To investigate the prediction of 30-day mortality by frailty and comorbidity in a mixed ICU population and monitor the implementation of the Clinical Frailty Scale as daily practice in the ICU.

DesignA prospective observational single-center cohort study.

SettingMixed ICU at Zealand University Hospital.

PatientsAll patients >40 years of age acutely admitted to the ICU from April 1st 2021 to March 31st 2022.

Main variables of interestFrailty assessed by the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), Comorbidity-Polypharmacy-Score (CPS), and 30-day mortality.

ResultsA total of 319 patients were included in the study. Of these, 118 (37%) were categorized as frail, defined by a CFS ≥ 5. The CPS score was median (IQR) 13 (7–18), rated as moderate. Patients with increasing frailty demonstrated higher CPS scores. The overall 30-day mortality was 34.5%. Patients categorised as frail had a higher 30-day mortality compared to non-frail patients (47% vs 27%). The AUROC of CFS and CPS of 30-day mortality was 0.77 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.83) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.81), respectively. Combining CFS and CPS did not strengthen the ability to predict 30-day mortality compared to CFS alone. ICU clinicians assessed CFS in 79% of patients.

ConclusionFrailty assessed by CFS had a fair prediction of 30-day mortality after ICU admission in a mixed ICU population. The discriminatory ability for predicting 30-day mortality was not improved by combining CFS and CPS compared to CFS alone.

The clinical implementation of the CFS was performed effectively.

Investigar la predicción de la mortalidad a 30 días por fragilidad y comorbilidad en una población mixta de UCI y monitorear la implementación de la Escala de Fragilidad Clínica como práctica diaria en la UCI.

DiseñoUn estudio de cohorte observacional prospectivo de un solo centro.

ÁmbitoUCI mixta en el Hospital Universitario de Zelanda.

PacientesTodos los pacientes >40 años ingresados de forma aguda en la UCI desde el 1 de abril de 2021 hasta el 31 de marzo de 2022.

Variables de interés principalesFragilidad evaluada mediante la Escala de Fragilidad Clínica (CFS), la Escala de Comorbilidad-Polifarmacia (CPS) y la mortalidad a 30 días.

ResultadosUn total de 319 pacientes fueron incluidos en el estudio. De estos, 118 (37%) fueron categorizados como frágiles por la CFS. La puntuación de la CPS fue mediana (RIC) 13 (7–18) (calificada como moderada). Los pacientes con fragilidad creciente (CFS ≥ 5) demostraron puntuaciones más altas en la CPS. La mortalidad general a 30 días fue del 34,5%. Los pacientes categorizados como frágiles tuvieron una mortalidad a 30 días más alta en comparación con los pacientes no frágiles (47% vs 27%). El AUROC de la CFS y la CPS de mortalidad a 30 días fue de 0.77 (IC del 95%: 0.72 a 0.83) y 0.75 (IC del 95%: 0.69 a 0.81) respectivamente. La combinación de la CFS y la CPS no fortaleció la capacidad de predecir la mortalidad a 30 días en comparación con la CFS sola. CFS fue evaluado por los médicos de la UCI en el 79% de los pacientes.

ConclusionesLa fragilidad evaluada mediante la CFS predijo adecuadamente la mortalidad a los 30 días tras el ingreso en UCI en una población mixta. La capacidad discriminatoria para predecir la mortalidad a los 30 días no se vio reforzada al combinar la CFS y la CPS, en comparación con la CFS sola. La aplicación clínica de la CFS fue eficaz.

An increasingly ageing and co-morbid population challenges the capacity of both hospitals and intensive care units (ICU).1,2 Simple factors like age assessed individually are not an ideal predictor for outcomes in the ICU.3 Hence, more research is needed to identify predictive tools that account for both function and co-morbidity and are easy to use in the clinical setting to identify patients who will benefit from critical care in the ICU.

Frailty and comorbidity are essential factors influencing the outcomes of critical illness.3–5 Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a 9-level scale indicating the level of frailty; CFS ≥ 5 indicates frailty.6,7 The scale has previously been shown to be easy to use and has demonstrated good inter-rater reliability.5,8 The Comorbidity-Polypharmacy Score (CPS) generates an overall score that includes both comorbidity and use of medication.9 The severity of the score is categorised into four groups: minor (0–7), moderate (8–14) severe (15–21). and morbid (≥22).10 CPS has also been validated in critically ill populations, demonstrating higher CPS scores associated with increased mortality.11

The two tools provide different aspects of the patient´s pre-admission status. CFS categorises the functional status and how the patient copes with everyday life, whereas CPS quantifies comorbidities and scales them according to total medication. Together, these instruments may provide a more comprehensive picture of the health and functional status of the individual patient. Combining the CFS and CPS in a mixed ICU population has only been examined for patients aged 80 years and above and did not improve prediction on mortality, but it may prove predictive value in outcomes in patients with a broader age span.5

This study aimed to investigate the prediction of 30-day mortality by CFS and CPS in a mixed ICU population. Secondly, we aimed to describe the clinical implementation of CFS assessment by ICU clinicians.

Our hypothesis was that CPS and CFS in combination were superior to either CPS or CFS alone at predicting 30-day mortality in a mixed ICU population. Finally, we hypothesised that the CFS would be performed in 80% of the ICU patients in the clinical setting.

Patients and methodsStudy designThe study was a prospective observational single-center cohort study at Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark. The ICU is a level 3 ICU with approximately 500 acute admissions per year of both medical and surgical patients.12

EthicsThe study was designed as a quality development project, so permission to collect data was limited to a one-year period. According to the National Ethics Committee (EMN-2021-01961) and Danish law, individual patient consent was not needed. Data collection was performed in accordance with the Danish Data Protection Agency's (REG-015-2021) regulations.

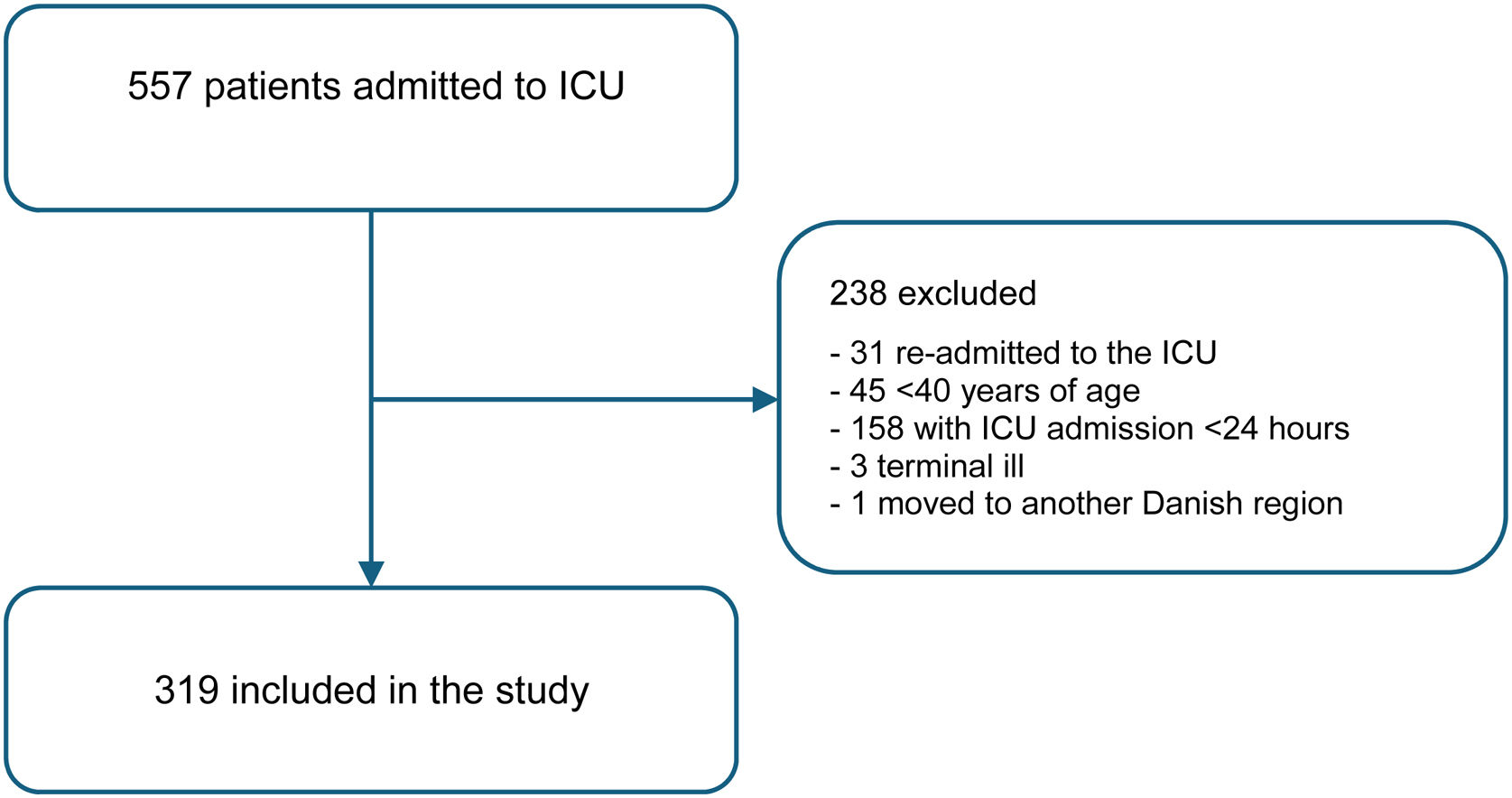

PopulationThe study included patients aged 40 years and above admitted to the ICU from April 1st, 2021, to March 31st, 2022. Only ICU patients admitted with acute critical illness were included. For patients experiencing multiple ICU admissions during the inclusion period, only the primary admission was included. Exclusion criteria were ICU length of stay (LOS) less than 24 h, and admission for terminal care.

OutcomesThe primary outcome was all-cause 30-day mortality.

Secondary outcomes were:

- •

Prediction of 30-day mortality by CFS and CPS (AUROC)

- •

ICU length of stay

- •

Hospital length of stay

- •

Days on ventilator

- •

Differences in pre- and post-admission residential status

- •

Percentage of patients assessed by the ICU clinicians at ICU admission by the CFS.

Data was obtained from the electronic patient data management system (EPIC, Wisconsin, USA) and entered into a secured database with a pseudo-anonymised trial identification number.

The baseline variables included age, sex, height, weight, pre-admission residential status, days in hospital before ICU admission, pre-admission medical prescriptions, pre-admission comorbidities, admission type, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) 3 and pre-ICU-admission withholding of life-sustaining treatments (withholding non-invasive ventilation (NIV), invasive mechanical ventilation, or dialysis).

As predictive variables, CFS and CPS scores were registered within the first 48 h of ICU admission.

All ICU physicians were thoroughly instructed in performing the CFS, including completing an e-learning module.8,13 Furthermore, posters explaining the CFS were strategically placed in various locations throughout the department, particularly near the clinicians’ workstations, to support the performance of the CFS assessments. Additionally, one of the authors was in the department almost every weekday, available to discuss the frailty scores of the patients. Based on the overall functional status and medical history of the patient, one month pre-admission, the attending physicians assessed the CFS within the first 48 h of ICU admission. Because most ICU patients were unable to provide personal information, the score was based on information from the patient's electronic records and correspondence with the next of kin or municipal care personnel.5 If the CFS score of a patient was not evaluated within the first 48 h, one of the investigators not involved in the patient's treatment would receive anonymised copies of the patient's pre-admission electronic records and information provided by the next of kin to evaluate the CFS score. This workflow was performed to ensure blinding of the evaluation.

The CPS was obtained by reviewing medical charts and pharmacy records and was calculated by one of the investigators. The calculation was performed based on the total number of pre-admission medical drug prescriptions, including over-the-counter medication, plus all known co-morbidities listed in the electronic patient data management system.

During the ICU admission, the use of invasive mechanical ventilation, duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU Length Of Stay (LOS), withholding of life-sustaining treatment during ICU stay (withholding NIV, invasive mechanical ventilation, or dialysis) and ICU mortality were registered. Following discharge, Hospital LOS, residential status and 30-day mortality were obtained.

Statistical analysisThis study is regarded as exploratoryData were described using mean and standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution, and with proportions where relevant. For correlation analyses, the Spearman rank order correlation was applied for ordinal and non-parametric outcomes. The association between CFS and outcomes was performed by linear and logistic regression. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Confidence intervals were calculated using the binomial proportion.

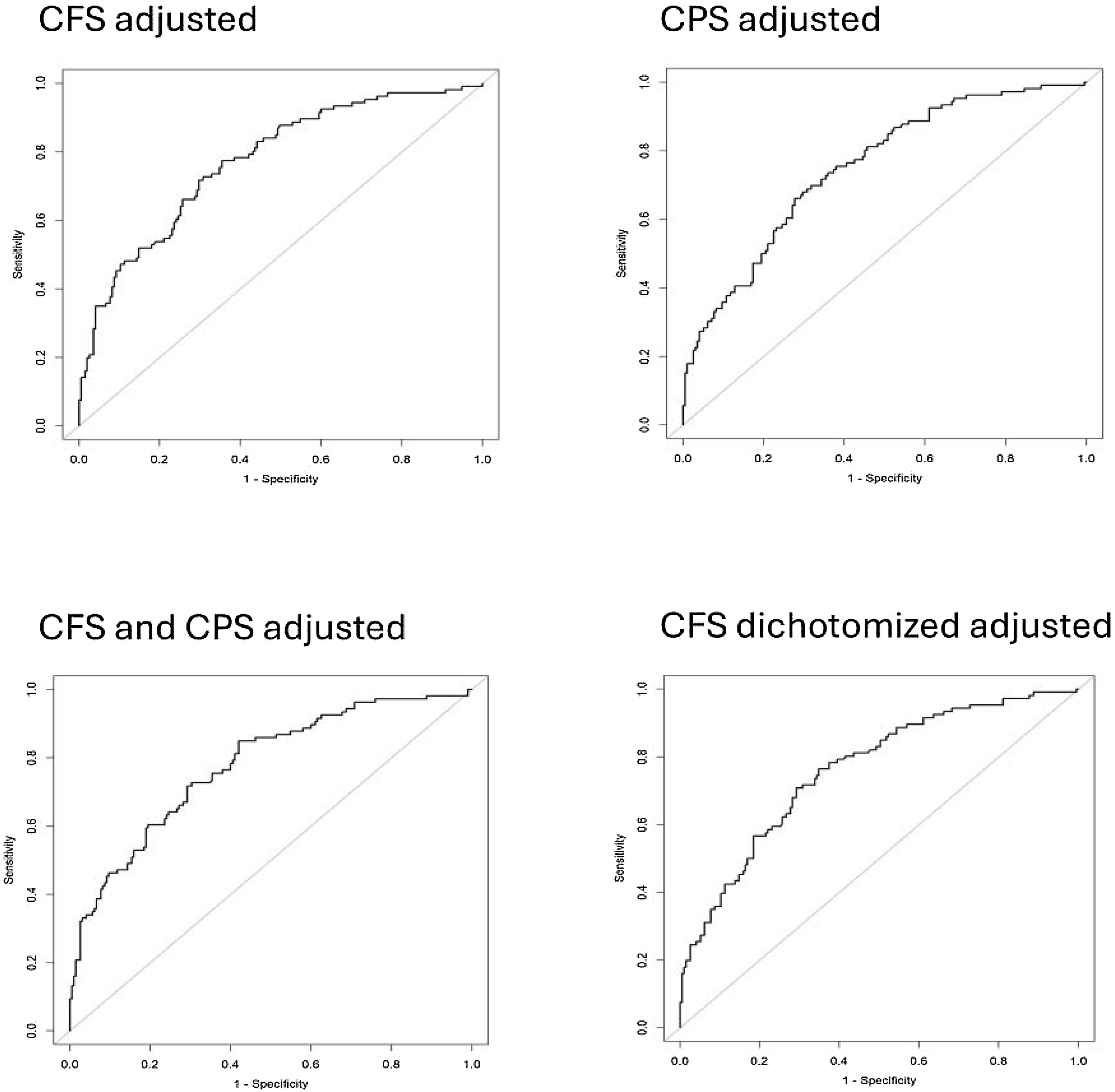

The ability of CFS and CPS, individually and in combination, to predict 30-day mortality was analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The ROC curves were performed for CFS as a categorical variable, for CPS as a continuous variable, and subsequently for CFS dichotomised as non-frail and frail. The analyses were performed unadjusted and, in complete cases, adjusted for the following confounders: age, sex, SAPS3 and pre-ICU-admission withholding of life-sustaining treatments. An area under the ROC curve (AUROC) less than 0.7 is regarded as poor performance. An AUROC of 0.70 – 0.80 is considered fair performance, and an AUROC greater than 0.8 is excellent performance.14

Furthermore, a calibration performance plot for the adjusted prediction by CFS was created to assess model calibration. The slope of an ideal calibration curve is 1.0, whereas values below 1.0 describe a prediction model with a risk of overestimating risk, and values above demonstrate a risk of underestimating risk.15 To evaluate the accuracy of the prediction, we applied the Brier score. The score ranges from 0 to 1; a score of 0 represents perfect prediction, and a score of 1 is entirely inaccurate.16

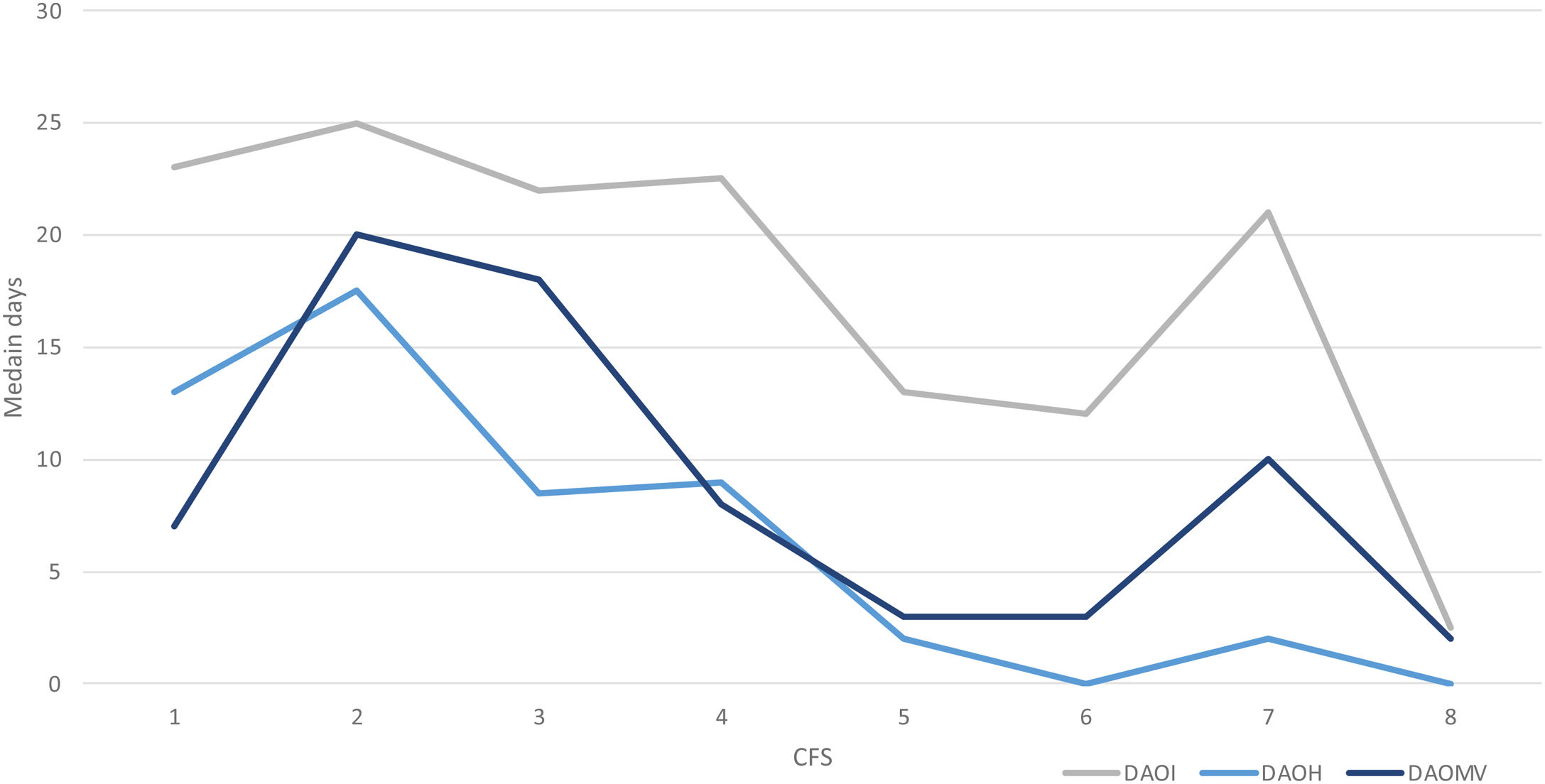

To account for patients dying during admission, thus affecting time on ventilator and LOS, we calculated Days Alive and Off Mechanical Ventilation in 30 days (DAOMV), Days Alive and Out of ICU in 30 days (DAOI), and Days Alive and Out of Hospital in 30 days (DAOH). DAOMV was calculated as the number of days alive from ICU admission minus the number of days on mechanical ventilation. If the patient did not die, the number of days alive would be 30 days.

DAOI and DAOH were calculated as the days alive from ICU admission subtracted ICU LOS, and as the days alive from ICU admission subtracted hospital LOS, respectively.

Subgroup analyses of age and admission type were performed to account for the heterogeneity of the population.

Statistical analyses were made in R, version 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2022).

ResultsFrom April 1 st 2021 until March 31 st 2022, 557 patients were admitted to the ICU. Of these, 238 (43%) were excluded, leaving 319 (57%) patients included in the study (Fig. 1). Two-thirds of the excluded patients were admitted for less than 24 h, and other reasons for exclusion included readmissions and patients being under 40 years of age. ICU clinicians rated CFS in 79% (n = 253) of patients, while the investigator rated it in 21% (n = 66). The proportion of CFS rated by the clinicians remained stable throughout the year of data collection (Electronic Supplemental Material (ESM), S1). At the time of data collection conclusion, 22 patients were still admitted to the ICU at day 30 (15 non-frail patients and seven frail patients), and 52 patients were still admitted to the hospital at day 30 (40 non-frail and 12 frail).

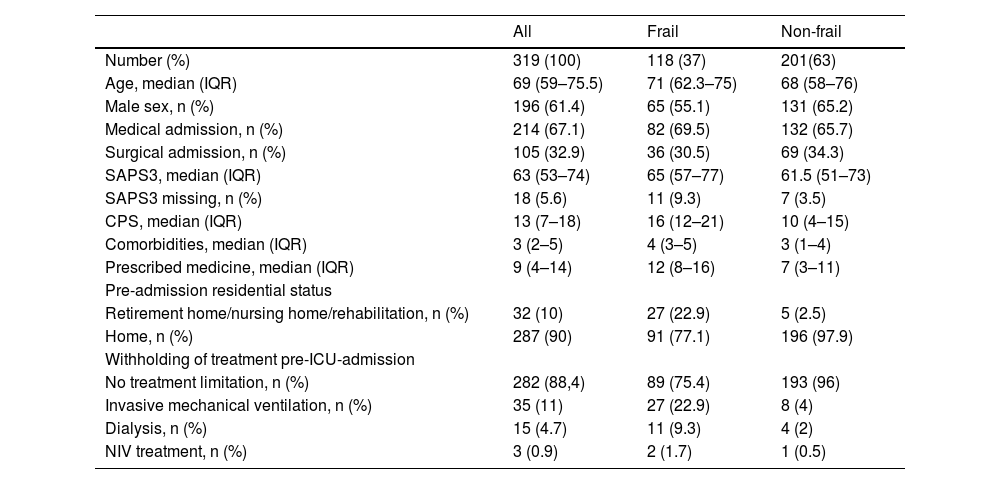

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and ESM S2. Approximately 62% (197) of the population consisted of males. The median age was 69 years (IQR 59–75). Of the 319 patients, 282 (88.4%) did not have any pre-ICU-admission limitation of life-sustaining treatment (ESM, S13). The most abundant pre-ICU-admission limitation was invasive mechanical ventilation (Table 1)

Baseline characteristics.

| All | Frail | Non-frail | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 319 (100) | 118 (37) | 201(63) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 69 (59–75.5) | 71 (62.3–75) | 68 (58–76) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 196 (61.4) | 65 (55.1) | 131 (65.2) |

| Medical admission, n (%) | 214 (67.1) | 82 (69.5) | 132 (65.7) |

| Surgical admission, n (%) | 105 (32.9) | 36 (30.5) | 69 (34.3) |

| SAPS3, median (IQR) | 63 (53–74) | 65 (57–77) | 61.5 (51–73) |

| SAPS3 missing, n (%) | 18 (5.6) | 11 (9.3) | 7 (3.5) |

| CPS, median (IQR) | 13 (7–18) | 16 (12–21) | 10 (4–15) |

| Comorbidities, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) | 3 (1–4) |

| Prescribed medicine, median (IQR) | 9 (4–14) | 12 (8–16) | 7 (3–11) |

| Pre-admission residential status | |||

| Retirement home/nursing home/rehabilitation, n (%) | 32 (10) | 27 (22.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Home, n (%) | 287 (90) | 91 (77.1) | 196 (97.9) |

| Withholding of treatment pre-ICU-admission | |||

| No treatment limitation, n (%) | 282 (88,4) | 89 (75.4) | 193 (96) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 35 (11) | 27 (22.9) | 8 (4) |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 15 (4.7) | 11 (9.3) | 4 (2) |

| NIV treatment, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) |

Baseline characteristics according to frailty (CFS ≥ 5) vs. non-frail (CFS < 5).

CFS: Clinical Frailty Score, CPS: Clinical Polypharmacy Score, SAPS3: Simplified Acute.

Physiology Score 3.

Thirty-seven per cent (n = 118) of the patients were assessed as frail (CFS ≥ 5). Of these, male sex constituted 55% versus 66% of the non-frail population. The frail patients were more often admitted to hospital from a nursing home, 22.9 % and 2.5 %, respectively, and the frail patients experienced to a greater extent pre-ICU-admission limitation of life-sustaining treatment, 24.6 % versus 4 % (Table 1)

The median CPS score for frail patients was 16 (IQR 12–21), rated as severe, compared to a median score of 10 (IQR 4–15) for non-frail patients, rated as moderate (Table 1). Patients with increasing frailty demonstrated higher CPS scores (ESM S3). Spearman correlation analysis displayed a moderate correlation between CPS and CFS (ρ = 0.52). We found that frail patients had approximately the same number of comorbidities as non-frail patients (median 4 [IQR 3–5] vs. 3 [IQR 1–4]). The frail did, however, have a median of 12 (IQR 8–16) medical drug prescriptions, whereas the non-frail patients had a median of 7 (IQR 3–11) (Table 1).

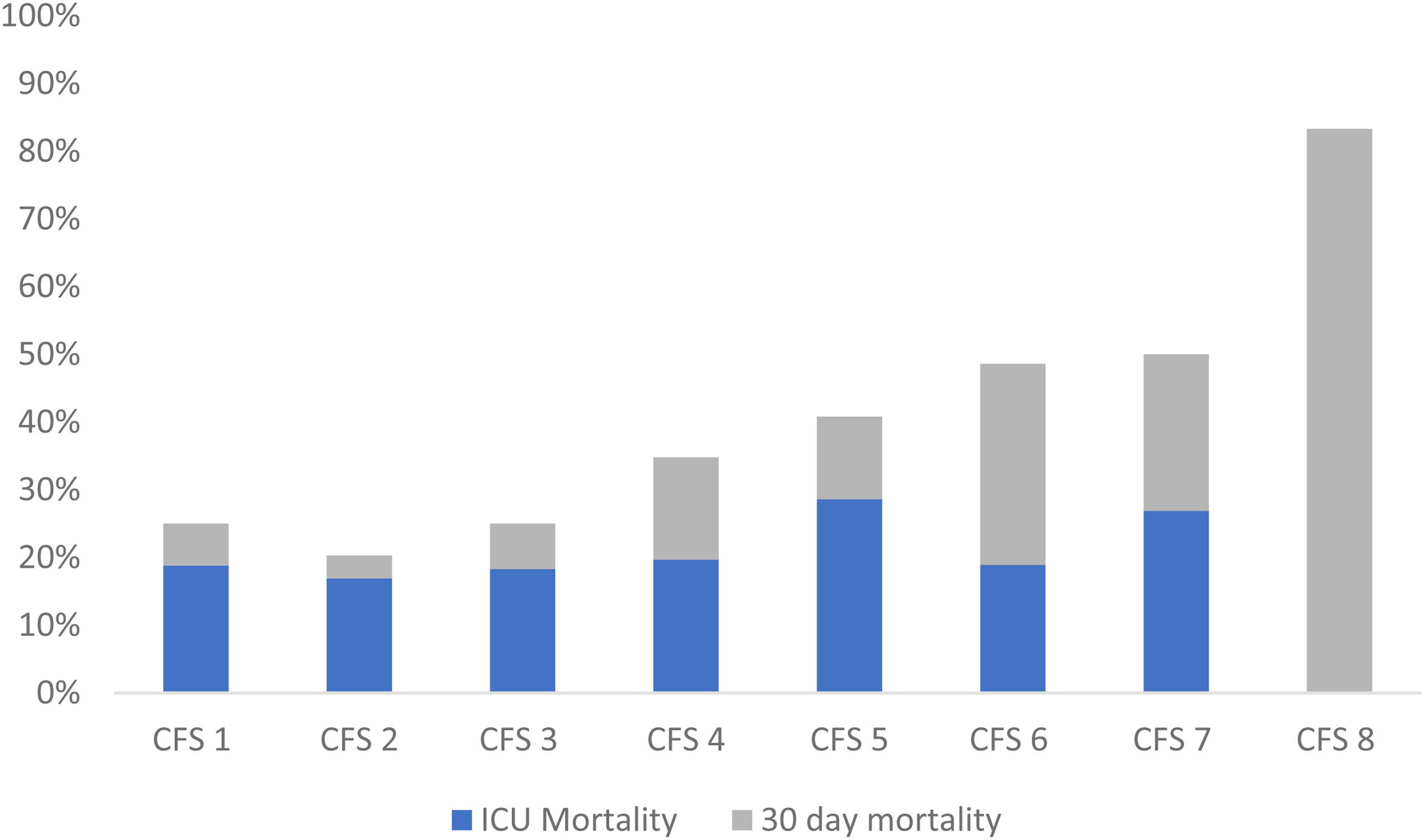

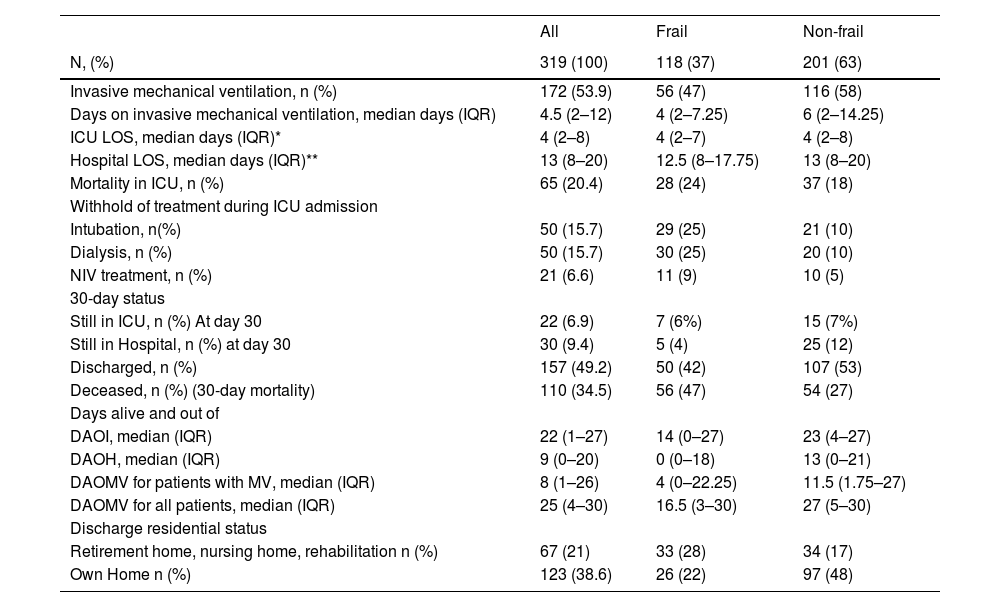

The overall ICU mortality rate was 20.4% (n = 65), and the 30-day mortality rate was 34.5% (n = 110). The mortality was higher among the frail patients, ICU mortality of 24% (n = 28) versus 18% (n = 37), and 30-day mortality of 47% (n = 56) versus 27% (n = 54) (Table 2). The 30-day mortality increased with higher CFS score, whereas the ICU mortality did not demonstrate a similar relationship (Fig. 2). When each CPS category separated ICU and 30-day mortality rates, no clear pattern was observed (ESM S4).

Outcome data.

| All | Frail | Non-frail | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N, (%) | 319 (100) | 118 (37) | 201 (63) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 172 (53.9) | 56 (47) | 116 (58) |

| Days on invasive mechanical ventilation, median days (IQR) | 4.5 (2–12) | 4 (2–7.25) | 6 (2–14.25) |

| ICU LOS, median days (IQR)* | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–8) |

| Hospital LOS, median days (IQR)** | 13 (8–20) | 12.5 (8–17.75) | 13 (8–20) |

| Mortality in ICU, n (%) | 65 (20.4) | 28 (24) | 37 (18) |

| Withhold of treatment during ICU admission | |||

| Intubation, n(%) | 50 (15.7) | 29 (25) | 21 (10) |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 50 (15.7) | 30 (25) | 20 (10) |

| NIV treatment, n (%) | 21 (6.6) | 11 (9) | 10 (5) |

| 30-day status | |||

| Still in ICU, n (%) At day 30 | 22 (6.9) | 7 (6%) | 15 (7%) |

| Still in Hospital, n (%) at day 30 | 30 (9.4) | 5 (4) | 25 (12) |

| Discharged, n (%) | 157 (49.2) | 50 (42) | 107 (53) |

| Deceased, n (%) (30-day mortality) | 110 (34.5) | 56 (47) | 54 (27) |

| Days alive and out of | |||

| DAOI, median (IQR) | 22 (1–27) | 14 (0–27) | 23 (4–27) |

| DAOH, median (IQR) | 9 (0–20) | 0 (0–18) | 13 (0–21) |

| DAOMV for patients with MV, median (IQR) | 8 (1–26) | 4 (0–22.25) | 11.5 (1.75–27) |

| DAOMV for all patients, median (IQR) | 25 (4–30) | 16.5 (3–30) | 27 (5–30) |

| Discharge residential status | |||

| Retirement home, nursing home, rehabilitation n (%) | 67 (21) | 33 (28) | 34 (17) |

| Own Home n (%) | 123 (38.6) | 26 (22) | 97 (48) |

Outcome data for all patients according to frailty (CFS ≥ 5) and non-frailty (CFS < 5).

NIV: non-Invasive Ventilation, DAOI: Days Alive and Out of ICU, DAOH: Days Alive and Out of Hospital, DAOMV: Days Alive and Out of Mechanical Ventilation.

The discriminatory ability of CFS as a categorical variable in predicting 30-day mortality was associated with an unadjusted AUC of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.59 to 0.71), increasing to an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.83) after adjusting for confounders. The discriminatory ability of CPS in predicting 30-day mortality was associated with an unadjusted AUC of 0.55 (95% CI, 0.48 to 0.61), increasing to 0.75 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.81) after adjusting for confounders. Combining CPS and CFS, the discriminatory ability in predicting 30-day mortality was associated with an unadjusted AUC of 0.66 (95% CI, 0.60 to 0.72), which increased to an adjusted AUC of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.81). The adjusted discriminatory ability of CFS, dichotomised as non-frail/frail, in predicting 30-day mortality had an AUC of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.82) (Fig. 3, ESM S5).

The calibration performance plot for the four adjusted models showed excellent calibration, with intercepts of 0.00 and slopes of 1.0. The accuracy of the prediction, evaluated by the Brier score, was moderate, with a score of approximately 0.20 for all models (ESM S6).

Subgroup analyses by age (65 vs. ≥65 years), and admission type (medical vs. surgical) showed excellent model performance in patients under 65 years, and in those with surgical admissions, with AUC 0.84 (95% CI, 0.75 to 0.94) and 0.81 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.9), respectively, but accuracy was lower in these subgroups. In contrast, model performance in patients aged 65 years and above, as well as those with medical admissions, was comparable to that observed in the total study population (ESM, S12).

Approximately 54% (n = 172) of the patients received invasive mechanical ventilation. For the frail patients, a lower proportion was observed compared to the non-frail, 47% versus 58%, and a shorter median time on the ventilator was noted, 4 days (IQR 2–7) versus 6 days (IQR 2–14) (Table 2, ESM S7). There was, though, no association between CFS and days with invasive ventilation (ESM S9). When converting the measure of mechanical ventilation to DAOMV, the median days were 4 days (IQR 0–22.25) and 11.5 days (IQR 1.75–27) for frail and non-frail patients, respectively, and the association between CFS and DAOMV became statistically significant (p = 0.026) (Table 2, Fig. 4, ESM S9).

The ICU LOS for frail and non-frail patients was equal, and no statistically significant association was found between CFS and ICU LOS (Table 2, ESM S8–S9), but the associated measure DAOI showed a statistically significant association with CFS (p = 0.038) (Table 2, Fig. 4, ESM S9). The association between CFS and DAOH as a composite measure of Hospital LOS was not statistically significant (p = 0.09) (Table 2, Fig. 4, ESM S8–S9).

A higher proportion of frail patients experienced withholding of life-sustaining treatments during ICU admission compared to non-frail patients: intubation (25% versus 10%), dialysis (25% versus 10%), or NIV (9% versus 5%) (Table 2). Higher CFS levels were consistently associated with withholding of life-sustaining treatment across all three treatment categories: invasive mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and NIV (ESM S11). Among the frail patients with pre-ICU-admission limitations, 30-day mortality was 58.6 % compared to 43.8 % in those without limitations. Overall, 30-day mortality was approximately doubled in patients, regardless of frailty status, who experienced any treatment limitation, either pre-ICU or during ICU admission, compared to those without limitations. Notably, among patients with any treatment limitation, mortality was similar between frail and non-frail patients (60%) (ESM S13).

In contrast to 90% of the patients who lived at home prior to admission, only 38.6% of the patients were registered as being discharged to their own homes. We had, though, a large proportion of the patients dying (34.5 %), and approximately 24 % were still admitted to the hospital (Tables 1 and 2, ESM S10).

DiscussionIn this study, we investigated the prediction of 30-day all-cause mortality by frailty and comorbidity in a mixed ICU population. We found an acceptable discrimination for the CFS predicting 30-day mortality, and the model fitted well. Adding the CPS did not improve the model's predictive performance. Moreover, the CFS was successfully implemented, with 79% of the scores being performed by clinicians, and the ratings remained stable throughout the year. From our perspective, this demonstrates the clinical applicability of the CFS.

Several previous studies have identified pre-admission frailty as an independent predictor of 30-day mortality among older ICU patients across a broader case-mix. Moreover, combining the CFS with SAPS3 or the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) has been shown to improve the prediction of 30-day mortality, suggesting the importance of also accounting for acute illness. 4,5,17 Our analysis suggested a possible element of self-fulfilling prophecy among the most frail patients. This is supported by the observed association with pre-ICU decisions to withhold life-sustaining treatment, indicating that the therapy may have been adapted prior to ICU admission in response to the patient's individual preferences and physician perceptions of the patient's physiological reserve (ESM S11). Treatment adaptation may also occur during ICU admission, but is likely driven by the patient’s response to critical illness and the effectiveness of ICU treatments. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which reported similar rates of pre-ICU limitations, approximately 30% among frail patients, comparable to those observed in our study (Table 1).4,5

Okahara et al. analysed the association between frailty and the duration of mechanical ventilation in an ICU population and found that frail patients, especially younger ones, received mechanical ventilation for a more extended period than non-frail patients.18 In contrast, a meta-analysis by Muscedere et al. found no significant difference between frail and non-frail patients in either the use or duration of mechanical ventilation.19 In our cohort, fewer frail patients received invasive mechanical ventilation and those who did had shorter treatment durations (mean 6 days vs. 4 days). However, consistent with the findings of Muscedere et al., we found no statistically significant association between frailty and length of mechanical ventilation (ESM S9). Notably, when we transformed the outcome into the composite measure of DAOMV, a significant association with frailty status emerged. This suggests that DAOMV may offer a more meaningful assessment by accounting for mortality.20

We found no significant association between CFS and ICU LOS or hospital LOS. However, following transformation of the outcome into DAOI and DOAH, we were able to better account for the fact that the sickest patients, often those who are frail, may die early during their ICU stay, resulting in shorter LOS without recovery (ESM S9). Similarly, Muscedere et al. reported no statistically significant difference in LOS between frail and non-frail patients, although they did not examine any composite outcomes related to LOS.19

Previous studies have found that prolonged hospitalisation is an indicator of frailty.21 In our study, we demonstrated a decline in the percentage of patients living at home across all CFS levels, from 90% to 38% (Tables 1 and 2). These results are challenged by mortality and the proportion of patients still being admitted to the hospital at the end of the 30-day follow-up period. Moreover, we did not investigate whether patients were admitted to temporary rehabilitation or permanent nursing homes. Previous studies have primarily investigated activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life (QoL) in frail participants after ICU admission and found a decline in both after discharge from the hospital.22 Few studies have data on living arrangements before and after ICU admissions, but Wozniak et al. did find that frail patients are more likely to require nursing assistance at home compared to non-frail patients.22

Although other commonly used scoring systems like e.g., the Charlson Comorbidity Score (CCS) could have been considered as a measure of comorbidity, we chose to apply the CPS in our study. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between CPS and mortality in older trauma and burn patients.9,11,18 The CPS incorporates the severity of chronic illness by combining different diagnoses with the number of medications necessary for treatment.9,23,24 Until recently, the CPS had not been applied to an ICU population. Guidet et al. investigated the association between functional status, comorbidities, and mortality in elderly ICU participants as part of the VIP2 study, but did not find the CPS predictive of mortality in that population.5 Notably, there is a substantial difference in median CPS values between the two populations, median 10 (range 7–14) in VIP2 vs. 13 (range 7−18) in our study. The reason for this discrepancy is not apparent. Participants in the VIP2 study had a median age of 84 year (range ≥ 80), compared to a median age of 69 years (range ≥ 40) in our study. Additionally, 72.8% of VIP2 participants lived at home, compared to 90% in our cohort. Despite these differences, the median pre-admission CFS score was 4 in both populations (Table 1). An older population may be admitted to the ICU according to more selective criteria, resulting in a relatively healthier subset of the elderly population. In contrast, younger ICU patients may include individuals with a greater comorbidity burden.5 By applying the CPS to a broader ICU population, our study contributes to the emerging focus on its utility in critical care settings.

In our study, we found a moderate correlation between CFS and CPS scores, suggesting multicollinearity between the two predictors. This may indicate that incorporating both variables into the model will provide less additional benefit compared to mutually independent variables.25 Our findings on CPS data suggest that the number of medical prescriptions mostly drives the correlation between CPS and CFS, as the median number of comorbidities for frail and non-frail patients was almost the same. Additionally, this suggests that CPS is a more informative measure than comorbidities alone.

The strength of this study lies in its inclusion of a broad spectrum of ICU patients, characterised by a high degree of data completeness. The prospective method reduces the risk of bias. The CFS was primarily performed by the clinicians after receiving thorough instructions, which gives the study generalisability. The inter-rater variability was reduced by having the same investigator (SW) to obtain all the CPS scores.

The study had several limitations. First, it is a single-center study with a relatively small population, which may challenge generalisability. Secondly, we have some incomplete data on ICU LOS and hospital LOS due to patients not yet being discharged at the end of the follow-up period, which may influence our secondary outcome analyses. The outcomes DAOI and DAOH, to some extent, compensate for this by combining LOS and mortality. A longer follow-up might provide valid information about the patients' destiny. We chose to exclude patients with an ICU stay <24 h, including those who died within the first 24 h. This decision was made to ensure that the attending physicians had sufficient time to perform a reliable estimation of the CFS. Additionally, in cases where the patient died within 24 h, the outcome “deceased” would already be known at the time of CFS estimation, introducing a potential source of bias. We acknowledge that this exclusion criterion may limit the external validity of our findings, particularly regarding acutely ill patients.

The CFS has only been formally validated in populations aged 65 years and older, despite several studies having applied it to younger cohorts aged 40 and above.22,26,27 Based on this, we chose to investigate the predictive value of frailty for mortality in our study population aged 40 years and above. Our age-stratified subgroup analysis showed that the predictive performance of the CFS for 30-day mortality in individuals under 65 years was at least comparable to that in those aged 65 years and older (ESM S12).

Finally, since the CPS did not improve the predictive performance model, we did not create a calibration model for the CPS, as we deemed this effort to be irrelevant.

The limitations of our study challenge the generalisability and the external validity of the results. Therefore, an external validation study would be necessary to discuss the relevance of the CFS instrument in the ICU setting. Future studies should aim to validate the CFS in populations below 65 years of age, and in more specific populations.

ConclusionsIn this study, we found that the CFS independently predicted 30-day mortality after ICU admission. Thus, frailty can be acknowledged as an independent predictor for short-term outcomes after ICU admission in a mixed ICU population. The discriminatory ability for predicting 30-day mortality was not improved by combining CFS and CPS compared to CFS alone.

Furthermore, we showed that the clinical implementation of the CFS can be performed effectively. We believe our study demonstrates that the CFS is providing clinicians with an additional tool to support decision-making.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors have contributed to the protocol of the study. MM, AF and SK have contributed substantially to the statistical analysis section and MM has performed the AUROC analysis. SW, LMP, CMB and OM have written the main text in the article. All authors have contributed to changes in the article and have approved the submitted version.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processThere has been no use of AI.

FundingNone.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ulf Gøttrup Pedersen.