores de riesgo relacionados con Clostridium difficile, tratamiento y evolución. Los aislamientos se han clasificado por su origen en comunitarios, nosocomiales extra-UCI y nosocomiales intra-UCI en función del día de aislamiento. Se presentan las tasas por episodios por 10.000 días de estancia en UCI. Se describe la mortalidad global intra-UCI y hospitalaria.

ResultadosSe han detectado 68 episodios de ICD en 33 (19,1%) UCI de las 173 participantes en el registro (2,1 episodios por 10.000 días de estancia-UCI). En 45 (66,2%) casos eran hombres, con edad media de 63,4 (16,4) años, APACHE II al ingreso de 19,9 (7,4) y enfermedad de base médica 44 (64,7%). En 62 (91,2%) ocasiones presentaron más de 3 deposiciones líquidas/día y en 40 (58,8%) se asoció con sepsis severa o shock séptico. En 13 (19,1%) ocasiones fue de origen comunitario, en 13 (19,1%) de origen nosocomial extra-UCI y en 42 (61,8%) de origen intra-UCI. Factores de riesgo: edad>64 años 39 (57,4%), ingreso previo hospital (3 meses) 32 (45,6%), antimicrobianos (7 días previos) 57 (83,8%), nutrición enteral 23 (33,8%) e inhibidores H2 39 (57,4%). Siguieron tratamiento inicial combinado 18 (26,5%) casos y se ha utilizado metronidazol en 60 (88,2%) y vancomicina en 31 (45,6%) casos. Hubo mortalidad global intra-UCI en 17 (25,0%) casos y hospitalaria de 19 (27,9%).

ConclusionesLa tasa de ICD en pacientes ingresados en UCI es baja y afecta a pacientes con elevada gravedad y mortalidad. La presencia de ICD es un marcador de mal pronóstico.

Infections caused by Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) (CDI) are generally diagnosed by the presence of persistent liquid diarrhea, with the identification of C. difficile in a stool sample using some of the different tests available. A diagnosis based on colonoscopic or histopathological findings evidencing the presence of pseudomembranous colitis is less common.1 The importance of such infections is reflected by the fact that C. difficile may be present in 20–30% of the cases of diarrhea associated to antimicrobial use.2 Few epidemiological data are available on the prevalence of CDI in hospitalized patients, and there is even less information referred to critical patients admitted to Departments of Intensive Care Medicine or Intensive Care Units (ICUs). A study made between 1997 and 2005 in Canadian hospitals recorded an incidence of between 3.4 and 8.4 cases per 1000 admissions in acute care hospitals, and of 3.8–9.5 cases per 10,000 patients-day.3,4 The mortality rate attributed to CDI is low (less than 2%),4,5 though the associated excess costs in American hospitals during the period 2000–2002 was estimated to be 3200million USD/year.6

The risk factors underlying CDI include old age (>64 years),7,8 the duration of hospital stay,9 exposure to antimicrobial drugs,10 cancer chemotherapy,11,12 immune depression related to HIV infection,13 gastrointestinal surgery,14 enteral diet administered through a nasogastric tube,15 and the administration of acid-suppressing drugs (antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors).16 Many of these factors are present in critical patients admitted to the ICU. However, infection registries in such Units tend to focus on infections related to the use of invasive devices17–the information on CDI being scarce and limited to the description of epidemic outbreaks and mortality or cost increment estimates.18–23 The objective of this study is to determine the characteristics of critical patients with CDI admitted to Spanish ICUs in the year 2012, independently of the origin of the infection, and to describe the factors related to the development of CDI and the treatment strategies employed.

MethodologyDesignA retrospective, non-interventional, multicenter observational study was carried out with the voluntary participation of ICUs that routinely collaborate in the ENVIN-ICU registry. Since the year 1994, this registry monitors the evolution of infections related to invasive devices, their etiology, resistance markers, and the antimicrobials used in Spanish ICUs (accessible at: http://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics/).

Case definitionA case is defined as any patient admitted to an ICU or critical care unit and in which the presence of C. difficile is identified.

Study periodWe included all patients with positive C. difficile isolates admitted to the ICUs participating in the abovementioned registry in the year 2012. The patients were followed-up on throughout their stay in the ICU and during the 72h after discharge from the Unit.

Clostridium difficile detection techniquesThe identification of C. difficile was based on the routine techniques used in the Microbiology laboratory of each of the participating hospitals, and which comprised one or more of the following: stool culture, determination of the enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), enzymoimmunoassay for toxins A and B, studies of cell cytotoxins and toxigenic cultures, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques.

Data collectionA case report form (CRF) was used to record demographic data, hospital and ICU admission and discharge dates, diagnosis upon admission, severity as assessed by the APACHE II scale,24 and the need for emergency surgery during admission. The patients were classified according to the diagnosis upon admission as coronary, surgical, trauma or clinical cases.17 Coronary patients were those admitted due to acute or chronic coronary syndrome with or without ST-segment elevation. Trauma patients in turn were those admitted due to acute injuries, while surgical patients were defined as individuals admitted for postoperative control of scheduled surgery. Lastly, clinical patients were those admitted due to reasons unrelated to the above, including individuals admitted after non-scheduled surgery.

We likewise documented the comorbidities, invasive devices, techniques and treatments used on the day of the isolation of C. difficile, and the previously administered antibiotics and their duration. The comorbidities evaluated were immune depression, immune suppression, neutropenia and solid organ transplantation. Instrumentations and controlled techniques comprised mechanical ventilation, bladder catheterization, central venous catheter placement, extrarenal filtration techniques, ventricular shunt catheters, parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition and previous surgery. The following definitions were used17: immune suppression when the patient received treatment lowering resistance to infection (chemotherapy, radiation, prolonged or high-dose corticosteroids) or suffered disease in a sufficiently advanced stage to suppress the host defenses against infection; neutropenia in the presence of a neutrophil count of <500cells/mm3; and immune depression when the patient had been diagnosed with HIV infection or some other congenital or acquired immune deficiency.

In etiological terms, CDI was classified as community-acquired when the patient presented liquid diarrhea and positive identification of C. difficile at the time of admission or in the first 48h after admission to hospital; nosocomial out-ICU when the clinical manifestations and diagnosis were registered after the first 48h in hospital and in the first 48h of admission to the ICU; and nosocomial in-ICU when the diagnosis was established after the first 48h in the ICU or in the first 72h after discharge from the Unit.

The specific risk factors for CDI considered in the study were: age>64 years, previous antimicrobial use for over 7 days, other hospital admissions in the previous three months, a history of HIV disease, gastroduodenal surgery, chemotherapy use in the previous three months, and the current use of enteral nutrition and/or H2 inhibitors.

The systemic response to infection was recorded, defined as the presence of sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock not attributable to other infectious causes. The specific treatment administered for CDI was classified as monotherapy when the patient received a single antibiotic for the infection (independently of whether other antibiotics were also used to treat other infections), and dual therapy when two antibiotics were administered simultaneously. The clinical response in turn was classified as cure, improvement, without changes, and death related to the infection, while microbiological response was classified as the negative conversion of cultures, persistence, appearance of another microorganism in stools, and no follow-up. The patients were followed-up until discharge from hospital in order to identify possible reinfections. The classification of reinfection required cure or improvement of a previous episode and/or a negative stool test. Lastly, overall mortality was defined as death occurring during admission to the ICU or in the hospital, due to any cause.

Calculation of ratesThe frequency of CDI was defined by the number of episodes recorded in patients admitted to the ICU (regardless of the origin of the infection) per 1000 patients admitted to the ICU and per 10,000 days of stay in the ICU. In calculating the rates we considered only those patients included in the ENVIN-ICU registry during the national vigilance period (April–June), since the data referred to the number of patients and days of stay in the ICU at Spanish national level are available for these months (19,521 patients and 150,832 days of stay in the ICU).

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables are described with the percentage distribution of each of the categories, while the quantitative variables are described using the mean and standard deviation in the case of a normal distribution, and the median and range in the case of a non-normal distribution.

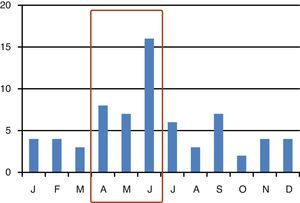

ResultsThe study included 68 patients with CDI in 33 (19.1%) ICUs of the 173 Units were participating in the ENVIN-ICU registry (2.1 patients per ICU with CDI; range 1–6). The distribution of cases over the months is shown in Fig. 1. The CDI episode rates referred to the national participation period in the registry (April–June) were 1.59 per 1000 patients admitted to the ICU, and 2.06 episodes per 10,000 days of stay in the ICU (patients-day). Forty-five patients were males (66.2%), with a mean age of 63.4 (16.4) years, an APACHE II score upon admission of 19.9 (7.4), and a predominantly clinical background disease condition in 44 cases (64.7%) (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) admitted to the Intensive Care Units.

| Characteristics of the patients | n=68 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) (range) | 63.4 (16.4) (24–87) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 45 (66.2) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) (range) | 19.9 (7.4) (2–36) |

| Type of patient, n (%) | |

| Clinical | 44 (64.7) |

| Surgical | 22 (32.4) |

| Trauma | 2 (2.9) |

| Emergency surgery, n (%) | 20 (29.4) |

| Patient origin, n (%) | |

| Home | 30 (44.1) |

| Hospitalization unit | 34 (50.0) |

| Other healthcare center | 4 (5.9) |

| Days of stay in hospital, mean (SD) (range) | 40.2 (38.0) (3–179) |

| Days of stay in ICU, mean (SD) (range) | 17.4 (19.9) (1–73) |

| Days of stay in hospital-isolation CD, mean (range) | 14.1 (19.9) (0–77) |

| Days of stay in ICU-isolation CD, mean (range) | 6.5 (13.3) (0–52) |

| Overall in-ICU mortality, n (%) | 17 (25.0) |

| Overall hospital mortality, n (%) | 19 (27.9) |

CD, Clostridium difficile; SD, standard deviation.

In 62 cases (91.2%), CDI was associated to clinical manifestations in the form of liquid depositions, and in 40 cases (58.8%) a systemic inflammatory response was present in the form of severe sepsis or septic shock. In one case CDI evolved toward toxic megacolon requiring emergency surgery for control and treatment. In 13 cases (19.1%), CDI was classified as being community acquired, while another 13 (19.1%) were of nosocomial out-ICU origin, and 42 (61.8%) were nosocomial in-ICU infections (Table 2).

Characteristics of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and diagnostic methods.

| Characteristics of CDI | n=68 |

| Form of presentation, n (%) | |

| Liquid depositions | 62 (91.1) |

| Three or more depositions/day | 53 (77.9) |

| Systemic inflammatory response, n (%) | |

| Severe sepsis or septic shock | 40 (58.8) |

| Origin of CDI, n (%) | |

| Community-acquired | 13 (19.1) |

| Nosocomial in-hospital (out-ICU) | 13 (19.1) |

| Nosocomial in-ICU | 42 (61.8) |

| Study method, n (%) | |

| Stool culture | 25 (36.8) |

| Enzyme studies (GDH) | 36 (52.9) |

| Toxin detection tests (EIA) | 17 (25.0) |

| PCR | 6 (8.8) |

| Number of tests per sample, n (%) | |

| 1 | 50 (73.5) |

| 2 | 10 (14.7) |

| 3 | 4 (5.9) |

| Not known | 4 (5.9) |

EIA, enzymoimmunoassay; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ICU, Intensive Care Unit.

Table 3 shows the comorbidities and invasive devices in the patients with CDI. Of note is the great need for monitoring techniques (Table 4). The specific factors related to CDI were a patient age of >64 years in 39 subjects (57.4%), admission to hospital in the preceding three months in 31 (45.6%), the use of antimicrobials in the 7 days before the diagnosis of CDI in 57 (83.8%), the use of enteral nutrition in 23 (33.8%), and the prescription of H2 inhibitors in 39 patients (57.4%). In contrast, chemotherapy (7 patients, 10.3%) and gastroduodenal surgery (5 patients, 7.4%) were much less frequent. Forty-four patients with CDI (64.8%) presented three or more specific risk factors for this infection. Among the groups of antimicrobials used before the diagnosis of CDI, mention must be made of betalactams associated to betalactamase inhibitors (36.8%), carbapenems (33.8%) and cephalosporin (23.5%).

Disease antecedents, invasive devices and complementary treatments of patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) admitted to the Intensive Care Units.

| n=68 | |

| Disease antecedents, n (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (25.0) |

| COPD | 12 (17.6) |

| Solid organ neoplasm | 8 (11.8) |

| Hematological malignancy | 8 (11.8) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 5 (7.4) |

| Chronic renal failure | 13 (19.1) |

| Solid organ transplant | 4 (5.9) |

| Bone marrow transplant | 1 (1.5) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (3.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 9 (13.2) |

| Neutropenia | 4 (5.9) |

| Immune depression | 12 (17.6) |

| Invasive devices, n (%) | |

| Central venous catheter | 54 (79.4) |

| Arterial catheter | 34 (50.0) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 29 (42.6) |

| Bladder catheter | 56 (82.4) |

| Parenteral nutrition | 23 (33.8) |

| Extrarenal filtration | 7 (10.3) |

| Antimicrobial use>7 days | 46 (67.6) |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 22 (32.4) |

| Surgery during admission, n (%) | 17 (25.0) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Risk factors related to Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in patients admitted to the Intensive Care Units.

| Specific risk factors for CDI, n (%) | n=68 |

| Age>64 years | 39 (57.4) |

| Hospital admission in the previous 3 months | 31 (45.6) |

| Use of ATB in the previous 7 days | 57 (83.8) |

| Chemotherapy | 7 (10.3) |

| HIV infection | 1 (1.5) |

| Gastroduodenal surgery, n (%) | 5 (7.4) |

| Enteral nutrition, n (%) | 23 (33.8) |

| Use of H2inhibitors | 39 (57.4) |

| Number of specific factors per CDI patient | |

| 0 | 3 (4.4) |

| 1–2 | 21 (30.9) |

| 3–4 | 39 (57.4) |

| >4 | 5 (7.4) |

ATB, antibiotics; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Specific treatment for CDI was indicated in 66 patients (97.1%) (Table 5) in the form of a single antibiotic in 42 cases (61.8%) and two or more in 24 (35.3%)–though in only 18 cases were both drugs administered simultaneously. Metronidazole predominated, with 60 (88.2%) cases, followed by vancomycin in 31 (45.6%). The use of these antibiotics, specifically prescribed for the treatment of CDI, was accompanied by the use of other antimicrobials for the treatment of other infections in 24 cases (35.3%). Seven patients (10.3%) presented adverse effects probably or possibly related to the administration of antimicrobials specific for CDI, including hematological disorders (2 cases) and water–electrolyte alterations (2 cases) in relation to the administration of metronidazole, and a case of severely altered liver function associated to the simultaneous use of metronidazole and vancomycin. In one case the initial treatment was changed because of the adverse effects.

Specific treatment for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in patients admitted to the Intensive Care Units.

| Specific treatment for CDI | n=68 |

| Patients with previous ATP, n (%) | 57 (83.8) |

| Patients with ATB, according to administered number, n (%) | |

| None/not specified | 8 (11.8) |

| 1 | 17 (25.0) |

| 2 | 16 (23.5) |

| 3 or more | 27 (39.7) |

| Previously administered ATB, n | 130 |

| Semisynthetic penicillins, n (%) | 7 (10.3) |

| Betalactams plus betalactamase inhibitors, n (%) | 25 (36.8) |

| Cephalosporins, n (%) | 16 (23.5) |

| First generation | 2 (2.9) |

| Second generation | 2 (2.9) |

| Third generation | 9 (13.2) |

| Fourth generation | 3 (4.4) |

| Carbapenems, n (%) | 23 (33.8) |

| Aminoglycosides, n (%) | 6 (8.8) |

| Quinolones, n (%) | 10 (14.7) |

| Clindamycin, n (%) | 1 (1.5) |

| Glycopeptides, n (%) | 6 (8.8) |

| Cotrimoxazole, n (%) | 1 (1.5) |

| Linezolid, n (%) | 11 (16.2) |

| Antimicrobials specific for CDI, n (%) | |

| Metronidazole | 60 (88.2) |

| Vancomycin | 31 (45.6) |

| Vancomycin and metronidazole | 18 (26.5) |

| Antimicrobials simultaneous to those administered for CDI, n (%) | 24 (35.3) |

| Patients with adverse effects related to specific ATB, n (%) | 7 (10.3) |

| Water-electrolyte alterations (hypopotassemia, hypomagnesemia) | 2 |

| Hematological alterations | 2 |

| Liver function alterations | 1 |

| Others | 3 |

ATB, antibiotics; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection.

The clinical response was considered satisfactory (cure and/or improvement) in 51 cases (75.0%), while no changes or failures were recorded in 10 (14.7%). The response was not evaluable in another four cases (5.9%). Negative microbiological conversion was achieved in 37 cases (61.7%), follow-up was not conducted in 20 (29.4%), and persistence was detected in two subjects (2.9%). In the patients treated with metronidazole in monotherapy (n=36), the satisfactory response rate was 77.8%, versus 100% with vancomycin (n=7), and 61.1% with both antibiotics (n=18). Only two cases of reinfection were recorded. The overall in-ICU mortality rate was 25.0% (n=17), while another two patients died in hospital after discharge from the ICU (overall in-hospital mortality rate 27.9%; n=19). In no case could mortality be related to CDI (Tables 5 and 6).

Clinical and microbiological response to specific treatment for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in patients admitted to the Intensive Care Units.

| n=68 | |

| Clinical response, n (%) | |

| Cure | 44 (64.7) |

| Improvement | 7 (10.3) |

| Without changes (failure) | 10 (14.7) |

| Not evaluable | 4 (5.9) |

| Microbiological response, n (%) | |

| Negative conversion | 37 (61.7) |

| Persistence | 2 (2.9) |

| Appearance of other microorganisms | 1 (1.5) |

| No follow-up | 20 (29.4) |

| Reinfection | 2 (2.9) |

The main contribution of this study has been the description of the critical patients admitted to Spanish ICUs with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). These patients are generally elderly, with background clinical disease and multiple comorbidities, a high degree of severity upon admission to the ICU, the need for broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, and with abundant liquid depositions in the first week of stay in the ICU. In 62% of the cases the ICU was found to be the origin of CDI.

The estimated CDI rates in the months of April to June were 1.6 cases per 1000 patients admitted to the ICU and 2.1 episodes per 10,000 stays in ICU (patients-day). Most studies in patients admitted to the ICU refer to epidemic outbreaks or endemic situations in one or more centers, or conduct an analysis of the impact of CDI upon stay, costs and mortality in an ICU characterized by a high proportion of patients with this infection. Recently, Bouza et al.,18 on occasion of the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (April 2013, Berlin, Germany), reported the CDI rate corresponding to the last 10 years in the four ICUs of a general hospital. The global incidence of CDI was 13.2 cases per 10,000 days of stay in the ICU, and the figure showed a clear tendency to decrease in recent years (from 15.9 in 2003 to 8.8 in 2012). Likewise, the authors demonstrated the existence of important differences in rates depending on the characteristics of the ICU–the highest rates being found in clinical ICUs attending patients following heart surgery. Zahar et al.19 in turn published a retrospective study on the clinical impact of CDI in patients admitted to three ICUs. The rates recorded in their study were 13.1 cases per 1000 patients (calculated figure) and 3.6 cases of CDI acquired in the ICU per 1000 patients-day. Lawrence et al.22 conducted a retrospective analysis of the impact of C. difficile colonization as a risk factor for the development of CDI. They documented a rate of 35.3 new cases per 1000 patients admitted for over 24h to the ICU (calculated figure). In both of the aforementioned studies the rates were higher than those recorded in our registry. This may be because we included ICUs with very distinct characteristics and risks, and without endemic conditions for this particular pathogen. In fact, only one out of every 5 ICUs (19%) that contributed data to the registry identified cases of CDI.

A possible reason for the reduced diagnosis of CDI in our setting may be the lack of a pre-established study method. A study conducted in a Spanish hospital has demonstrated that the application of a control and vigilance program doubles the recorded CDI rate.25 In this sense, homogenization of the study methodology in cases of suspected CDI has been advocated at European and American level, proposing a search for the infection in all patients admitted to the ICU with liquid diarrhea, defined as three of more liquid depositions in the course of 24 consecutive hours (or less).26,27 The watery, liquid or unformed stool samples should be quickly sent to the Microbiology laboratory for routine study, including the investigation of C. difficile.

In our study, the tests used for the diagnosis of CDI have been those routinely employed in each Microbiology laboratory, with a predominance of stool cultures, the determination glutamate dehydrogenase, enzymoimmunoassay for toxins A and B, and, in fewer cases, polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In order to homogenize the identification of CDI, a diagnostic protocol (2-step algorithm) has been proposed, with due adaptation to the possibilities of each individual laboratory.26,27 A first determination is made of glutamate dehydrogenase, followed in positive cases by enzymoimmunoassay for toxins A and B. Only when these two techniques prove negative is a more specific third technique suggested (PCR or toxigenic cultures). As a less expensive alternative, this step can be replaced by stool culture, followed in positive cases by direct toxin determination in the isolates.

The treatment used mainly consisted of monotherapy with metronidazole and, in fewer cases, with vancomycin. The preferential choice of metronidazole evidences that the form of presentation of CDI is regarded by the clinicians as mild or moderate, since in the more severe or complicated presentations oral (or rectal, in the case of paralytic ileus) vancomycin is recommended, with or without metronidazole simultaneously.1 A recent review28 has analyzed the studies that established comparative assessments of the efficacy of the different antimicrobials used to treat CDI. All of them were of low to moderate statistical power, and no differences were observed among the treatments. It should be mentioned that up to one-quarter of all the therapies used in our series were administered as the combination of both antibiotics, despite a lack of evidence warranting their effectiveness. In 7 of the cases (10%), adverse reactions attributed to the antibiotics used to treat CDI were recorded.

The clinical response to the treatment provided was rated as satisfactory (cure or improvement) in 75% of the cases. In the rest of the cases evaluation was not possible or no changes were observed in patients who died as a result of progression of their background disease condition. The overall in-ICU mortality rate was 25%, and in no cases could death be related to CDI. Different studies have examined the impact of the presence of CDI upon mortality among critical patients. Most of them show the presence of CDI to be associated to high overall in-ICU and in-hospital mortality19–22,29; however, on conducting comparative analyses (involving patients with diarrhea without CDI or case-controls), no relationship was observed between the presence of CDI and patient mortality.19,29

The reported frequency of CDI recurrence is between 6 and 25%.1 The recurrence rate in our study was low. This may be because a quarter of the patients have died, and follow-up was only made until discharge from hospital.

This study has important limitations, such as its retrospective nature based on the analysis of reported cases in the context of a voluntary national registry. The registry of CDI was first included in the year 2012, and this may have caused omissions in recording the infection. On the other hand, no common protocol was used to request microbiological studies in patients at risk, and the tests applied to the stool samples varied from one hospital to another. Likewise, we have not been able to establish a relationship between the presence of CDI and outcome.

In sum, the present study contributes information on the characteristics of the patients with CDI admitted to Spanish ICUs, and on the treatments provided. Of note in this respect is the fact that two antibiotics were administered simultaneously in one-quarter of the cases. The calculated infection rates were lower than those published by other authors and fell short of the rates expected from the CDI-specific risk factors present in these patients–thus evidencing that C. difficile infection is underdiagnosed in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU. A consensus-based study methodology is needed (collection and submission of samples and specific tests in the Microbiology laboratories) in reference to patients with liquid depositions in our setting.

Financial supportM. Palomar has received an international grant from Pfizer for maintenance of the ENVIN-ICU registry. F. Alvarez-Lerma has received a grant from Astella-Farma for the collection and analysis of the data referred to Clostridium difficile infection.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The ENVIN-ICU registry is promoted by the Infectious diseases Work Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care and Coronary Units (GTEI-SEMICYUC), and has been maintained in the year 2012 thanks to an international grant from Pfizer S.A. The list of participating centers and the collaborators in the registry are contained in the report corresponding to the year 2012, which can be freely accessed at: http://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics/. The analysis of the cases of C. difficile has been carried out in part with the support of Astella-Farma. The authors thank Sergio Mojal, of the Instituto Municipal de Investigación of Hospital del Mar, for methodological counseling and statistical analysis.

List of supervising physicians in the ICUs who have completed the case report forms of patients with CDI: A. Bonet, L. Saló (Clínica Girona); G. Aguilar, C. García Márquez (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia); M.L. Mora, M. Lequona (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias); A. Díaz, L. Pita, R. Arrojo (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña); J.C. Montejo, M. Catalán (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid); M.J. Castro, F.J. Rodríguez (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, Ferrol, A Coruña); F. Esteve (Hospital de Bellvitge, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona); D. Fontaneda Lopez, S. Gutierrez (Hospital de León); E. Antón (Hospital de Manacor); I. Catalán (Hospital de Manresa Altaya, Barcelona); J. Almirall, M. de la Torre (Hospital de Mataró, Barcelona); J.L. Antón, C. Dolera (Hospital de Sant Joan, Alacant); M.B. López, M.B. Estévanez (Hospital del Tajo, Aranjuez, Madrid); J. Amador, M.T. Jurado (Hospital de Terrassa, Barcelona); A. Villasboas, A. Rey (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); R. Reig (Hospital General de Castellón); A.M. Rodríguez, M. Sánchez Palacios (Hospital Insular de las Palmas, Canarias); B. Gil, N. Llamas (Hospital Morales Massaguer, Murcia); J.A. Cambronero, M. Daguerre (Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); A. Blanco (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo); J.R. Iruretagoyena, M. Domezaín (Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Vizcaya); A. Abella, F. Gordo (Hospital Universitario de Henares, Madrid); P. Albert de la Cruz, E. García (Hospital Universitario del Sureste, Arganda del Rey, Madrid); S. Alcántara, I. Fernández Simón (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, Majadahonda, Madrid); A.J. Pontes, J.C. Pozo (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba); Á. López, C. Susarte (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia); M. Palomar, C. Laborda (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona); A. Martinez Pellús, E. Andreu (Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia); M.P. Posada (Hospital Xeral de Vigo); R. Ferrer (Mútua de Terrassa, Barcelona); J.M. Quiroga, M. Sadaba (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón); A.M. Mendía Gorostidi (Hospital de Donostia Ntra. Sra. de Aranzazu, San Sebastián); A. Rovira (Hospital General de Hospitalet, Barcelona); H. Abdel-Hadi (Hospital General, Ciudad Real).

The investigators that have contributed cases to this study are cited in Annex.

Please cite this article as: Alvarez-Lerma F, Palomar M, Villasboa A, Amador J, Almirall J, Posada MP, et al. Estudio epidemiológico de infección por Clostridium difficile en pacientes críticos ingresados en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos. Med Intensiva. 2014;38:558–566.