Vascular catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) is associated to increased patient morbidity-mortality and healthcare costs.1 Different measures have therefore been proposed to try to prevent it.2,3 A meta-analysis has shown the application of a series of measures to result in an important decrease in the incidence of CRB in many studies worldwide.4

The Bacteremia Zero project implemented in 2009 reduced the incidence of CRB,5 comprising bloodstream infection of unknown origin and bacteremia secondary to central venous catheter (CVC) placement, from 4.9 to 2.8 cases per 1000 days of CVC, and from 2.7 to 1.4 per 1000 days of CVC, respectively.5 These rates have been maintained over time, possibly with the help of implementation of the Pneumonia Zero,6 Resistance Zero7 and Urinary tract infection Zero projects.8 The measures for the prevention of CRB include adequate hand hygiene, optimum barrier measures, skin disinfection with chlorhexidine, preference for subclavian access, withdrawal of needless catheters, and hygienic handling of catheters.6

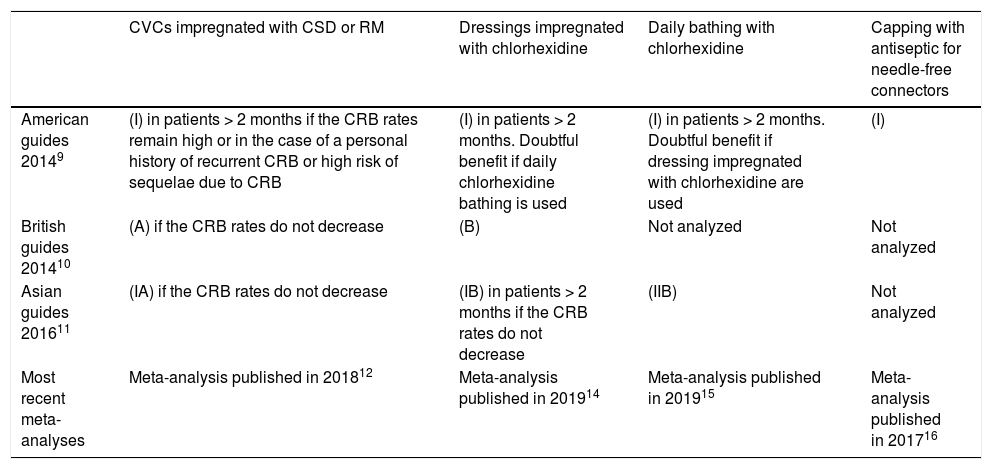

During these 10 years of implementation of the Bacteremia Zero project, new evidence has emerged referred to certain non-proposed measures such as CVCs impregnated with antimicrobials, dressing impregnated with chlorhexidine, daily chlorhexidine bathing and capping with antiseptic for needle-free connectors. Such measures have been proposed by the clinical practice guides (CPGs) of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) published in 2014,9 the UK Department of Health published in 2014,10 and the Asia Pacific Society of Infection Control (APSIC) published in 201611 (Table 1). The challenge therefore arises to continue reducing the current CRB rates.

Recommendations of different scientific societies and new evidence on measures for the prevention of vascular catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) following implementation of the Bacteremia Zero project.

| CVCs impregnated with CSD or RM | Dressings impregnated with chlorhexidine | Daily bathing with chlorhexidine | Capping with antiseptic for needle-free connectors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American guides 20149 | (I) in patients > 2 months if the CRB rates remain high or in the case of a personal history of recurrent CRB or high risk of sequelae due to CRB | (I) in patients > 2 months. Doubtful benefit if daily chlorhexidine bathing is used | (I) in patients > 2 months. Doubtful benefit if dressing impregnated with chlorhexidine are used | (I) |

| British guides 201410 | (A) if the CRB rates do not decrease | (B) | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

| Asian guides 201611 | (IA) if the CRB rates do not decrease | (IB) in patients > 2 months if the CRB rates do not decrease | (IIB) | Not analyzed |

| Most recent meta-analyses | Meta-analysis published in 201812 | Meta-analysis published in 201914 | Meta-analysis published in 201915 | Meta-analysis published in 201716 |

The level of evidence of each measure for preventing CRB according to each clinical practice guide is indicated in parentheses.

CRB: vascular catheter-related bacteremia; CSD: chlorhexidine / silver sulfadiazine; CVC: central venous catheter; RM: rifampicin - minocycline.

The American,9 British10 and Asian CPGs11 recommend the use of catheters impregnated with antimicrobials if the CRB rates remain high. A meta-analysis published in 201812 including 25 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and 9368 CVCs (4001 standard catheters, 2598 catheters impregnated with chlorhexidine / silver sulfadiazine, 1635 impregnated with silver, and 1134 impregnated with rifampicin and miconazole or minocycline) found CVCs impregnated with chlorhexidine / silver sulfadiazine (odds ratio [OR]=0.64; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]=0.40–0.96) or antibiotics (OR=0.3; 95%CI=0.25–0.95) to pose a lesser risk of CRB than standard catheters. However, there were no significant differences between CVCs impregnated with silver and standard catheters (OR=0.77; 95%CI=0.46–1.27).

Limitations for the use of impregnated CVCs comprise possible allergies to the antimicrobial (isolated cases) or infections caused by microorganisms resistant to the drug (in in vitro studies and animal models).13

Dressings impregnated with chlorhexidineThe American,9 British10 and Asian CPGs11 recommend the use of dressings impregnated with chlorhexidine. A meta-analysis published in 201914 including 11 RCTs and 10,796 catheters (CVCs, arterial catheters and tunneled catheters) concluded that impregnated dressings reduce the risk of CRB (OR=0.60; 95%CI=0.42–0.85). However, the studies posed the limitation of including different types of catheters (CVCs, arterial catheters and tunneled catheters) and catheter insertion sites associated with different CRB risks; furthermore, the protective effect for each catheter type and site was not determined.

Dressings impregnated with chlorhexidine also have the inconvenience of possible allergies or infections caused by microorganisms resistant to chlorhexidine. On the other hand, none of the RCTs of the meta-analysis reported the incidence of resistances; only three of the trials reported the incidence of contact dermatitis (approximately 5% and particularly affecting newborn infants with a weight of under 1kg and less than four months of age); and no systemic reactions to chlorhexidine were reported.

Bathing of the patient with chlorhexidineBathing of the patient with chlorhexidine is advised by the American9 and Asian CPGs,11 and is not analyzed in the British guides.10 A meta-analysis published in 201915 involving 26 studies (8 RCTs and 18 observational studies) analyzed the effect of daily bathing with chlorhexidine. Eighteen studies used disposable sponges with 2% chlorhexidine, while 8 studies used chlorhexidine solutions (at a concentration of 4% in 5 studies, 2% in two studies, and 0.9% in one study). The incidence of CRB was seen to be lower with daily chlorhexidine bathing than when soap and water were used (incidence rate ratio=0.59; 95%CI=0.52–0.68).

The possible limitations referred to the appearance of allergies or infections caused by microorganisms resistant to chlorhexidine were not analyzed in the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Capping with 70% isopropyl alcohol for needle-free connectorsThe American CPGs9 recommend this practice, while the British10 and Asian guides do not analyze its use.11 A meta-analysis published in 201716 involving 7 observational studies (with a before-after implementation design) recorded a decrease in CRB (incidence rate ratio=0.59; 95%CI=0.45–0.77) associated to the use of capping with antiseptic versus standard capping – though the appearance of allergies to the antiseptic was not analyzed.

Proposal for reducing the current vascular catheter-related bacteremia ratesAs in the case of the Pneumonia Zero project, there are both mandatory measures and optional measures. The four measures for preventing CRB (impregnated CVCs, impregnated dressings, chlorhexidine bathing and capping with antiseptic) could be incorporated to the Bacteremia Zero initiative as optional measures. The current mandatory measures of the Bacteremia Zero project certainly must be maintained, in view of the outcomes they afford. Each individual center should decide the need to adopt optional measures, the types of measures, and the kind of patients in which they should be applied. Optional measures possibly are indicated in those units that despite adequate compliance with the mandatory measures present CRB rates (encompassing bacteremia of unknown origin and secondary to CVC) of over three episodes per 1000 days of CVC, in accordance with the quality standard proposed by the SEMICYUC in 2017 (ht*tps://w*ww.bing.com/search?PC=WCUG&FORM=WCUGDF&q=indicadoresdecalidad2017_semicyuc_spa-1.pdf). We could start by adopting some of the mentioned measures, with a view to securing increased efficiency (I personally would recommend impregnated CVCs, which moreover represent the optional measure with the greatest supporting evidence according to the latest CPGs10–12). Likewise with a view to securing increased efficiency, we could start by applying the chosen optional measure in concrete clinical scenarios: 1) patients at increased risk of CRB (immune depressed subjects, altered skin integrity); 2) vascular accesses posing an increased risk of CRB (jugular vein with tracheostomy or femoral vein)14; and 3) patients at an increased risk of suffering complications if CRB develops (recent implantation of heart valves or aortic prostheses). Depending on whether or not the quality standard is reached after adopting the optional measure in the selected clinical scenarios, we could decide application of the measure to the rest of the patients, or adopt other optional measures in the selected clinical settings.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lorente L. Reducir las tasas actuales de bacteriemia relacionada con catéter tras la implantación de los programas Zero: este es el reto. Med Intensiva. 2021;45:243–245.