To evaluate mortality and functional status at one year of follow-up in patients >75 years of age who survive Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission of over 14 days.

DesignA prospective observational study was carried out.

SettingA Spanish medical–surgical ICU.

PatientsPatients over 75 years of age admitted to the ICU.

Primary variables of interestICU admission: demographic data, baseline functional status (Barthel index), baseline mental status (Red Cross scale of mental incapacity), severity of illness (APACHE II and SOFA), stay and mortality. One-year follow-up: hospital stay and mortality, functional and mental status, and one-year follow-up mortality.

ResultsA total of 176 patients were included, of which 22 had a stay of over 14 days. Patients with prolonged stay did not show more ICU mortality than those with a shorter stay in the ICU (40.9% vs 25.3% respectively, P=.12), although their hospital (63.6% vs 33.8%, P<.01) and one-year follow-up mortality were higher (68.2% vs 41.2%, P=.02). Among the survivors, one-year mortality proved similar (87.5% vs 90.6%, P=.57).

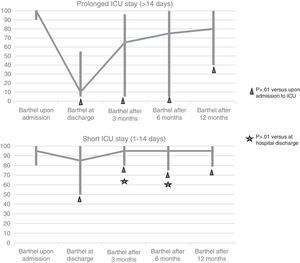

These patients presented significantly greater impairment of functional status at hospital discharge than the patients with a shorter ICU stay, and this difference persisted after three months. The levels of independence at one-year follow-up were never similar to baseline. No such findings were observed in relation to mental status.

ConclusionsPatients over 75 years of age with a ICU stay of more than 14 days have high hospital and one-year follow-up mortality. Patients who survive to hospital admission did not show greater mortality, though their functional dependency was greater.

Determinar la mortalidad y situación funcional al año de los pacientes mayores de 75 años con estancia en una unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) mayor de 14 días.

DiseñoEstudio prospectivo observacional.

ÁmbitoUCI médico-quirúrgica española.

PacientesPacientes mayores de 75 años ingresados en UCI.

Variables de interés principalesIngreso en UCI: datos demográficos, estado funcional basal (índice de Barthel), estado mental basal (Escala de incapacidad mental de la Cruz Roja), gravedad de la enfermedad (APACHE II y SOFA), mortalidad y estancia. Seguimiento al año: estancia/mortalidad hospitalaria, situación funcional y mental y mortalidad al año.

ResultadosIncluimos 176 pacientes, 22 con una estancia mayor de 14 días. Los pacientes con estancias prolongadas no presentaron mayor mortalidad en UCI que los de menor estancia (40,9% vs. 25,3%; p=0,12), aunque su mortalidad hospitalaria (63,6% vs. 33,8%; p<0,01) y al año (68,2% vs. 41,2%; p=0,02) fue superior. Entre los supervivientes la supervivencia al año fue similar (87,5% vs. 90,6%; p=0,57).

Estos pacientes presentaron un deterioro en su situación funcional al alta hospitalaria significativamente mayor que los de corta estancia, diferencia que se mantuvo a los 3 meses. Nunca llegaron a alcanzar niveles de independencia previos al ingreso durante el año. Estos hallazgos no se observaron a nivel mental.

ConclusionesLos pacientes mayores de 75 años con estancia en UCI mayor de 14 días presentan una mortalidad hospitalaria y al año elevada. Los pacientes que logran ser dados de alta del hospital no presentan mayor mortalidad, aunque sí presentan mayor grado de dependencia funcional.

There is growing interest in the sequelae of admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), though the data published to date in this regard are quite heterogeneous. Some authors1–5 have found such patients to have poorer quality of life and greater mortality than the gender- and age-matched general population until several years after admission to Intensive Care. In contrast, other investigators6–12 have observed acceptable recovery in the months following discharge from the ICU. A number of factors have been associated to increased morbidity-mortality after discharge from the ICU, including patient age,3,4,13,14 the duration of admission to the ICU,6,13 the severity of the disease condition,3,13,14 previous comorbidities, the basal situation of the patient,4 and the diagnosis motivating admission to the UCI.3,13

Considering the growing number of elderly patients admitted to our Units,15 a dilemma has developed regarding the long-term benefits of admission to the ICU in this population group. The literature offers conflicting results in this respect. Some studies have found that although mortality both in the ICU and after discharge from the Unit is high among elderly patients and greater than in younger individuals,3,7,13,15–17 functional status and quality of life one year after discharge among the survivors are very similar to how they were before admission to the ICU–thereby justifying admission to these Units.7,9,17 In contrast, other studies have described a clear worsening of quality of life among the survivors.16,18

The dilemma intensifies when considering elderly people who are admitted to the ICU for long periods of time. What are the mortality figures among these patients after discharge from the ICU? What is their functional status after discharge from the ICU? What quality of life do the survivors have? etc. Although there is no clear consensus as to what we mean by “prolonged admission” to the ICU–the definitions typically ranging from 2 to 4 weeks5,6,9,11–13,19,20–the literature shows that although mortality one year after discharge is high among survivors of prolonged admission to the ICU, their quality of life is good, with high rates of functional independence.6,8,12,13,16,17,21

The present study analyzes mortality and functional status after one year among elderly patients (over 75 years of age) with prolonged admission to the ICU (over 14 days), and establishes comparisons with elderly patients who have been admitted to the ICU for shorter periods of time.

Patients and methodsA prospective observational study was made in a 14-bed polyvalent ICU belonging to a tertiary hospital, covering a period of 18 months (from 1 December 2009 to 31 May 2011).

We included all patients over 75 years of age admitted to the ICU for more than 14 days and who agreed to participate in the study (through signing of the informed consent document by the patient/closest relatives).

At patient inclusion in the study we recorded the demographic variables (age and gender), comorbidities (as assessed by the Charlson comorbidity index22), basal functional status (as measured by the Barthel index [BI]23), basal mental state (measured using the Red Cross Psychic Disability scale [RCPD]24), place of residency, reason for admission to the ICU, and severity of the disease (evaluated by means of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II]25 and the Sequential-Related Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] scale26). At discharge from the ICU we collected information on stay and mortality in the Unit, the need for mechanical ventilation and its duration, the need for vasoactive drug support, and the presence of multiorgan failure (defined as a score of 3 or 4 on the SOFA scale26 referred to two or more organs). At hospital discharge we assessed mental and functional status, patient destination at discharge, and in-hospital stay and mortality.

The patients were followed-up on during one year after discharge from the ICU by means of a telephone interview at 3, 6 and 12 months, documenting mental and functional status (BI23 and RCPD scale24), mortality, place of residency and the number of hospital readmissions. On occasion of the interview after 12 months, the patients were asked whether they would be prepared to enter the ICU again if necessary.

Basal functional status was defined as the functional status of the patient in the month before admission, and the stay in the ICU was considered to be prolonged if it exceeded 14 days, and short if ≤14 days.

Functional status was divided into 5 levels according to the BI score23: total dependency (<20 points), severe dependency (20–35 points), moderate dependency (40–55 points), slight dependency (60–95 points), and independence (100 points). Dependent patients were regarded as those with total, severe or moderate dependency functional status (BI score23 <60). Significant worsening of functional status in turn was defined by a decrease in BI score23 of 20 points or more.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis of the results was carried out using the SPSS version 18.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Qualitative variables were reported as numbers and percentages, and were analyzed using the chi-squared test in the case of unpaired variables, and the McNemar test or McNemar–Bowker test in the case of paired binary variables of two or more categories, respectively. In the case of quantitative variables we first assessed normality of the distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Those variables exhibiting a normal distribution were reported as the mean±standard deviation, and were analyzed using the Student t-test for unpaired variables or the Student–Fisher test in the case of paired data. Quantitative variables with a non-normal distribution were reported as the median and interquartile range, and were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test or marginal homogeneity test (according to the number of categories) in the case of paired variables, and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test in the case of unpaired variables.

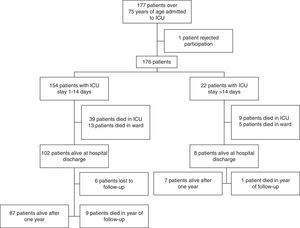

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 177 patients over 75 years of age were admitted to our ICU; of these subjects, one rejected participation in the study. Twenty-two of the 176 patients finally included in the study were admitted to the ICU for over 14 days (Fig. 1). Although there were no differences in terms of gender, comorbidities or basal mental and physical status, the patients requiring prolonged admission were younger and presented greater severity upon admission as measured by both the APACHE II25 and the SOFA26 scale. The main cause of admission to the ICU among the patients with prolonged admission was infectious disease (59.1%), while cardiovascular disease was seen to predominate among the short stay patients (59.7%). Table 1 shows the basal characteristics of the patients over 75 years of age upon admission to the ICU.

Basal characteristics of the patients over 75 years of age admitted to the ICU according to the duration of stay.

| Short stay (n=154) | Prolonged stay (n=22) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 81.82±4.19 | 79.27±2.86 | <0.01 |

| Age group | 0.08 | ||

| >75–80 years | 70 (45.5%) | 15 (68.2%) | |

| 81–85 years | 54 (35.1%) | 6 (27.3%) | |

| >85 years | 30 (19.5%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| Gender: male | 75 (48.7%) | 13 (59.1%) | 0.36 |

| Charlson scorea | 1.67±1.54 | 1.32±0.94 | 0.30 |

| Comorbidity | 0.32 | ||

| Low | 79 (51.3%) | 12 (54.5%) | |

| Moderate | 41 (26.6%) | 8 (36.40%) | |

| High | 34 (22.1%) | 2 (9.1%) | |

| Barthel indexb | 95.00 (80.00–100.00) | 100.00 (90.00–100.00) | 0.42 |

| Degree of functional dependency | 0.76 | ||

| Independent | 68 (49.6%) | 12 (54.5%) | |

| Slight dependency | 54 (39.4%) | 9 (40.9%) | |

| Moderate dependency | 10 (7.3%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| Severe dependency | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total dependency | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Functional dependency (BI < 60) | 15 (10.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0.70 |

| Red Cross psychic disability scale | 0.69 | ||

| Completely normal | 97 (71.9%) | 17 (77.3%) | |

| Slight disorientation in time | 15 (18.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Disorientation in time | 13 (9.6%) | 2 (9.1%) | |

| Reason for admission | <0.01 | ||

| Cardiovascular | 92 (59.7%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Infectious | 29 (18.8%) | 13 (59.1%) | |

| Respiratory | 5 (3.2%) | 3 (13.6%) | |

| Resuscitated cardiac arrest | 10 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Neurological | 6 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Intoxications | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| Digestive | 2 (1.3%) | 2 (9.1%) | |

| Surgery | 6 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Techniques | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| APACHE IIb | 16.50 (11.00–24.00) | 21.00 (19.00–28.25) | <0.01 |

| SOFAb | 5.00 (1.00–8.00) | 9.00 (7.00–12.00) | <0.01 |

The results are presented as number and percentage, except:

All the patients requiring prolonged admission to the ICU also required mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drug support, and 18.2% moreover required renal replacement therapy – all of them presenting multiorgan failure (Table 2). This situation in turn explained the increased severity among these patients, as reflected by a poorer daily SOFA score (Table 2).

Evolution of the patients during admission to the ICU according to the duration of stay.

| Short stay (n=154) | Prolonged stay (n=22) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of multiorgan failure | 56 (36.4%) | 22 (100.0%) | <0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 57 (37.0%) | 22 (100.0%) | <0.01 |

| Vasoactive drug support | 86 (55.8%) | 22 (100.0%) | <0.01 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (18.2%) | <0.01 |

| Poorer SOFA scorea | 5.00 (2.00–10.00) | 9.00 (8.75–12.00) | <0.01 |

| Stay in ICU (days)a | 3.00 (2.00–5.00) | 32.00 (17.00–45.25) | <0.01 |

| Hospital stay (days)a | 9.00 (6.00–16.00) | 52.00 (27.00–71.00) | <0.01 |

| Mortality in ICU | 39 (25.3%) | 9 (40.9%) | 0.12 |

| Mortality in hospital | 52 (33.8%) | 14 (63.6%) | <0.01 |

The results are presented as number and percentage, except:

Forty-eight patients died during admission to the ICU (global mortality rate in the ICU: 27.3%). Although the patients with prolonged admission suffered comparatively greater mortality, we observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 2).

After discharge from the ICU, 18 patients died during their stay in hospital–the in-hospital mortality rate being higher among the patients with prolonged admission (63.6% vs 33.8%; p<0.01). Functional deterioration was observed in the patients at hospital discharge, as evidenced by a drop in the BI score,23 which proved more notorious in the case of the patients with prolonged admission (BI23 100.00 [90.00–100.00] upon admission vs 10.00 [5.00–55.00] at hospital discharge; p<0.01). The BI score23 at discharge in these patients was lower than in the patients with short stays (BI23 at hospital discharge 85.00 [50.00–100.00] in patients with short stays vs 10.00 [5.00–55.00] in patients with prolonged stays; p<0.01), despite the absence of differences in this regard at the time of admission to the ICU. This decrease in BI score23 was significant (≥20 points) in all the patients with prolonged admission (100% vs 32.7%; p<0.01). A total of 4.5% of the patients in the prolonged admission group had been dependent before admission to the ICU, versus 10.9% of the patients with short admission (p=0.70). In turn, the dependency rate at hospital discharge was 85.7% in the prolonged admission group versus 28.8% in the short stay group (p<0.01).

In contrast, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of mental status at discharge versus mental status upon admission. In this regard, 77.3% of the patients with prolonged stays presented a normal mental status upon admission to the ICU, and this situation was seen to persist in 80% of them at discharge (p=0.35). In the case of the patients with short stays, 71.9% presented no mental alterations upon admission, and this situation persisted in 92.3% of them at discharge (p=0.08).

Follow-up after one yearA total of 79.8% of the patients with a short stay in the ICU were still alive at hospital discharge–a figure that dropped to only 53.8% among those with prolonged admission to the ICU (p=0.07). This difference in mortality was largely attributable to in-hospital deaths, since follow-up one year after hospital discharge showed 90.4% of the survivors to be still alive (87.5% of those in the prolonged admission group and 90.6% in the short stay group; p=0.57).

We observed no differences in the percentage of hospital readmissions during the year of follow-up between the two patient groups (100% in the patients with prolonged stays vs 74.5% in the patients with short stays; p=1.00).

On comparing the evolution of functional status among the patients according to the duration of admission to the ICU, we found the subjects with prolonged admission to have a poorer functional status both at hospital discharge (BI23 10.00 [5.00–55.00] vs 85.00 [50.00–100.00]; p<0.01) and after three months of follow-up (BI23 65.00 [5.00–96.25] vs 95.00 [80.00–100.00]; p=0.04) than the patients with short stays. Although an improvement in functional status was noted at 6 and 12 months in both groups, the differences between the patients with prolonged admission and those with short stays were not significant (Fig. 2). Despite the improvements at follow-up, 50% of the patients with prolonged admission to the ICU and 16.9% of those with short stays suffered significant loss of function (as reflected by a drop in BI score23 of ≥20 points) after one year with respect to the time of admission.

At one year of follow-up, functional status was found to be poorer than under basal conditions in both groups–though the loss of independence was more manifest (without reaching statistical significance) in the prolonged admission group, with an independency rate after one year of 66.7% versus 95.5% at the time of admission, while the short stay group showed an independency rate after one year of 85.1% versus 89.1% at the time of admission (Fig. 2).

With regard to patient mental status after one year, the subjects with prolonged stay in the ICU showed no differences at either discharge or after one year with respect to their mental status upon admission–most of the subjects maintaining normal mental function or with slight alterations referred to orientation in time, independently of the duration of stay in the ICU (Fig. 3).

Mental status. The figures show the evolution of mental status as scored with the Red Cross Psychic Disability scale in the course of the study in the two groups: prolonged admission and short stay. No significant differences were found on comparing the different moments of the study (basal, hospital discharge and follow-up during one year) in each group or between groups.

Seventy-five percent of the patients who survived prolonged admission to the ICU lived at home prior to admission, though only 37.5% returned home after hospital discharge. This percentage increased to 50% after one year of follow-up. In contrast, 68.4% of the patients who survived a short stay in the ICU returned home after discharge–a figure that increased to 75.7% after one year.

Only 49 patients answered the question as to whether they would be prepared to enter the ICU again if necessary because of the disease–no differences being observed according to the duration of admission to intensive care: 100% of the patients with prolonged admission to the ICU versus 76.1% of those with short stays stated that they would accept admission to the ICU again if necessary (p=1.00).

DiscussionIn our study we found the proportion of elderly patients with prolonged admission to the ICU to be low, though the mortality rates both in the ICU and in hospital were high and greater than among the patients with a short stay in the ICU. Furthermore, the patients in the prolonged admission group suffered important deterioration of functional status after hospital discharge, without recovery of their basal situation after one year of follow-up.

The mortality rate in the ICU in our series was 27.3%, which is consistent with the rates reported in the literature for elderly patients (23–62.5%)9,16,19,27–29–the published figures varying greatly according to the cutoff point considered (65–80 years). We recorded a tendency towards increased mortality in patients with prolonged admission, in coincidence with the findings of other studies both in adults6,12 and specifically in elderly subjects.19

Although the patients with prolonged admission presented greater severity upon admission to intensive care, and therefore also a poorer prognosis, they were found to be relatively younger. This age difference may have influenced the limitation of therapeutic effort, independently of the severity of the disease, with a possibly earlier decision to limit such effort in the older patients. Likewise, in-hospital mortality among the patients with prolonged admission to the ICU was found to be high and greater than in those with shorter stays. A review of the literature yielded no similar studies allowing comparisons to be made with our own mortality figures. We only identified two studies in patients over 70 years of age and with stays of over 30 days. The respective mortality rates were 33% and 23%, with no statistically significant differences versus patients with shorter stays.9,19

Despite the high in-hospital mortality recorded in our study, most of the patients who survived admission to hospital were still alive after one year. Montuclard et al.9 reported a similar estimated survival rate of 41±6% after one year in patients over 70 years of age and with stays of more than 30 days.

On examining what happens with the survivors in relation to functional status, the latter was seen to have clearly worsened at the time of hospital discharge, and although the situation improved over the following months (particularly in the first three months of follow-up), functional status failed to return to the levels observed prior to admission to the ICU. This deterioration was more notorious in the patients with prolonged admission. Few studies have analyzed functional status over the long term in elderly patients who survive admission to the ICU, and the results are moreover heterogeneous.16,17,30–33 Only one study has examined what happens in elderly subjects who survive prolonged (>30 days) admission to the ICU.9 The authors recorded a worsening of general functional status (except as regards eating) 557±117 days after discharge from the ICU, though most of the patients remained independent for their activities of daily living. This coincides with our own observations, since 60% of the patients with prolonged admission were found to be independent after one year of follow-up. In our case, the situation among the patients with prolonged admission to intensive care was worse than in those with short stays, with lower independence rates, and therefore with fewer subjects able to return home during the first year after discharge.

We observed no significant differences in patient mental status after versus before hospital admission, not even after one year of follow-up, independently of the duration of admission to the ICU. No studies have been made on the mental sequelae after one year in elderly patients with prolonged admission to the ICU.

As regards the question of whether the patients with prolonged admissions would be willing to enter the ICU again if necessary, we found that most of the survivors would accept readmission. Similar results have been obtained by Montuclard et al.,9 since 83.3% of their elderly patients who were still alive one year after prolonged admission to the ICU would accept returning to the ICU if necessary.

As regards the limitations of our study, mention must be made of its single-centre nature, with a limited number of patients who were moreover selected on the grounds of a good basal status (both mental and physical), and with low comorbidity as previously described34 and also seen in similar studies.16,28,35,36 Furthermore, we did not record the limitation of therapeutic effort rates, which could have been interesting for better analysis of the data.

In conclusion, we found that patients over 75 years of age with prolonged admission to the ICU suffer high mortality both in the ICU and in hospital, and such mortality is moreover greater than in patients requiring shorter stays in intensive care. Nevertheless, the survivors of prolonged admission to the ICU show a high survival rate after one year–though functional status is poorer than before admission to the ICU, despite slight improvement during the year of follow-up.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks are due to all the patients and personnel members who made this study possible.

Please cite this article as: Pintado MC, Villa P, Luján J, Trascasa M, Molina R, González-García N, et al. Mortalidad y estado funcional al año de pacientes ancianos con ingreso prolongado en una unidad de cuidados intensivos. Med Intensiva. 2016;40:289–297.