An analysis is made of the clinical profile, evolution and differences in morbidity and mortality of low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS) in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery, according to the three diagnostic subgroups defined by the SEMICYUC Consensus 2012.

DesignA multicenter, prospective cohort study was carried out.

SettingIntensive Care Units of Spanish hospitals with cardiac surgery.

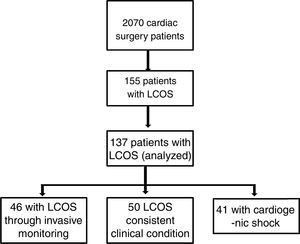

PatientsA consecutive sample of 2070 cardiac surgery patients was included, with the analysis of 137 patients presenting LCOS.

InterventionsNo.

ResultsThe mean patient age was 68.3±9.3 years (65.2% males), with a EuroSCORE II of 9.99±13. NYHA functional class III and IV (52.9%), left ventricular ejection fraction <35% (33.6%), acute myocardial infarction (31.9%), severe pulmonary hypertension (21.7%), critical preoperative condition (18.8%), prior cardiac surgery (18.1%), PTCA/stent placement (16.7%). According to subgroups, 46 patients fulfilled hemodynamic criteria of LCOS (group A), 50 clinical criteria of LCOS (group B), and the rest (n=41) presented cardiogenic shock (group C). Significant differences were observed over the evolutive course between the subgroups in terms of time subjected to mechanical ventilation (114.4, 135.4 and 180.3min in groups A, B and C, respectively; p<0.001), renal replacement requirements (11.4%, 14.6% and 36.6%; p=0.007), multiorgan failure (16.7%, 13% and 47.5%), and mortality (13.6%, 12.5% and 35.9%; p=0.01). The mean maximum lactate concentration was higher in cardiogenic shock patients (p=0.002).

ConclusionsThe clinical evolution of these patients leads to high morbidity and mortality. Differences were found between the subgroups in terms of postoperative clinical course and mortality.

Análisis del perfil clínico, la evolución y las diferencias en morbimortalidad en el síndrome de bajo gasto cardiaco (SBGC) en el postoperatorio de cirugía cardiaca, según los 3 subgrupos de diagnóstico definidos en el Consenso SEMICYUC 2012.

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes prospectivo multicéntrico.

ÁmbitoUCI de hospitales españoles con cirugía cardiaca.

PacientesMuestra consecutiva de 2.070 pacientes intervenidos de cirugía cardiaca. Análisis de 137 pacientes con SBGC.

IntervencionesNo se realiza intervención.

ResultadosEdad 68,3±9,3 años, 65,2% varones, con un EuroSCORE II de 9,99±13. Los antecedentes a destacar fueron: NYHA III-IV (52,9%), FEVI<35% (33,6%), IAM (31,9%), HTP severa (21,7%), estado crítico preoperatorio (18,8%), cirugía cardiaca previa (18,1%) y ACTP/stent (16,7%). Según subgrupos, 46 pacientes cumplían criterios hemodinámicos de SBGC (grupo A), 50 criterios clínicos (grupo B) y el resto (n=41) fueron shock cardiogénico (grupo C). En la evolución, se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los subgrupos en el tiempo de ventilación mecánica (114,4, 135,4 y 180,3min, para A, B y C, respectivamente, p<0,001), la necesidad de reemplazo renal (11,4, 14,6 y 36,6%, p=0,007), el fracaso multiorgánico (16,7, 13 y 47,5%) y la mortalidad (13,6, 12,5 y 35,9%, p=0,01). La media de lactato máximo fue mayor en los pacientes con shock cardiogénico (p=0,002).

ConclusionesLa evolución clínica de estos pacientes con SBGC conlleva una elevada morbimortalidad. Encontramos diferencias entre los subgrupos en el curso clínico postoperatorio y la mortalidad.

Low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS) is a potential complication in patients that have undergone cardiac surgery (CS). According to the studies found in the literature, the incidence of the syndrome varies between 3 and 45%, and it is associated to increased morbidity–mortality, a prolongation of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), and increased consumption of resources.1–4 Low cardiac output syndrome can be regarded as a “peculiar” form of acute heart failure (AHF), characterized by triggering factors, a form of presentation, evolution and treatment that differ from those of AHF of medical origin. The AHF classifications of the European Society of Cardiology and of the American College of Cardiology are not directly applicable to the postoperative period of CS; in fact, they do not contemplate the mentioned syndrome.5 Postoperative LCOS involves the association of cardiogenic, distributive and hypovolemic components that affect patient hemodynamics and imply complex management requiring a dynamic clinical approach. In this context, in the year 2012 a consensus document was published specifically defining this clinical condition and offering a series of global recommendations for its treatment.6

The present study investigates the possible pre- and intraoperative factors associated to LCOS and which can influence its outcome. The complex postoperative course of these patients is examined, and a study is made of the differences among the different clinical diagnostic subgroups (referred to both the association of predisposing factors and evolution and prognosis).

Patients and methodsA prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study was made of a group of patients with LCOS in the postoperative period of CS (the ESBAGA Study), with the purpose of evaluating the postoperative course and prognosis (clinical evolution, presence of complications and mortality) of the patients, and the differences according to the three different LCOS diagnostic subgroups defined by the SEMICYUC Consensus 2012. The pre- and intraoperative factors associated to development of the syndrome were also analyzed.

Study populationThe study was carried out in 14 Intensive Care Units (ICUs) belonging to hospitals throughout Spain, and involved patients admitted to the ICU during the early postoperative period of CS, with a diagnosis of LCOS.

Inclusion criteria: patients with LCOS as defined by the “Clinical practice guides for the management of low cardiac output syndrome in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery” of the SEMICYUC6:

- -

Postsurgery LCOS: Monitored cardiac index <2.2l/min/m2, without associated relative hypovolemia, secondary to left and/or right ventricular failure, and associated or not to pulmonary and/or systemic congestion.

- -

LCOS consistent clinical condition: This corresponds to patients not monitored and where the cardiac index is not known, though the clinical manifestations are consistent with low cardiac output: oliguria (diuresis <0.5ml/kg/h), central venous oxygen saturation <60% (with normal arterial oxygen saturation) and/or lactate >3mmol/l, without relative hypovolemia.

- -

Cardiogenic shock (CaS): This is the most serious scenario in LCOS, and is defined as cardiac index <2.0l/min/m2, with systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, without relative hypovolemia and with oliguria.

The inclusion period was from June 2014 to June 2015. The intensivist selected the patients as they were subjected to surgery, after confirming compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and using the consecutive sampling technique.

This was a non-interventional study requiring no complementary laboratory or diagnostic tests other than those contemplated per protocol in each center.

Approval of the study was obtained from the Clinical Ethics Research Committee of each participating center. All the patients (or their representatives) signed the consent form for inclusion in the study.

The main study variables were:

- -

Demographic and general information: Gender, age, type of intervention, comorbidities and surgical procedure.

- -

Presurgical variables: Previous surgery, functional class (NYHA), history of cardiovascular risk and EuroSCORE II data, previous coronary angioplasty (PTCA)/stent placement, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), preoperative critical condition as defined by the EuroSCORE II (fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia or resuscitated sudden cardiac death, perioperative cardiac massage, previous mechanical ventilation, inotropic drugs, preoperative balloon counterpulsation technique, anuria or oliguria <10ml/h).

- -

Intraoperative variables: Characteristics of surgery, aortic clamping time, extracorporeal circuit (ECC) time, difficulty suspending ECC (defined by the need for more than two vasoactive drugs on emerging from ECC, or the need for pump reentry).

- -

Postoperative variables: Mechanical ventilation time to extubation, use of inotropic/vasoactive drugs, presence of cardiac and surgical complications (repeat surgery due to bleeding or tamponade, acute lung edema, perioperative acute myocardial infarction [AMI], maximum ultrasensitive troponin T levels, arrhythmias), renal complications (acute renal dysfunction, need for renal replacement therapy), neurological, respiratory, infectious and gastrointestinal complications, laboratory test results (maximum lactate, alanine aminotransferase), multiorgan failure (MOF).

- -

Global evolutive parameters: Stay in ICU and outcome (alive/deceased).

The tables and figures were generated from the number of valid cases (n), and this was the number considered for the calculation of percentages or other statistical applications. Continuous variables were reported as the number of valid cases, the mean and standard deviation, and the maximum and minimum values, while categorical variables were reported as the number of valid cases and the percentage of each category.

Continuous variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation, or as the median and interquartile range (IQR), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparison purposes, depending on the nature of the variables (as established by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Categorical variables were reported as absolute values and percentages, and the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test was used for comparisons between groups, as applicable. The SPSS version 19.0 statistical package for MS Windows was used throughout. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 14 Intensive Care Units belonging to hospitals throughout Spain participated in the ESBAGA study (Table 1). We analyzed a total of 2070 patients subjected to CS, of which 155 presented LCOS in the immediate postoperative period (7.5%). Eighteen of these subjects declined participation in the study; 137 patients were therefore finally evaluated. Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of these patients.

Participating centers.

| Participating centers: 14 | Patients: 137 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias | 21 (15.2) |

| Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid | 19 (14.3) |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid | 19 (14.3) |

| Hospital Universitario Doce de Octubre, Madrid | 15 (10.9) |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla | 12 (8.7) |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona | 12 (8.7) |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | 9 (6.5) |

| Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga | 7 (5.1) |

| Hospital Universitario General de Valencia | 6 (4.3) |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña | 5 (3.6) |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander | 5 (3.6) |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid | 4 (2.9) |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia | 2 (1.4) |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó, Alicante | 1 (0.7) |

The general patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Myocardial revascularization, either isolatedly or accompanied by valve treatment, were the most frequent operations. With regard to the most relevant patient antecedents (Tables 2 and 3), mention must be made of the high percentage of patients presenting serious clinical disease before surgery, with NYHA functional class III and IV, preoperative critical conditions, the need for vasoactive drugs, or ventricular dysfunction with LVEF <35%. Many patients had suffered prior AMI (22 cases in the 90 days preceding surgery), percutaneous coronary intervention (PTCA/stent), previous CS, or moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension.

Demographic and general data.

| Patients with LCOS n=137 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender, % | Male/female | 65.2/34.8 |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 68.26±9.33 | |

| EuroSCORE II, mean±SD | 9.99±13 | |

| Comorbidities and risk factors, % | Hypertension | 70.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 63.5 | |

| Diabetes | 33.3 | |

| Smoker | 26.3 | |

| Severe pulmonary hypertension | 33.1 | |

| COPD | 10.9 | |

| Active endocarditis | 8 | |

| Type of surgery | Elective | 59.6 |

| Urgent | 33.8 | |

| Emergency | 6.6 | |

| Surgical procedures, % | Myocardial revascularization | 16.8 |

| Myocardial revascularization+valve surgery | 24.8 | |

| Aortic valve surgery | 11.7 | |

| Mitral valve surgery | 11.7 | |

| Mitral and aortic surgery | 8.1 | |

| Mitral and tricuspid surgery | 3.7 | |

| Others | 23.2 | |

As intraoperative factors associated to LCOS, we found that 70.1% of the patients required two or more vasoactive drugs on emerging from ECC. Pump reentry to secure definitive suspension of ECC proved necessary in 22 patients (16%). The mean ECC time was 147±60min, and the mean aortic clamping time was 105±43min. Prolonged surgical times, with ECC >120min, were recorded in 62.5% of the patients.

The above factors were compared among the different LCOS clinical diagnostic subgroups. In this regard, 46 patients met hemodynamic criteria of LCOS (group A), 50 complied with the clinical criteria (group B), and the rest (n=41) were diagnosed with cardiogenic shock (group C). No significant differences between groups were observed for most of the factors. However, differences were recorded in those patients with a more serious prior condition, such as the presence of resting angina, presurgical critical condition, NYHA functional class III and IV, the need for emergency surgery, and a high risk EuroSCORE II profile. The percentage of patients with prolonged surgical times (ECC >2h) was greater among those with cardiogenic shock (n=32; p=0.03). Likewise, the need for ECC reentry was more frequent in the cardiogenic shock patients (26.8%; p=0.05). Table 3 shows the distribution of the patients according to diagnostic group and the pre- and intraoperative variables.

Distribution of patients according to diagnostic subgroup and pre- and intraoperative variables.

| LCOS (n=46) | LCOS consistent clinical condition (n=50) | Cardiogenic shock (n=41) | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 15 (32.6) | 17 (34) | 15 (36.6) | 47 (34.3) | 0.925 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 31 (67.4) | 33 (66) | 26 (63.4) | 90 (65.7) | |

| Mean age in years | 68.7 | 67.96 | 68.59 | 68.26 | 0.91 |

| EuroSCORE II, mean | 5.58 | 9.33 | 15.83 | 9.99 | 0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 33 (72) | 35 (70) | 29 (71) | 97 (70.8) | 0.98 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 28 (61) | 29 (58) | 30 (73) | 87 (63.5) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 17 (37) | 21 (42) | 8 (20) | 46 (33.6) | 0.06 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 11 (24) | 14 (28) | 11 (27) | 36 (26.3) | 0.89 |

| COPD, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 6 (12) | 5 (12) | 15 (10.9) | 0.83 |

| Recent ischemic damage (3 months), n (%) | 10 (22) | 10 (20) | 13 (32) | 33(24.6) | 0.43 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 14 (30) | 13 (26) | 17 (41) | 44 (32.1) | 0.27 |

| Resting angina (CCS class 4), n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (6) | 7 (17) | 11 (8) | 0.03 |

| Previous PTCA/stent, n (%) | 7 (15) | 7 (14) | 9 (22) | 23 (16.8) | 0.56 |

| Depressed LVEF (<35%), n (%) | 14 (30) | 16 (32) | 15 (37) | 45 (33.8) | 0.89 |

| Presurgical NYHA III and IV, n (%) | 20 (43) | 24 (48) | 27 (66) | 71 (52.6) | 0.04 |

| Preoperative critical condition, n (%) | 6 (13) | 7 (14) | 13 (32) | 26 (19) | 0.04 |

| Valve disease with previous moderate-severe pulmonary hypertension, n (%) | 15 (33) | 17 (34) | 12 (29) | 44 (33.1) | 0.82 |

| Previous cardiac surgery, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 9 (18) | 11 (27) | 24 (17.5) | 0.08 |

| Active endocarditis, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (12) | 3 (7.3) | 11 (8) | 0.37 |

| Emergency surgery, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (17) | 9 (6.6) | 0.002 |

| ECC>120min, n (%) | 23 (50) | 30 (60) | 32 (78) | 85 (62.5) | 0.03 |

| ECC reentry, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 6 (12) | 11 (26.8) | 22 (16) | 0.05 |

Overall, the postoperative evolution of these patients was complicated, with important morbidity–mortality (Table 4).

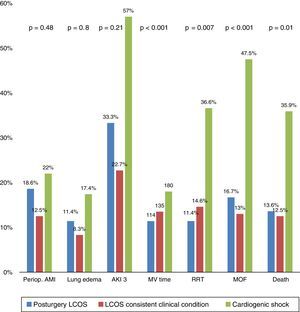

We examined whether the three clinical scenarios of LCOS proposed in the diagnostic definition of the consensus document6 could imply different clinical courses and prognoses. No statistically significant differences were observed between the subgroups regarding the number of patients requiring repeat surgery (due to bleeding or tamponade) or the incidence of arrhythmias or infectious, neurological, respiratory or gastrointestinal complications. It should be mentioned that although statistical significance was not reached, trends were observed, with inter-group differences (LCOS, LCOS consistent clinical condition and cardiogenic shock) in the rates corresponding to perioperative AMI (p=0.48), acute lung edema (p=0.80) and acute renal impairment (AKI stage 3; p=0.21). Significant differences were recorded in the duration of mechanical ventilation (p<0.001), in the percentage of patients requiring renal replacement therapy (p=0.007), in the proportion of patients who developed MOF over time (p<0.001), and therefore also in percentage mortality (p=0.01). Of note is the fact that the patients who developed MOF (n=32) were more numerous in the cardiogenic shock group (19 versus 7 in the LCOS group and 6 in the clinical diagnostic group; p<0.001). Fig. 2 graphically displays the differences in postoperative complications among the three diagnostic groups.

Different complications and evolution according to diagnostic subgroups. AKI 3: acute kidney injury 3; MOF: multiorgan failure; Periop. AMI: perioperative acute myocardial infarction; RRT: renal replacement therapy; MV time: duration of mechanical ventilation in minutes; LCOS: low cardiac output syndrome.

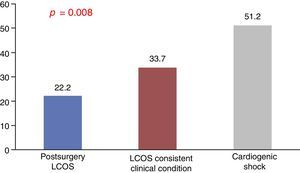

The analysis of the myocardial damage markers such as ultrasensitive troponin T and I likewise revealed no statistically significant differences. In contrast, the mean maximum lactate concentration (as a perfusion marker) (Fig. 3) and alanine aminotransferase levels were significantly higher in the patients with cardiogenic shock (51.2±49 versus 22.2±21 in group A and 33.7±36 in group B [p=0.002], referred to lactate, and 679.7±1040 versus 215±769 in group A and 167±358 in group B [p=0.008], referred to alanine aminotransferase). Lactate concentration reached statistical significance at all measurement timepoints (admission, p=0.001; 4h, p=0.014; 12h, p=0.012; 24h, p=0.01; 48h, p=0.003; discharge, p=0.01).

The analysis of the above data confirms the existence of increased patient severity, a greater percentage of complications, and a poorer prognosis among the patients with cardiogenic shock. It also must be noted that the evolution of the patients in the clinical diagnostic group was similar to that seen in the patients diagnosed through invasive monitoring.

DiscussionDespite the many patients subjected to CS and the relative incidence of postsurgery LCOS, few studies involving large patient samples have characterized this clinical form of AHF. The published studies analyze concrete aspects, and none have examined the clinical course according to the different clinical diagnostic subgroups. Our prospective multicenter study has analyzed patients with LCOS, differentiating three subgroups with evolutive and prognostic differences.

The literature describes a range of pre- and intraoperative factors related to LCOS. The study of Rao et al.,1 involving patients in the postoperative period of myocardial revascularization surgery, identified LVEF <20%, repeat surgery, the female gender, diabetes, age >70 years, left coronary trunk stenosis, recent AMI and triple vessel disease as independent predictors of the syndrome. Algarni et al.,7 in patients subjected to revascularization, identified repeat revascularization, surgery in the previous year, depressed LVEF (<40%), emergency surgery, cardiogenic shock and the female gender as predictive factors. These authors reported a decrease in the prevalence of LCOS over time. Ding et al.8 analyzed 205 patients with LCOS and found advanced age, depressed LVEF, surgery with ECC, emergency surgery and incomplete revascularization to be the factors associated to LCOS. The authors also described increased morbidity–mortality in these individuals. Very similar predictive factors were documented by Sa et al.9 in 89 patients with LCOS (14.7% coming from revascularization surgery).

Low cardiac output has also been related to the myocardial protection measures adopted during the surgical procedure. In this regard, Algarni et al.10 found the prevalence of LCOS to be significantly lower (p<0.001) in the group of patients revascularized using microplegia (2.7%) than in the group in which standard blood cardioplegia was used (5%). In a study of patients subjected to revascularization in which comparisons were made of the incidence of LCOS using cold (7°C) blood cardioplegia versus warm (29°C) cardioplegy,11 the authors found the incidence of the syndrome to be greater in the latter group. Likosky et al.,12 in a group of patients subjected to elective revascularization with ECC, examined the degree to which the surgeon and surgical practices influence the incidence of LCOS. The authors found the low cardiac output rates to vary among surgeons, and these variations could not be explained only on the basis of the case mix. This suggested that variability in perioperative practices (surgical times, cardioplegia, etc.) influences the risk of LCOS.

In a group of patients subjected to isolated mitral valve surgery, Maganti et al.13 identified the urgency of the operation, surgery in the previous year, LVEF <40%, NYHA functional class IV, ischemic mitral valve disease and clamping time as predictive factors.

In general, the published reviews14 contemplate the abovementioned pre- and intraoperative predictors. In our study, the analysis of the factors associated to the development of LCOS yielded results consistent with those found in the literature. Of note in our series is the observed association to pre- and also intraoperative clinical severity factors.

Knowing the risk factors for LCOS implies the need to identify high risk patients for the adoption of possible preventive measures. In this regard, preconditioning strategies are already being adopted in patients with ventricular dysfunction. The first experiences with the preoperative administration of levosimendan in selected patients have been encouraging.15,16 Trials are underway that will provide definitive results on the use of this drug in patient preconditioning.17 Recently, the LEVO-CTS trial has shown that levosimendan, used on a presurgical prophylactic basis in patients with LVEF ≤35% subjected to CS, does not result in a decrease in the combined target of diminished mortality, need for renal replacement therapy, perioperative AMI or the need for mechanical assist measures.18 On the other hand, cardioplegia and the different myocardial protection measures adopted during CS can modify the possible development of ventricular myocardial involvement due to ischemia/reperfusion or secondary myocardial stunning, and therefore the incidence of LCOS.19–23 In this way, patients at greater risk of suffering LCOS could be amenable to guided studies, with the adoption of specific cardioprotection measures.

On the other hand, the LCOS consensus document of the SEMICYUC 20126 distinguishes three clinical groups of LCOS. We sought to determine whether these three clinical scenarios proposed in the diagnostic definition of the document are associated to differences in clinical outcome. Comparisons were made of the diagnostic groups: (A) LCOS: “classical” definition with direct measurement of the cardiac index; (B) “consistent clinical condition” not based on invasive monitoring data; and (C) cardiogenic shock. In addition to the classical definitions of postoperative LCOS and cardiogenic shock, this classification includes a consistent clinical condition group not contemplated in other definitions. These three subgroups were compared in order to determine possible differences in terms of clinical evolution, complications and postoperative mortality. The results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. As has been commented under Results, differences between the subgroups were observed in the incidence of perioperative AMI, acute lung edema and acute renal functional impairment on the basis of percentage AKI stage 3 – though statistical significance was not reached, probably because of the limited number of patients involved. In contrast, statistically significant differences were recorded in the duration of mechanical ventilation, the need for renal replacement measures, the development of MOF and patient mortality. In this respect, the prognosis was clearly poorer among the patients with cardiogenic shock.

Two relevant findings were made in our study:

- 1.

The need to recognize the importance in routine practice of the “consistent clinical condition” diagnostic group. The assessment of clinical data such as oliguria and hypoperfusion, and of laboratory test data available in all centers (even on a point of care basis), such as lactate concentration and central venous oxygen saturation, allows the detection of low cardiac output in these patients. In this respect, advanced invasive monitoring (using a pulmonary artery catheter or transpulmonary thermodilution) might not be strictly necessary in all patients in order to diagnose and treat LCOS.24 In our study this “clinical” group showed a postoperative course characterized by a clear increase in morbidity–mortality very similar to that observed in the group of patients diagnosed on the basis of hemodynamic monitoring. Consequently, in terms of practical clinical management, we always must observe a high level of suspicion in order to start early and adequate treatment in this subgroup of patients (similar to that of the subgroup diagnosed through invasive monitoring).

- 2.

The clearly poorer clinical course and prognosis in the cardiogenic shock group versus the other two groups. Cardiogenic shock implies increased severity, with a poorer postoperative course, a greater incidence of MOF, and higher mortality. In patients that suffer shock, it must be considered that transesophageal echocardiography reveals right ventricular dysfunction in about 40% of the cases.25 This situation can imply changes in the management approach.26,27

In any case, LCOS is associated to important morbidity–mortality and postoperative complications (as reflected in the corresponding tables and figures). In our series, mortality was similar to that described in the literature, with significant differences depending on the mentioned diagnostic subgroups.

LimitationsAlthough our series involves a considerable number of patients, the sample is nevertheless limited and lacks a comparator control group. Furthermore, although over two-thirds of the participating Units claimed to follow the management algorithms of the consensus document, there were probably differences in patient treatment among the different centers. There consequently may have been a certain lack of homogeneity.

ConclusionsThe clinical evolution of patients with LCOS is complex, with important morbidity–mortality.

It is important to know the pre- and intraoperative factors that can lead to LCOS, with the aim of defining possible preventive strategies.

In our series, differences were found in the postsurgery clinical evolution parameters and in mortality among the different LCOS diagnostic subgroups.

Larger patient samples are required in order to confirm the results obtained.

AuthorshipAll the signing authors have made substantial contributions to study conception and design, data acquisition, and analysis and interpretation of the results. Likewise, they have participated in drafting of the manuscript or in critical review of its content, and have approved the final version of the article.

As applicable in the case of a working group, the rest of the participating or collaborating authors reflected in the table (ESBAGA study) and listed at the end of the document have participated in data acquisition.

Collaborators such as Dr. Ana Ochagavía-Calvo, Dr. Rafael Hinojosa-Pérez, Dr. Juan José Marín-Salazar, Dr. M. Victoria Boado-Varela and Dr. José Luis Romero-Luján contributed no patients, but participated in the conception and design of the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors:

Dr. José Luis Pérez-Vela (Hospital Universitario Doce de Octubre, Madrid), Dr. Juan José Jiménez-Rivera (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife), Dr. Miguel Ángel Alcalá-Llorente (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid), Dr. Begoña González de Marcos (Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid), Dr. Herminia Torrado (Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona), Dr. Francisco Javier González-Fernández (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Seville), Dr. Cristina García-Laborda (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Dr. M. Dolores Fernández-Zamora (Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga), Dr. Juan Carlos Martín-Benítez (Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, Madrid).

Collaborators, according to hospitals:

Hospital de Sabadell: Dr. Ana Ochagavía-Calvo. Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville: Dr. Rafael Hinojosa-Pérez. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña: Dr. Salvador Fojón-Polanco, Dr. Leticia Seoane-Quiroga, Dr. Miguel A. Solla-Buceta, Dr. M. Luisa Martinez-Rodriguez, Dr. M. Teresa Bouza-Vieiro, Dr. Alexandra Ceniceros-Barros. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander: Dr. Miguel F. Llano-Cardenal, Dr. Virginia Burgos-Palacios, Dr. Manuel Cobo-Belaustegui, Dr. Angela Canteli-Alvarez, Dr. Cristina Castrillo-Bustamante. Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia: Dr. Rubén Jara-Rubio, Dr. David Bixquert-Genovés, Dr. Carlos Albacete-Moreno. Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó, Alicante: Dr. Rafael Carrasco-Moreno, Dr. Teresa Arce-Arias. Hospital Universitario Doce de Octubre, Madrid: Dr. Silvia Chacón-Alves, Dr. Emilio Renes-Carreño, Dr. Teodoro Grau-Carmona. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife: Dr. José Luis Iribarren-Sarrias, Dr. M. Teresa Brouard-Martín, Dr. Samantha Huidobro, Dr. Javier Málaga-Gil, Dr. Carolina Garcia-Martin, Dr. Ramon Galvan. Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid: Dr. Anxela Vidal-González, Dr. César Pérez-Calvo, Dr. Renzo Portilla. Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona: Dr. Alain Pinseau-Castillo, Dr. Neus López-Suñé, Dr. Vicente Corral-Vélez, Dr. Nelson Betancur-Zambrano, Dr. Gabriel Moreno-González, Dr. Elisabeth Periche-Pedra. Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Seville: Dr. Sonia Ibáñez-Cuadros, Dr. Francisco Vela-Núñez, Dr. Cristina López Martín. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza: Dr. Pablo Gutierrez-Ibañes. Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid: Dr. Irene Garcia-Rico, Dr. Ricardo Andino-Ruiz, Dr. Judit Iglesias-Franco, Dr. Esther Díaz-Rodriguez, Dr. Nuria Arevalillo-Fernández, Dr. M. José Pérez-San José, Dr. Ana Gutiérrez-García. Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga: Dr. Teresa García-Paredes. Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca: Dr. Juan José Marín-Salazar. Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo (Vizcaya): Dr. M. Victoria Boado-Varela. Hospital Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas: Dr. José Luis Romero-Luján. Hospital General Universitario de Valencia: Dr. Juan Carlos Valía, Dr. Javier Hernández-Laforet.

The members of Grupo ESBAGA are listed in the Annex.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Vela JL, Jiménez Rivera JJ, Alcalá Llorente MÁ, González de Marcos B, Torrado H, García Laborda C, et al. Síndrome de bajo gasto cardiaco en el postoperatorio de cirugía cardiaca. Perfil, diferencias en evolución clínica y pronóstico. Estudio ESBAGA. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:159–167.